A new choreography by a Chennai-based dancer speaks of caste-oppression and honour killing in Tamil Nadu, addressing the contemporary socio-political issue in a straightforward manner. How severe is the truth underlying the content of this work?

Madhushree

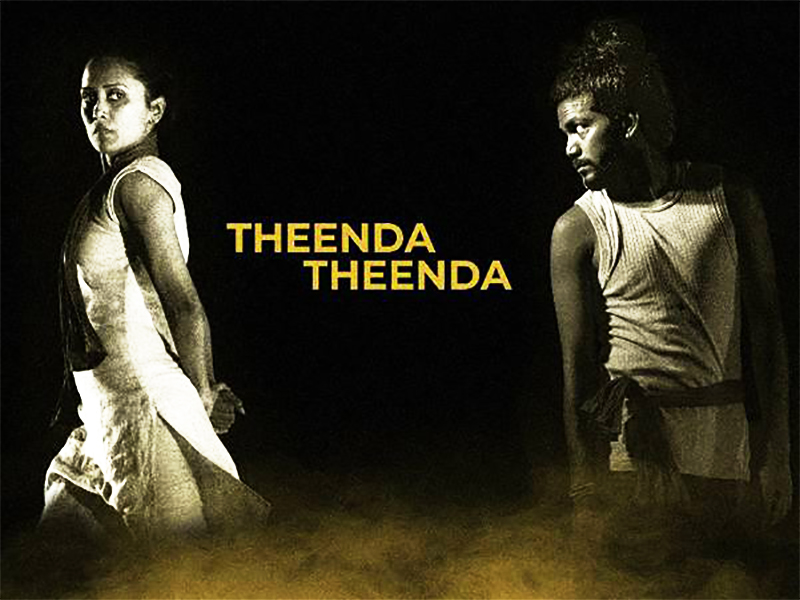

Teenda Teenda

In travel advertisements, the image of Indian culture is often represented by a smiling Bharatanatyam dancer, to be immediately associated with Tamil Nadu. Even otherwise, for those who do not look at dance as an exotic entertainment practice of dressed-up painted women, or those who are actually interested in the history and science of dance in India, Tamil Nadu – in particular Chennai – has been an important space to explore. Not just as a hub of Bharatanatyam and other South Indian classical and folk dance forms, but as a city that hosted some of the pioneers of Indian contemporary dance, and has been hosting practitioners and researchers who have influenced Indian contemporary dance in definitive and progressive-liberal ways.

Chennai-based contemporary dancer Akila’s new choreographic work Teenda Teenda (தீண்டத் தீண்ட: As We Touch… or As We Get Close By…) falls in the same legacy. It is Akila’s first full-length choreography, though she has created smaller works earlier in her 12 years long training and engagement with contemporary dance and various other forms of movement and music for many more years. The work is a straightforward statement in dance, critiquing caste dominance and the many facets of its atrocities with the focus on inter-caste honour killing that plagues Tamil Nadu till date. Minimal in its composition and choreography, Teenda Teenda is an almost entirely non-verbal play between two bodies, performed by Akila and contemporary dancer/movement-practitioner Chandiran, “finding a balance between abstraction and narration, not reflecting the content through the body, but within the body.” – explains the Tamilian choreographer. The movements in this work stem from wanting to identify the body-language of social hierarchy – violence, pain, arrogance, submission, dissent and such like, exploring “how the caste-violence affects the personal space of an individual who attempt to resist with an aspiration of equality” in particular.

Unlike the cheerful image of a stereotyped Bharatanatyam dancer, Indian contemporary dance has not found a place of honour in travel advertisements sponsored by the government or the corporate, which is just as well.  However, even if it does find a place, Akila’s work is less likely to be there, especially since the state government of Tamil Nadu is in vehement denial of the existence of honour killing, just as it denies or diminishes the dimensions of other caste-related atrocities prevalent in the state such as mistreatment of denotified tribes, untouchability etc.

However, even if it does find a place, Akila’s work is less likely to be there, especially since the state government of Tamil Nadu is in vehement denial of the existence of honour killing, just as it denies or diminishes the dimensions of other caste-related atrocities prevalent in the state such as mistreatment of denotified tribes, untouchability etc.

Teenda Teenda consists of two short solo sections followed by a longer duet, loosely weaving a narrative pattern. It ends on a simultaneously hopeful and grim note: the dance speaks of dissent and a prospective interlocking of caste identities as a means to that, but at the same time, the lights go dim over a repetitive ritual of movements symbolizing the endless saga of honour killing. The solos are played first by Akila as an upper caste character – bold and arrogant in her fair costume, and later by Chandiran as the lower caste one – grey and subdued. Their differently coloured sashes are cleverly used to symbolize the different caste identities (not specific ones) in various ways – sometimes boasting the dominating power of a character, sometimes restricting and stunting another, some other times entangling with one another to symbolize the above-mentioned interlocking – an aspired unity between the castes. The deliberate choice of the woman performer playing the oppressor and the man as the victim is a political statement in itself that can be looked at in several ways. In this case, Akila explains, the choice stemmed from the fact that in most of the cases of honour killing, the ’condemned’ relationship is between an upper caste woman and a man from a lower caste.

