What made The Squid Game Netflix’s most-watched series of 2021 was not just its visual panache, its excellent cast, its crackerjack script and the nail-biting suspense of its gladiatorial contests. Rather, the series was the first work of mainstream streaming media to openly identify the single most dangerous political movement of our time, namely plutofascism, writes Dennis Redmond.

Netflix’s blockbuster television series, The Squid Game, is not the first mass media work to enthrall viewers with the idea of a game show which is nothing but a gladiator pit.1 Yet what made The Squid Game Netflix’s most-watched series of 2021 was not just its visual panache, its excellent cast, its crackerjack script (written by Dong-hyuk Hwang, who also directed the series), and the nail-biting suspense of its gladiatorial contests. Rather, the series was the first work of mainstream streaming media to openly identify the single most dangerous political movement of our time, namely plutofascism.

To understand why this is so, it is worth defining just what plutofascism is and how it differs from its early 20th century forebears. Today’s plutofascism is the post-2008 fusion of thieving plutocracies with despotic autocracies. It is the alliance of billionaire edge-lords with millionaire crime-lords. Its goal is to enrich and empower three thousand billionaires and autocrats, by impoverishing and disenfranchising all 8 billion human beings who work for a living on our planet.

The nine most prominent examples of plutofascism include Brexitism in Britain, Bolsanaroism in Brazil, Xiism in China, Orbanism in Hungary, Modism in India, Duterteism in the Philippines, Putinism in Russia, Erdoganism in Turkey, and Trumpism in the United States. Every single one of these movements deeply damaged their respective societies, by concentrating wealth and power in the hands of the few at the expense of the many.

While today’s plutofascism has similarities to early 20th century fascism2, it also has one crucial difference. Whereas Italian, German and Japanese fascism sought to restore failed colonial empires by creating fake imperial races, early 21st century plutofascism seeks to restore failed neocolonial empires by creating fake imperial masculinities. What made The Squid Game captivating to hundreds of millions of viewers was that it showed how the swindle of imperial masculinity is knowingly perpetrated by plutofascist elites – and unknowingly perpetuated by plutofascism’s victims.

It is no accident that every single plutofascist regime or movement, without exception, has crystallized around the figure of a single male leader. While these leaders cloak themselves in the social media garb of an all-powerful masculinity, in reality these men are nothing but a bunch of administratively incompetent, culturally provincial and historically illiterate gerontocrats.3

Despite their national differences, this gerontocracy is united by a single common experience. This experience was the historical zenith of the post-1945 period of US hegemony. To be more precise, the formative years of their childhood and their early teenage years were decisively molded by the American-dominated world of 1945-1973. Deep down, every single gerontocrat yearns to return to the same realm of childhood plenitude: a Hollywood sandbox where they finally get to play as world hegemon.4

One of the most brilliant innovations of The Squid Game was to translate the mid-20th century gerontocratic sandbox into early 21st century set design. The lethal competition portrayed by the series takes place in a series of brightly-lit, colorful spaces modeled on children’s playgrounds. Each of these playgrounds subsequently refunctions a popular children’s game into an adult killing zone. Although each round of the contest is conducted with a superficial veneer of fairness, the game as a whole is a blood-soaked lottery in which only one of the 456 contestants will survive.

