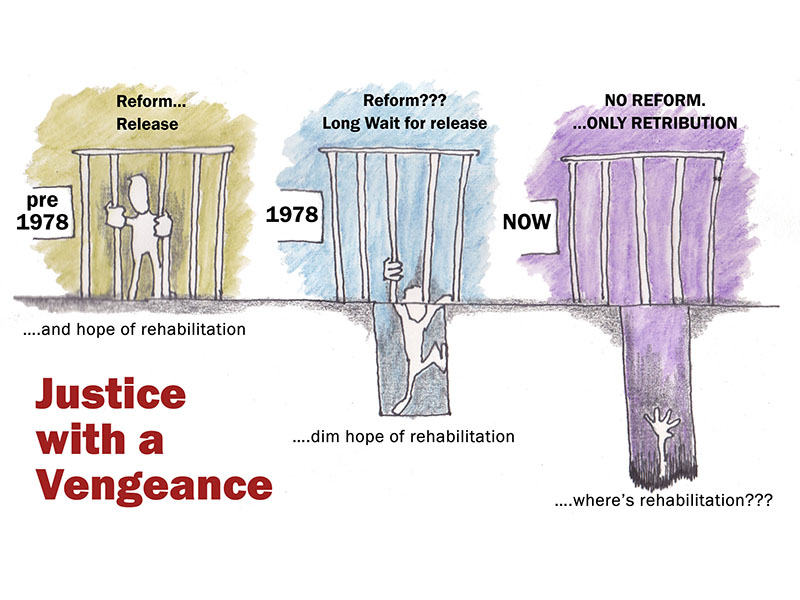

It was the ‘democratic’ post-emergency Janata Party government which started the trend of long prison sentences that continues to this day. Writes Arun Ferreira and Vernon Gonsalves.

June-July is the season for Emergency Politics in India. At this time every year, around the anniversary of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency proclamation of 25th June 1975, politicos of various shades and persuasions get down to the business of pontificating in defence of democracy. With the 2019 elections in sight, this year’s rhetoric was a tad louder.

The idiom and imagery however was tiringly repetitive. The Prime Minister and his party called the Emergency a Black Day and the Vice President’s speech was about the Darkest Hour; Congress and others referred to today’s Creeping Emergency and Undeclared Emergency. All the rulers wanted all the people to be Eternally Vigilant. Earlier years too had heard the same language.

There are many however who see both sides of this democracy debate as being similarly autocratic. The annual spectacle is particularly irksome for certain sections – such as those under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) – who do not see the 19 month Emergency as a period particularly more repressive than other times. Prisons are another area where lived experiences do not seem to have followed the accepted narrative of a despotic Emergency rule, followed by a post-Emergency democratic upsurge.

Anti-emergency ‘freedom-fighters’ did not fight for prison reform.

During the Emergency, 1,10,806 opponents of the ruling regime were detained – a figure that had amounted to almost one-third of the prison population. One would expect that this flood of political prisoners – recently designated as ‘freedom-fighters’ by BJP-ruled states – would have fought to change the prison system from within and, after coming out, when they ran the government, would have used their prison experience to implement policies and bring legislation that would transform the criminal justice system as a whole.

Source: Frontline

It looks like this did not happen. The state of India’s prisons continues to be as dismal as it was in 1975. Over forty years later, the Supreme Court is currently hearing a petition ‘Re: Inhuman conditions in 1382 prisons’, referred to it by R.C. Lahoti J, former Chief Justice of India.

Improvement in prison conditions in India have normally been the result of struggle by the prisoners themselves. Arun Jaitley, who wrote three blog posts to mark this year’s Emergency anniversary, relates how the Emergency political detenus managed to increase their monthly food allowance from rupees three to rupees five “after months of agitation”. (This however was a struggle by the MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act) detenus alone for an improvement in their own, already preferential, conditions. It did not involve the other prisoners and did nothing to improve their lot).

The better prison conditions in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh are the result of several struggles there of all the prisoners in the prisons, led by Naxalite political prisoners. Arun Ferreira, a co-author of this piece, has observed in his thesis that political prisoners are considered to be the potential leaders of any prison struggle.

However, despite most of those incarcerated being followers of Jai Prakash Narayan’s call for Sampoorna Kranti, they do not seem to have attempted any total revolution behind bars. Some like Kuldip Nayar have written of the slave like exploitation of young boys in jail and about other evils, but there is hardly any record of the Emergency detenus attempting to put a stop to such abuse.

In fact, there were very few attempts by the Emergency political prisoners to fraternize with the ordinary prisoners. Diaries and writings by detenus like LK Advani and Jaitley tell stories of the deep discussions and interactions among them, but not much is said about what was shared with the ordinary prisoner.

Counter-narrative of a Naxalite’s Prison Diary

One can have a glimpse of the view from the side of an ordinary prisoner from a book recently released in English –13 Years – A Naxalite’s Prison Diary (1970-83) by Ramchandra Singh. He was a Naxalite political prisoner from a poor ‘backward’ arak caste background, who was incarcerated in five different jails of Uttar Pradesh.