The entire work is accompanied with various rural percussions from Tamil Nadu and Kerala: Urumi, Thudumbu, Thappu, Tavil, Edakka, Kanjira, Udukkai and Makudam – a somewhat rare choice for a contemporary dance piece in India. Not just the content or the specific choice of Tamil bodies and their movements, but it is also the use of these instruments that curiously transforms the silence within the bodies into a very Tamil silence. As a non-Tamil audience of this work, it makes me wonder whether this work especially calls for an audience with a pre-knowledge as well as a deep sense of socio-cultural-political solidarity with the Tamil self-respect movement. If yes, does that make the work limited in some way, or does it welcome me – an audience – to extend my understanding beyond certain limitations of my own, in another way? There is surely food for thought in this direction in the context of any kind of cultural practice – especially in this era of fundamentalist cultural appropriation and attempt of domination of certain languages over the others.

The politics of the work: the politics of silence

There have not been significantly enough attempts to directly take up contemporary political subjects in the field of Indian dance – classical and contemporary alike. In the narrative-heavy classical case, the lack of politically powerful content is unfortunate, but perhaps not so surprising, given the un-evolving regressive nature of classical dance pedagogy and practice, with rare exceptions. In the contemporary case it is more surprising, given how it has thrived in an ambience of political progressiveness. The reason in this case partially lies in its politics of de-association from the very narrative nature of classical dance – initially based on the affinity of these narratives with Hindu religiosity and an objectified, limited perspective on femininity. However, the process of de-association did not end there, rather continued, creating a seemingly permanent disengagement between the abstract nature of contemporary dance and popular understanding, acceptance and identification, hence appreciation.

In that respect, Akila’s Teena Teenda is an interesting exception. Although the movements in the dance are theatrically inspired and not entirely free of narrative characteristics, the non-verbal nature and the preoccupation with details of the quality of movements, rhythm and finding the interrelation of the bodies and the space makes it a closer ally of dance than theater. However, more importantly than whether it should be labeled as dance or theater, what matters is how it affects the audience emotionally. And the affect depends as heavily on the skill of the choreographer/performer as the relation between the substance of the work and its audience. How has the reaction of the audience been so far? There have been two shows of this work. The first, taking place in a suburban college among Tamil youth coming from a widely varying range of castes (a large number of OBC, SC and Dalits among them, for whom honour killing is a more tangible reality than for the city-dwellers), the questions and reactions were based on the content, which might have been understood at a deeper personal level. The second show took place in Chennai to an audience primarily consisting of a mixed bag of Tamil and non-Tamil urban English-speaking artists. Here, the questions and reactions lacked immediate conviction, understanding or interest in the content, and the critique latched onto the abstract process and qualities of the movements and the choreography, which are still raw and vulnerable in this work – being in its germinating phase. Being present in both these shows, it seems to me, Akila – as a choreographer and a political being – may need to go a long way in truly understanding and being understood by her own audience, or in other words, in creating a middle-ground of understanding for the different audiences she seems to be dealing with, before her choice of bringing narrative content back to contemporary dance in Chennai finds a clear headway.

The second show took place in Chennai to an audience primarily consisting of a mixed bag of Tamil and non-Tamil urban English-speaking artists. Here, the questions and reactions lacked immediate conviction, understanding or interest in the content, and the critique latched onto the abstract process and qualities of the movements and the choreography, which are still raw and vulnerable in this work – being in its germinating phase. Being present in both these shows, it seems to me, Akila – as a choreographer and a political being – may need to go a long way in truly understanding and being understood by her own audience, or in other words, in creating a middle-ground of understanding for the different audiences she seems to be dealing with, before her choice of bringing narrative content back to contemporary dance in Chennai finds a clear headway.

The non-verbal nature of this work has a complex politics of its own. On one hand, as Akila and Chandiran point out in their dance, body-language has an important role to play in the context of caste oppression, which has a curiously silent nature. The lower caste people, in not being allowed to look into the eyes of the upper caste, lay their shadows on the road where the upper caste walks, desire the upper caste as partners, drink water from the same source as the upper caste does, cover their bodies as the upper caste does, touch anything or anyone that the upper caste ‘owns’ and in many such restrictions are constantly under a silent supervision within and without, lest their lower caste body resembles the upper caste body in movement or appearance. The surveillance is so overpowering that an option of a dialogue does not even arise. That is why, when in Teenda Teenda the dancers – constantly revolving in a circular path in diametrically opposite positions, symbolizing the circle of perpetuality of the horrific practice of honour killing – begin to acknowledge each other’s existence in space through eye-contact, it creates a subtle but magically emotive moment.

On the other hand, Akila’s choice of silence can also be read as a reaction to her own close but troubled and critical relationship with the overly vocal mainstream Dalit movement in Tamil Nadu suffering from identity politics and opportunism, lacking in thoughts regarding intersectionality (gender, class etc.) and the dire need of shaping the anti-caste movement outside the vote bank – or in other words, lacking in the broad vision of an inclusive, democratic, alternative movement. In Akila’s choice of silence lies the silencing of the most violently oppressed Dalit castes such as Pallar, Sakkiliyar, Vannaan, Thoatti, Arundadiyar and others, who are caught helplessly in the socio-political turmoil, facing the brunt of caste violence, losing on all opportunities.

