Plestia Alaqad had just graduated when Israel launched its large-scale assault on Gaza on October 7, 2023. Within days, her city and her home were reduced to rubble. Amid bombings, displacement, and the relentless search for refuge, she continued to write. What she produced is far more than a chronicle of endurance under conditions of occupation and annihilation. It asks, with searing simplicity — What happens to being, to love, to meaning, when all is targeted for erasure?

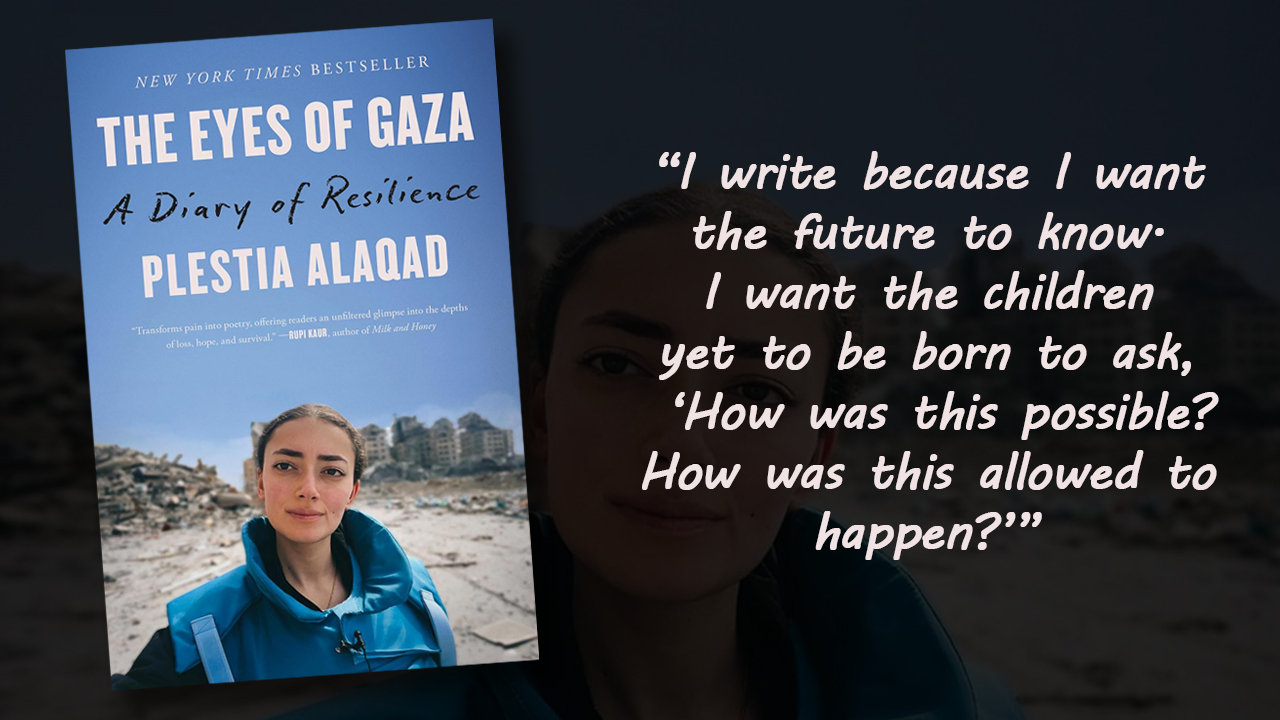

This review examines Alaqad’s The Eyes of Gaza: A Diary of Resilience as a work of testimonial and philosophical literature emerging during the ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza. Moving beyond conventional reportage, Alaqad’s diary redefines war writing as an act of ontological survival and ethical witnessing. Through an analysis of her narrative form, temporality, and political implications, this review situates The Eyes of Gaza within broader traditions of war diaries, existential philosophy, and anti-colonial resistance literature.

Arkadeep Goswami

Groundxero | Nov. 1, 2025

A Voice from the Rubble

War literature has long been the space where history breathes through human testimony. War diaries, especially, preserve what official records erase—the trembling, the mundane, the private rituals that make catastrophe survivable.

In The Eyes of Gaza, Plestia Alaqad, a young Palestinian journalist, writes a diary that refuses silence in the face of genocide and annihilation. Her words emerge not as distant reportage but as immediate cries — a living testimony from the ruins of Gaza.

