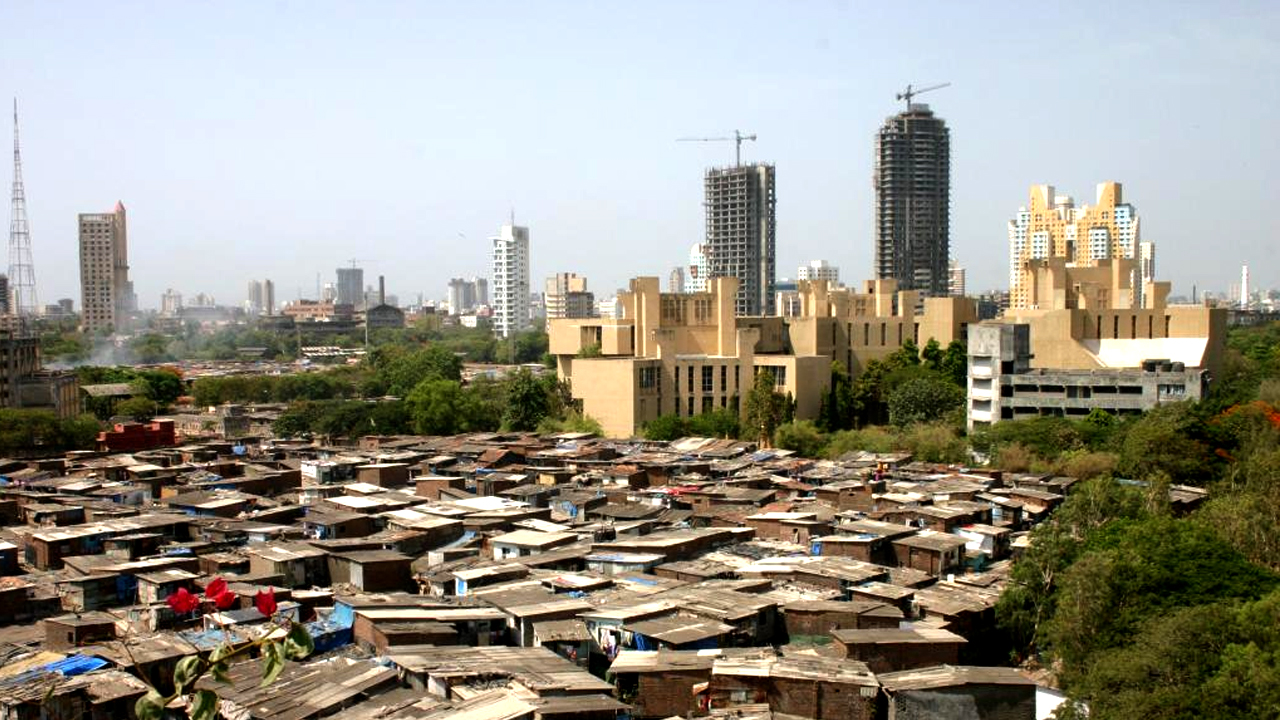

The World Inequality Report situates India as one of the world’s most unequal large economies with its world’s “fastest-growing economy” narrative standing in sharp contrast with an equally extreme concentration of income and wealth at the top.

Groundxero | 10 December 2025

The World Inequality Report 2026, released on Wednesday, brings out alarming statistics of the staggering and deepening economic inequalities shaping India and the world. The new report arrives at a moment when India’s “fastest-growing economy” narrative stands in sharp contrast with an equally extreme concentration of income and wealth at the top. The report’s findings reinforce what many economists have been repeatedly highlighting: India’s growth trajectory has been accompanied by an increasingly regressive distribution of income and wealth, marked by a sharp rise in top-end concentration and a simultaneous erosion of the middle strata.