His prison period spans the events of the Emergency mass detentions and the major human rights initiatives of the post-Emergency activist Supreme Court around the turn of the eighties. His version is however something of a counter narrative.

The ‘freedom-fighters’ against Emergency would only agitate for their own demands within the prison, while remaining aloof from the average prisoner. The crafty prison officials would be wary of directly using strong arm tactics against these political detenus, who could very well come back into government. They would therefore use the other prisoners to torment them and even beat them up under the guise of intra-prison conflicts. The politicians were most often unable or more likely unwilling to bridge this divide with ordinary prisoners.

Almost seven years of Ramchandra Singh’s period in prison was in the post-emergency period, when, according to accepted wisdom, there was an improvement in the country’s human rights situation brought about by the sundry battles waged by democratic rights and civil liberties organizations that sprung up as a response to the horrors of the emergency. It was also the period when the Supreme Court introduced the concept of Public Interest Litigation (PIL) and brought many judgments to improve conditions for prisoners.

Ramchandra’s narrative however shows how nothing much changed within prison walls and efforts of the human rights movement and initiatives of the Supreme Court had little or no impact on the actual conditions of those behind bars. Despite almost the whole cabinet of the post-emergency Janata regime being composed of ministers who had been detained during the emergency, the government did not take any significant steps to make the criminal justice system more progressive. In fact the Janata rule brought a sharp turn away from reformative justice to retributive justice.

Section 433A and the shift towards longer prison sentences

The impact of one such major regressive step of the Janata government is discussed in some detail by Ramchandra’s book. In December 1978, the Central government introduced a new Section 433A in the Criminal Procedure Code making it mandatory for a life convict to undergo a minimum of fourteen years in prison before being eligible for premature release. This was much higher than the period of imprisonment then considered by many states to be necessary to reform a convict prisoner.

Ramchandra Singh relates that, in UP, there was a provision for release on probation after five years, though this was rarely implemented. It was however common to be released within eight to ten years for good behavior. In Punjab, a policy decision in 1971 had issued instructions providing that a period of actual sentence of eight and half years in the case of adult male prisoners undergoing life imprisonment and six years in the case of female prisoners was sufficient for evaluating whether a prisoner had reformed and could be prematurely released.

Source: scroll.in

It is a common belief in jails to this day that the 433A amendment was the vicious revenge of the Janata Party ministers who had faced harassment from convict prisoners in jail during the emergency. We, the co-authors of this piece, were told this almost thirty years later, when we were jailed. Whatever be the motivation, this step definitely showed drastic reduction in faith in the process of prisoner reform. It turned the clock back towards retributive justice.

Ramchandra describes the horror of lifer prisoners like him when the news of the new amendment reached them. A long battle ensued with work stoppages, hunger strikes and other struggles in various prisons and petitions in the courts. Finally the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the new statute.

All retribution and no reform

The years after Ramchandra’s release have only seen a further slide away from the reformative and rehabilitative approach to crime and punishment. The shift started by the post-Emergency Janata government has continued.

Cosmetic alterations abound, like changing the name of jails to reformatories and even correctional homes. All prison gates in Maharashtra proudly sport the motto ‘Sudhaarnaaaani Punarvasan’ (Reform and Rehabilitation). Actual government policy however shows a deep unwillingness of the state to actually implement this prison motto.

The guidelines in Maharashtra for premature release of lifers have seen a sharp increase in the years of imprisonment required to evaluate whether a convict has reformed. The first circular issued in 1978 after the introduction of Section 433A prescribed periods ranging from 16 years to 24 years, depending on the crime. The next circular in 1992 sharply raised this to a range from 22 years to 30 years. In 2010, a circular raised the upper end of the range, in cases under special ‘stringent’ laws, to 60 years.

Such steady and steep increases in the prison periods reflect the deepening distrust of the government in the very possibility of reform; its obverse is the vanishing hope of the prisoner in the likelihood of rehabilitation.

(Representative image) Mumbai’s Byculla jail women prisons launched major protests against cruelty and inhuman conditions in jail, in June 2017. Source: The Wire

The background to this is the attitude of most politicians and large sections of the media which project harsher retribution as a quick-fix answer to any crime.

When a celebrity like Sanjay Dutt or Salman Khan is convicted, the focus of media discussion is on the need for greater punishment. Politicians promise harsher punishments, even for juveniles, every time there is a mass upheaval against a horrendous crime. The recent Ordinance prescribing death sentence for child rape is an example of this type. This is despite there being ample proof that there is hardly any deterrent effect of increasing the punishment.

Courts too have been increasingly playing to this rabid gallery by developing a theory of collective conscience, which often means sentencing by media. Along with an increase in death sentences, the courts have, where the death sentence is removed, increasingly ordered imprisonment for the whole natural life. This practice denies any possibility of reformation and has been called a ‘hidden death penalty‘.

After a long gap of Presidents who were reluctant to reject mercy petitions of convicts on death row, the last President rejected a total of thirty mercy petitions. President Ramnath Kovind has already rejected the first mercy petition of a death row prisoner that came before him.

Ramchandra Singh is however not around to see this. He died on 2nd March, 2018.

Illustrations: Arun Ferreira