Alaqad had just graduated when Israel’s massive assault began on October 7, 2023. Her home, her city, her world was reduced to dust and rubble before her eyes. Amid falling bombs and displacement, and the perpetual search for refuge, she continued to write—not as a reporter, but as a witness to the horrors of the genocidal assault on her people. She writes:

“I write because I want the future to know. I want the children yet to be born to ask, ‘How was this possible? How was this allowed to happen?’”

That question – how was this allowed to happen? – is not only directed at world leaders or systems of power. It pierces through the conscience of every reader who encounters her book. Her account in the book is not only a chronicle of survival—it is a philosophical meditation, a cry for justice, and a defiant act of remembrance.

The philosophical core of The Eyes of Gaza lies in its exploration of what might be called the crisis of being. Gaza, to Alaqad, is not merely a geographical entity but the condition of her being-in-the-world. The destruction of her home is thus not only a loss of property but an ontological rupture. When the physical world collapses, the life-world (Lebenswelt) disintegrates too.

The Crisis of Being amid Genocide

Alaqad writes of the small rituals that once composed her life: her favorite café, the rhythm of the sea, the laughter of neighbors. When these vanish, it is not just the space that is lost – it is the continuity of meaning itself. “When I came to Australia,” she recalls, “I realized how small Gaza is. I always knew it was 365 square kilometers, but I never understood what that meant.” The realization is metaphoric: to understand “how small Gaza is” is to feel the suffocation of an entire people, hemmed in by occupation and decades of blockade.

In philosophical terms, Alaqad’s diary becomes a testament to being-in-ruins. Yet amid the collapse, she clings to the act of witnessing. Writing becomes the ground of her existence, the thin line between nothingness and persistence. In naming faces, recounting stories, and preserving moments, she salvages fragments of the human world that Israel seeks to erase.

For the reader, this raises a haunting question: Can one preserve the self when the world that sustained it no longer exists? Alaqad’s answer is defiant – yes, through memory, through language, through testimony. Writing becomes her final shelter.

“To write is to remain. To name is to resist disappearance.”

Witnessing, Testimony, and the Ethics of Time

Every diary of war is, in essence, a document against time. It resists the erosion of memory, the dulling of outrage, and the amnesia that follows catastrophe. In The Eyes of Gaza, time fractures into three dimensions: the now of catastrophe, the past of the lost home, and the future of justice.

Alaqad writes for those who are not yet alive. She does not expect the present world to listen – indeed, she knows it has chosen not to. Her hope is that someday, the testimony of Gaza will be read in a time when humanity has regained its conscience. This gesture transforms her diary into what philosophers might call a temporal bridge – a writing that travels forward through time as an ethical message-in-a-bottle.

The book thus poses a profound question: what is our moral relationship to testimony? To read her words is to enter a contract with the dead and the displaced. To turn the page is to accept a burden: that of remembrance.

Alaqad’s act of writing is also a form of resistance to the politics of erasure. The modern world, saturated with images and reports, risks turning atrocity into spectacle. Her diary breaks that numbness. It speaks directly, without mediation, with the raw voice of someone who has lost everything yet refuses silence.

Ethics under Extremity: The Persistence of the Human

What does it mean to be ethical when the structures of morality collapse? Alaqad’s writing, without moralizing, answers this through lived moments. Amid airstrikes, displacement, and hunger, she observes small acts of kindness – the boy who tries to rescue his donkey, the family that shares a piece of bread, the laughter that breaks through the rubble.

Such moments, trivial at first glance, reveal the deepest layer of the book’s philosophy: that humanity, even when assaulted, resists extinction. Alaqad’s humour, tenderness, and honesty – her ability to feel beauty in the smallest things – stand as quiet refutations of dehumanization.

Ethically, The Eyes of Gaza demands that the reader refuse indifference. It breaks the comfortable divide between “observer” and “victim,” insisting that witnessing itself entails responsibility. Her writing refuses the neutrality of the global gaze. To be neutral in the face of genocide, she reminds us, is to be complicit.

Hope, Resilience, and the Future as Resistance

Perhaps the most astonishing quality of The Eyes of Gaza is that it is not only a book of despair. Amid the ruins, there is an unyielding hope – what one might call the metaphysics of resilience. Hope, here, is not naïve optimism. It is the act of continuing to breathe when breathing itself becomes an act of defiance.

Alaqad calls her book “a tribute to Gaza and its people.” This tribute is not sentimental – it is revolutionary. Through her words, the dead speak, the destroyed city lives again. She imagines a future where the world might understand, where Palestine is not a question of geopolitics but of humanity.