The Inequality Report situates India as one of the world’s most unequal large economies, where the top 10 percent capture a staggering majority of national income and the top 1% command wealth on a scale that increasingly mirrors global plutocracy, while the bottom half of the population continues to receive only a marginal share of income and wealth even as their labour underpins the broader economy. Meanwhile, very low female labour-force participation (unchanged for a decade) suggests gender-based inequality continues to remain a major structural barrier.

Inequality in India — As per the Report:

- The top 10% earners in India capture 58% of national income.

- The bottom 50% in India gets only 15% of national income.

- The top 10% in India hold about 65% of national wealth.

- The top 1% in India holds about 40% of national wealth.

- Average annual income per capita (PPP) is 6,200 Euros

- Average wealth per capita (PPP) is 28,000 Euros

- Female labour participation rate is 15.7% (no improvement over past decade)

The report also notes a stark historical shift — in 1980 — a larger share of India’s population was in the “middle-40%” globally, but now “almost all” are in the bottom 50% globally.

Global Inequality — As per the Report:

- The top 10% of the global population earn 53% of global income.

- The bottom 50% of the global population receives only 8% of global income.

- In terms of wealth: the top 10% globally own 75% of all global wealth, while the bottom 50% own only 2%.

- The ultra-rich — the global top 001% (fewer than 60,000 people) — now hold three times more wealth than the poorest 50% of humanity combined.

India in Global Perspective

The Income inequality in India is worse than global average — top 10% in India take a bigger slice (58% vs. global 53%), even though bottom 50%’s share is higher than the global bottom (15% vs. 8%).

Wealth concentration globally remains more extreme — globally top 10% hold 75% while the bottom 50% own only 2% of wealth, but India still exhibits very high wealth inequality.

Globally the poorest half nearly have zero wealth share; in India the bottom half likely has somewhat more — but still unequal.

The existence of a global elite (top 0.001%) owning enormous wealth — in comparison to bottom half of humanity — places national-level inequalities like India’s in a broader picture of worldwide concentration of wealth.

However, the absolute living standards, per capita incomes/wealth in India are far lower than global averages, which means the bottom half in India — though getting 15% of income — may still live well below global median standards. The global numbers hide massive wealth disparities; so being “above global bottom” doesn’t guarantee reasonable living conditions.

Also, the “average per capita income/wealth (PPP)” figure of India doesn’t reflect median values — so real experience of a typical Indian may be much worse than these averages suggest. The gap between “average” per-person wealth/income and median or bottom incomes is likely to be significant because average wealth/income is pulled up by the wealthy minority.

The report highlights that inequality in India isn’t seen only in income or wealth — but also in gender (labour-force participation) and likely in access to social services, opportunities, etc. Very low female labour force participation (15.7%) suggests gender-based inequality remains a major structural barrier.

Conclusion:

The first and most striking fact emerging from the report is that inequality remains at very high levels. The concentration of wealth and income at the top is not only persistent, but it is also accelerating. Since the 1990s, the wealth of billionaires has grown at approximately 8% annually; nearly twice the rate of growth experienced by the bottom half of the population, indicating that the benefits of globalization and economic growth have flowed disproportionately to a small minority, while much of the world’s population still face difficulties in achieving stable livelihoods. These divides are not inevitable. They are the outcome of political and institutional choices.

In case of India, what emerges from the report is a structural picture rather than a conjunctural one. Despite economic growth, structural inequalities (income, wealth, gender participation) remain deeply entrenched. Also, the report indicates, over time, there is a marked shift toward greater income and wealth concentration at the top with a small elite (top 10%, and especially top 1%) controlling a disproportionately large share of both income and wealth.

The report invites a renewed interrogation of the institutional, fiscal, and policy choices that have shaped India’s post-liberalisation development model. It raises critical questions about India’s development model where resources extracted from labor and nature continues to sustain the prosperity and the unsustainable lifestyle of the few at the top. India’s GDP growth increasingly decoupled from broad-based social and economic well-being, raise urgent questions about policy measures directed towards redistribution of income and wealth through progressive taxation, strong social investment and fair labor standards to insure inclusive development.