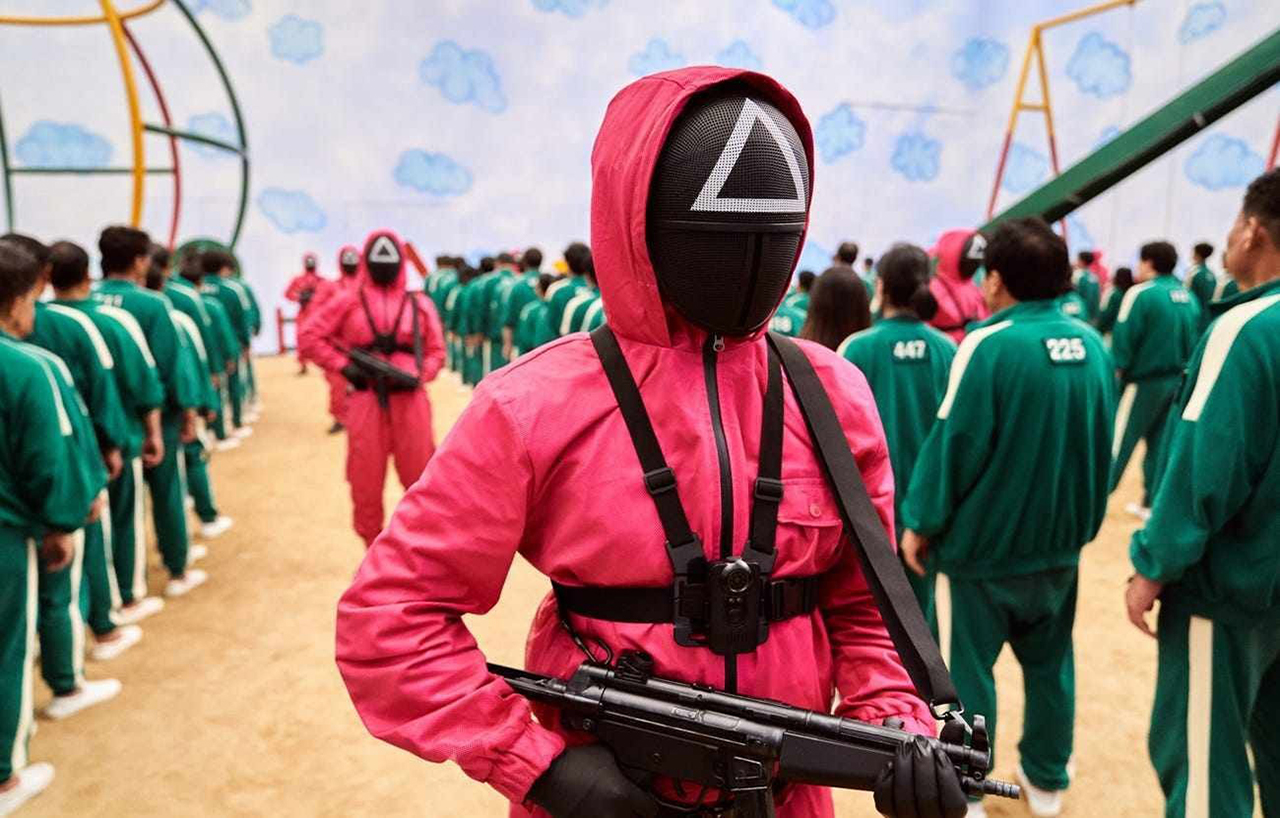

The left panel of Figure 1 below shows the playground utilized by the second round of the competition (we will explain the significance of the four symbols depicted on the wall in just a moment). The panel on the right shows the armed guards who enforce the rules of the game. They wear fluorescent pink uniforms reminiscent of semiconductor cleanroom suits, stamped with symbols indicating their rank (the lowest level of guards wear triangles, the higher level guards wear squares):

Figure 1. On the left, the four symbols used in the second round. On the right, the masked guards and unmasked contestants.

While the form of this playground mimics the gerontocratic sandbox, its symbolic content draws from one of the most powerful art-forms which has resisted plutofascism, namely videogames. The triangle and circle displayed on the wall are clear allusions to the two of the four symbols embossed on four of the buttons of Sony’s Playstation videogame controllers, which display a triangle, a circle, an X and a square. The star alludes to one of the most prominent symbols of Nintendo’s Supermario franchise, namely the collectible Power Stars which grant power-ups and other bonuses to players. Last but not least, the umbrella is an unmistakable reference to Capcom’s blockbuster Resident Evil horror-survival franchise, wherein players battle against the fictional Umbrella Corporation, which unleashes horrifying genetically engineered viruses on the world.5

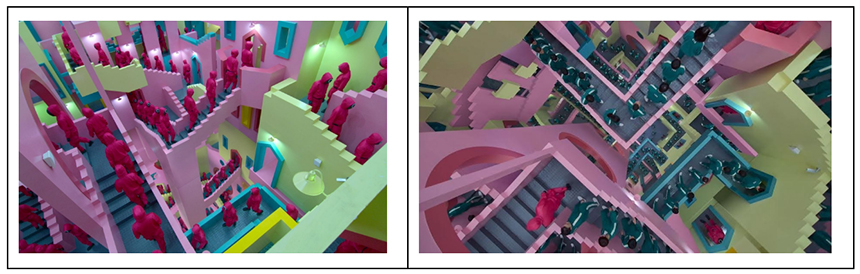

The Squid Game also borrows heavily from the toolkit of videogame user interfaces, which carefully craft their player controls and customization options to mesh with the overall aesthetic style of the game-world. One of the clearest examples of this is the arresting visual design of the staircase connecting the player dormitory to the various contest rooms, best described as the neon pastel update of M.C. Escher’s iconic print Relativity (1953).