Philosophically, this hope emerges as a dialectic: destruction and creation, despair and affirmation. When every structure collapses, human beings reinvent meaning. The imagination of another world – amid the ashes of this one – becomes a form of spiritual and political struggle.

As she writes: “They destroy our homes, but we rebuild with memory. They erase our streets, but we remember the paths. They want to make us forget, but we remember everything.”

This act of remembering is political. It transforms mourning into rebellion. It asserts that history cannot be written solely by the victors.

The Politics of Narrative and the Struggle over Meaning

The Eyes of Gaza must also be read as a political text – because to write as a Palestinian is already a political act. Alaqad’s diary contests not only the current war but the entire historical structure of dispossession. “We say the Nakba happened in 1948,” she writes, “but in reality, it never stopped.”

That line encapsulates the political essence of her writing: the idea of ongoing catastrophe. It is a reminder that the violence of Gaza is not episodic but structural, part of a colonial continuum. Her diary dismantles the sanitized language of “conflict” and “casualty,” replacing it with the intimate language of lived suffering.

For readers engaged in questions of state power, secularism, or imperialism, the book serves as a living counter-narrative. It challenges the global discourse that normalizes Palestinian suffering as background noise to “security concerns.” By placing the human voice at the center, it reclaims narrative agency from media filters and political euphemisms.

The politics of her narrative also extend to the very form of the diary. The fragmentary, episodic entries mirror the fragmented reality of life under siege. The absence of linear structure becomes a political statement – the impossibility of coherence under conditions of collapse.

The Aesthetic of Raw Testimony

From a literary standpoint, The Eyes of Gaza is stark and immediate. Its aesthetic power lies in its refusal of artifice. There is no attempt at stylistic polish or rhetorical flourish. The prose is simple, direct, sometimes trembling. This rawness becomes its strength – it allows authenticity to shine through.

The diary form also allows Alaqad to capture temporality in flux. Each entry, dated and grounded in the moment, creates an intimate rhythm: the passing of days amid a world that no longer moves normally. This produces a strange tension between time and timelessness – each day feels both urgent and endless.

Her writing may remind us of one of other war diaries – Anne Frank’s, of course, but also the Bosnian writer Zlata Filipović, or the Syrian poet Samar Yazbek. Yet Alaqad’s voice is distinctly Palestinian: infused with generational trauma, yet also with humor, irony, and the stubborn joy of being alive.

Critiques and Limitations

Like all diaries, The Eyes of Gaza bears the strengths and limitations of its form. It is episodic, emotional, and necessarily subjective. Readers expecting a comprehensive historical or political analysis may find it lacking. But the book does not claim to provide a structural account of the conflict – it is, instead, a testimony from within it.

At times, the emotional intensity can be overwhelming. The reader may feel helpless, unable to process the sheer scale of suffering. But perhaps this discomfort is essential. To feel burdened by another’s pain is the beginning of ethical awakening.

One might also wish for a broader contextual framing – how Alaqad’s experiences fit into the larger historical narrative of Gaza’s struggle. Yet that omission, too, is instructive: it shows that for those living through catastrophe, survival precedes theory.

The diary’s strength, then, lies not in comprehensiveness but in presence. It does not explain Gaza – it is Gaza, a living organism, speaking.

Relevance in the Age of Digital Witnessing

In our hypermediated world, where images of suffering circulate endlessly, one might ask: why read a diary when the war itself is live-streamed? The answer lies in the difference between seeing and witnessing. To see is passive; to witness is transformative. Alaqad’s diary resists the desensitization that comes from constant exposure. Her words slow us down. They force us to inhabit the experience, not merely observe it. The text becomes a countermeasure to the digital age’s rapid forgetting. Moreover, in a time when information is weaponized, and truth itself is contested, The Eyes of Gaza becomes a moral archive. It is not just a record of what happened, but a safeguard against the denial that inevitably follows genocide.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, The Eyes of Gaza is not merely a war diary – it is a philosophical petition, a cry for the restoration of humanity. Alaqad’s voice, young yet ancient in its pain, cuts through political rhetoric and media fatigue. She does not ask for pity; she demands recognition.

To read this book is to be transformed, however slightly. One cannot finish it and return unchanged. But reading it asks of us – not just to know – but to act. To let the knowledge of suffering alter our sense of what justice, solidarity, and compassion mean in a world that has normalized cruelty. If one chooses a contemporary text to meditate upon the ethics of witness, the meaning of home, and the politics of memory in our age of mass violence, The Eyes of Gaza stands as a haunting companion.

________________

Arkadeep is a political activist and writer based in Kolkata.