Honour Killing in Tamil Nadu

Perhaps a peep into the depth of the issue of honour killing in Tamil Nadu brings more meanings to the shivers, falls and writhing that the dancers’ bodies attempt to go through. Akila chooses not to be too literal, or melodramatic about the horror underlying her content, but the knowledge of the horror adds meaning to this work and some of the specific choices she makes in executing it.

Honour killing is one of the many dirty facts that Swachh Bharat has consistently been in denial of. Tamil Nadu – a progressive state with above-average literacy rate and sex-ratio, bearing witness to one of the richest histories of caste movements in India – alone has seen 187 cases of brutal murders (with women as 80% of the victims) in the name of ‘caste honour’ in past 6 years. In general close to 500 lives – again, mostly women: ‘the flag-bearers of Indian honour’ – have been lost in honour killing all over India since 2014, the number rising steadily every year. Though Tamil Nadu has rarely seen honour killings based on religion unlike the rest of the country, inter-caste honour killing have been rampant as yet another manifestation of the general air of severe caste conflict, further fanned by right-wing forces ready to pounce upon the state that otherwise defended itself from their political-cultural penetration for a long time. The killings have involved a wide range of brutality such as hacking, poisoning, burning, chaining in public places, mass lynching and so on.

In general close to 500 lives – again, mostly women: ‘the flag-bearers of Indian honour’ – have been lost in honour killing all over India since 2014, the number rising steadily every year. Though Tamil Nadu has rarely seen honour killings based on religion unlike the rest of the country, inter-caste honour killing have been rampant as yet another manifestation of the general air of severe caste conflict, further fanned by right-wing forces ready to pounce upon the state that otherwise defended itself from their political-cultural penetration for a long time. The killings have involved a wide range of brutality such as hacking, poisoning, burning, chaining in public places, mass lynching and so on.

5 years ago, on the 4th of July, 19 years old Dalit youth named Ilavarasan’s body was found by a railway track in Dharmapuri in Tamil Nadu – reported as a suicide, but with all the evidences of being a homicide. He was married to Divya, who belonged to the Vanniyar caste, for eight months, during which they were repeatedly threatened by Divya’s family. Finally, Ilavarasan was arrested by police based on false cases and Divya was abducted by her own family, house-arrested and made to present false statements to the media. The incident – less ‘spectacular’ than some other cases of honour killing in Tamil Nadu – eventually disappeared from most of our minds as one of the many real-life horror stories that the society amply gifted us with. Yet, some of us remembered it well enough. The tragic incident came alive in an earlier version of Teenda Teenda, in the form of a dance-drama choreographed by Akila for the ‘Tirupattur Nataka Vizha’ under the conceptualization of Tamil writer Gnani. In its current stage, Akila sees Teenda Teenda as a more general statement of protest – less narrative, less emotional, more bent on a general note of dissent as well as of disillusionment with the patriarchy that weakens the anti-caste movement, as it has weakened many progressive movements, trickling from the very conservative forces that they struggled against. Can Teenda Teenda be called a constructive feminist cultural critique with a potential of emboldening the anti-caste movement? The answer can only be found in the future as to how the choreographer chooses, or is allowed the opportunities to proceed with it in that direction.

It has been popularly known and discussed in the context of socio-political role of dance, how Mrinalini Sarabhai’s 1963 choreography on dowry made Prime Minister Nehru set up a committee to resolve the issue of dowry deaths. In the case of honour killing, there is no special law in India to deal with it. There are certain collectives in Tamil Nadu working on this issue; ‘Evidence’ – working against all forms of caste discrimination – is one of the foremost. There have been other individual efforts to create awareness and help the prospective couples in danger (e.g. the ‘Kadhal Aran’ app). It is only towards the end of last year, finally, that an anti-honour killing board has been set in Madurai – first time in Tamil Nadu. Certain significant legal judgments have come across as positive measures, but despite all, so far, there has not been any significant change in situation. On the other hand, the law has been amply misappropriated by the killers in alleging rape and abduction against the bridegroom (e.g. in the case of Divya-Ilavarasan) by a surprisingly large number. It is undoubtedly high time that progressive artists, whose creative explorations and workshops can be of immense value in creating social awareness against this heinous practice, take this subject up as their content. In the particular context of Indian contemporary dance, works like Akila’s could be a welcoming and well-required beginning of a collaboration with social activism against honour killing and the anti-caste movement in Tamil Nadu in general. Although the artist herself is hesitant to identify her attitude towards her work as activism. She rather sees it as “creating new form for a contemporary content” – she explains – “Aim is to engage the contemporary social ideologies and realities within the contemporary dance space not as a propaganda but as a statement/opposition.” The ever-pending dialogue between artists and activists, also addressing questions around who is an artist and who is an activist, might have had something to add to this discussion.

Photography – Sreedhar