Figure 2 below reproduces two shots of this staircase. The shot in the left panel employs a fisheye lens to generate the feeling of an unnerving proximity with the masked guards trudging to their stations, while the one in the right panel employs an overhead camera to generate the feeling of an equally unnerving distance from the unmasked contestants on their way to certain death:

Figure 2. The Squid Game’s staircase of doom.

The brilliance of this set design may help to explain why the single greatest narrative strength of The Squid Game – its capacity to showcase the imperial masculinity of plutofascism as a sandbox of doom – is also its single most profound weakness. The root cause of the problem is that the series focuses on the contradictions of a specifically South Korean imperial masculinity.

Readers with some familiarity with Korean history may object that Korea was never an official imperialist power in its own right, but waged constant defensive struggles for autonomy against neighboring empires for hundreds of years.6 This is true, but overlooks the fact that imperial masculinity was never just an ideology of conquest. It was also a set of mindsets, norms and dispositions internalized over decades and sometimes centuries of colonial rule by every colonized people.7

South Korea was no exception to this rule. After sixty years of overt colonization by the Japanese empire (1895-1945),8 postcolonial Korea split into two polities dominated by competing sub-imperial masculinities, the Kim dynasty of the north and the Rhee regime of the south. The two Koreas waged a bloody but inconclusive war between 1950 and 1953, the first of the proxy wars of the Cold War era. Following the armistice of 1953, South Korea’s citizens struggled for thirty-four years against a series of brutal dictatorships until the nineteen-day June Democratic Struggle ushered in the triumph of electoral democracy in 1987.9

But whereas most newly independent polities languished in the global periphery or the lower ranks of the semi-periphery, South Korea rose from the ashes of the civil war to become a successful exporter of consumer goods in the 1980s and 1990s, and high technology and mass media in the 2000s and 2010s. This industrial success came at the price of intense psychological pressure and cultural alienation, as South Korea rocketed in three decades from rural feudalism to urban capitalism.

While Korean firms such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai produce world-class smartphones, laptops and electric automobiles, its workers routinely suffer from despotic shopfloor management and excessive working hours, and its citizens struggle against semi-feudal family hierarchies and a drastically underfunded welfare state. Jean Kim has insightfully summarized the ways The Squid Game integrated almost every major social contradictions of contemporary South Korea into its storyline:

…It [South Korea] rose from an impoverished country in ashes to a global economic and entertainment powerhouse in little more than 30 years.

Yet South Korea is also an ancient, 5,000-year-old culture with deeply embedded social roots based on Confucian (and patriarchal) hierarchy. The country was isolated from the Western world for many centuries and accordingly nicknamed the Hermit Kingdom. The sudden superimposition of contemporary influences on the old underbelly of Korean culture has led to the confusion and angst highlighted in many of their recent works of film and literature. Although South Korea’s economic success has led to some waves of incoming immigration (represented in part by the touching Squid Game character Ali), the nation largely remains one provincially monocultural family crowded within half a peninsula and living mainly in high-rise buildings. With the advent of a stunning megarich class and, in equal measure, an exploited and indebted working class, all living on top of one another, both human ambition and embittered resentment cannot help but build. South Korea does not have the geographical size of the United States, where the rich have the space to hide in cloistered luxury, and the masses can be more easily fooled or distracted with a steady diet of propaganda.

The Squid Game cleverly highlights through its characters some of these conflicts: members of the cruelly subjugated migrant class, like Ali; the tragic confusion of North Korean refugees who leave one (still worse) version of hell for a different one, represented by the compelling character Sae-byeok (which means Dawn); the financial shark social climbers like Sang-woo, and more. There is also understandable modern ambivalence toward the Confucian deference to the elder class, the members of which can both anchor and destroy the social order, depending on their own underlying values; this conflict is captured in the complex character of Il-nam, and to some extent in Sang-woo and Gi-hun’s kindly, self-sacrificing elderly mothers, who embody perhaps the unsung heroes of Korean society.10

We will return to the character of Il-nam Oh at the end of this essay, since his identity is crucial to understanding why The Squid Game successfully captured the horrific essence of plutofascism but was unable to imagine the possibility of a democratic political alternative to such.

For now, it is worth emphasizing that the contradictions of Korea’s decades of internalized imperial masculinity, the warring sub-imperial masculinities of its postcolonial partition, and the liberating but also alienating effects of South Korea’s high-technology boom are all on prominent display in the character of Gi-hun Seong, the main protagonist of The Squid Game. Brilliantly played by prominent Korean star Jung-jae Lee, Gi-hun is a former automobile factory worker who lost his job after participating in a labor protest a decade prior to the events of the series.

Ever since then, he has been desperately trying to support his daughter, Ga-yeong (now ten years old), as well as pay the medical bills of his ailing elderly mother. Like millions of Koreans, he discovers his factory experience has been rendered worthless by the advent of the new high-technology economy. Adding insult to injury, Gi-hun’s divorced wife (Ga-yeong’s mother) is now partnered with a man with a steady job in the new high-tech economy.

Some of the most poignant scenes of the series show Gi-hun trying to overcome his crushing sense of personal humiliation and failure by being a good father to Ga-yeong, only to fail due to circumstances beyond his control. Hopelessly in debt and hounded by loan sharks, Gi-hun finally agrees to become a contestant in the Squid Game in hopes of winning a share of its $40 million jackpot.

To properly appreciate Gi-hun’s decision, it is important to remember that the South Korean dictatorships prioritized the creation of a national automobile industry as a means of creating a modern industrial economy, while the democratic governments of the post-1987 period saw the auto industry as a means of competing against their former colonizers, Japan. The Korean auto industry became the site of some of the most militant labor protests in East Asian history. Auto workers were key participants in the June Democratic Struggle, as well as the formation of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions in the mid-1990s. What this history means is that Gi-hun is motivated not just by the desire for personal redemption, but by the memory of a past industrial solidarity and by the sting of a wounded national masculinity.

Gi-hun’s mixture of personal and political motivations is paralleled by those of the five other contestants he befriends during the course of the contest, shown in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3. From left to right, Sang-woo, Gi-hun, Ji-yeong, Sae-byeok, Il-nam and Ali.

The panel on the far left depicts Sang-woo Cho (played by Hae-soo Park) as player 218, a junior classmate of Gi-hun who is trying to redeem himself after going bankrupt trading financial securities. He is standing next to Gi-hun Seong himself (Gi-hun is actually player 456 – the “5” is visible on his white T-shirt – but is temporarily wearing contestant 001’s tracksuit during that particular episode).

The center panel shows Ji-yeong (played by Yoo-mi Lee) as player 240, standing next to Sae-byeok Kang (played by HoYeon Jung) as player 067. Ji-yeong is on the run from the police after killing her abusive father, while Sae-byeok is an exile from North Korea seeking the funds to rescue her younger brother from North Korea’s dismal presidential monarchy.

The panel to the far right depicts an elderly man named Il-nam Oh as player 001. He is played by legendary Korean theater actor Yeong-su O, renowned for his portrayals of Buddhist monks as well as his roles in Korea’s version of the Shakespearean stage. While his reasons for entering the game are not immediately clear, he is in the late stages of a terminal ailment, and his uniformly benevolent and grandfatherly behavior towards the other contestants suggests he only wants the prize as a means of helping a needy member of his extended family. To Il-nam’s right is Ali Abdul (played by Anupam Tripathi) as player 199, a migrant worker from Pakistan who was swindled by his unscrupulous Korean employer and is just trying to support his wife and daughter.

The character of Ali is interesting for two reasons. First, this is one of the first positive depictions of South Korea’s community of 2 million foreign immigrants (about 4% of its total population) in Korea’s heretofore monocultural mass media. Second, it is overt acknowledgement of the vast South Asian audience for Korean technology and media exports. Ali became one of the unofficial fan favorites of the series, propelling Tripathi (who is from New Delhi, India and who speaks fluent Korean) to overnight stardom.

For most of the series, these six positive characters face off against two minor villains. These latter are rival contestants Deok-su Jang (played by Sung-tae Heo) as player 101, a gangster on the run from his mob boss, and Mi-nyeo Han (played by Joo-ryoung Kim) as player 212, an untrustworthy con artist. The solitary moment of poetic justice in the series is watching Deok-su and Mi-nyeo constantly attempt to swindle the other contestants and each other, but succeed only in triggering their reciprocal demise.

The story-telling arc of the series peaks in episode 6, titled “Gganbu” – an untranslatable Korean word referring to a childhood friend one could never, ever betray. Prior to the contest, the contestants are told to choose a partner for the next round. They all assume the competition will be a team activity, where two battle against two.

In reality, the contest is a duel to the death not between teams of partners, but between the partners themselves. The tension is heightened by the set where the contest takes place, an indoor replica of an ordinary South Korean urban alley lit by an impossibly nostalgic artificial sky. Not the least of the crimes of plutofascism is its transformation of childhood memories of the Hollywood media of the 1950s and 1960s, some of which was genuinely anti-colonial and critical of the US empire, into engines of revanchism.11

This episode also contains the single best line of the series, namely Ji-yeong’s sardonic quip to Sae-byeok after learning that only one of them will survive the contest: “This is the biggest tragedy since the Korean War.” In such moments, The Squid Game reveals the true depths of the class rage of South Korean workers at being swindled and exploited by Korea’s own plutocrats.

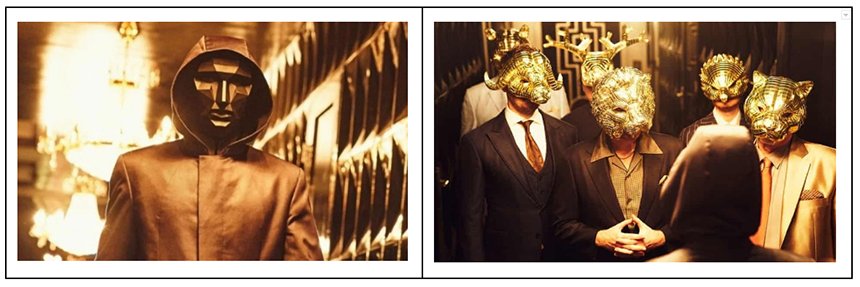

Where the series begins to unravel, however, is in its unmasking of the two main villains of the game. The first and most obvious villain is the Front Man (played by Byung-hun Lee), shown in the leftmost panel in Figure 4 below. He oversees security and the daily management of the game, and his mask is a cross between Italian futurism and one of Mussolini’s ghastly statues. The second villain is the original creator of the Squid Game, who is a member of the VIPs dressed in golden animal masks shown in Figure 4 on the right:12

Figure 4. The left panel shows the Front Man, while the panel on the right shows the VIPs.

Unfortunately, the arrival of the VIPs also marks the moment that the series’ critique of imperial masculinity begins to fall apart. Put more precisely, the series successfully depicts the violent imperial masculinity which fuels plutofascism, but cannot quite grasp the anti-colonial feminist solidarity which could defeat that plutofascism – a polite way of saying, there is no moment suggesting the possibility that the players and the guards could unite and rise up against the game.13

The first sign of trouble is the subplot of the police officer, Jun-ho Hwang (played by Ha-jun Wi), who discovers the existence of the Squid Game and manages to infiltrate the offshore island where the contests are held. At one point, he even assumes the identity of one of the guards, killing the latter and donning his mask to hide his identity.

The problem is that this entire subplot is a variant of the espionage thriller – that is to say, the James Bond-style drama of uncovering secrets. But game shows by their very nature do not have secrets, only prizes for the winners and penalties for the losers.

On closer examination, nothing about the Squid Game is really a secret. Each game is based on a popular children’s game well-known to the players. The contestants sign waivers absolving the game’s creators of responsibility for their deaths, and prior to each round, a majority of the contestants can decide to dissolve the holding of the entire game and return home unscathed. The second episode depicted the contestants voting to do exactly this, and they were allowed to return to their normal lives. While a majority later returned to participate in the second round, a significant minority did not.

If the game is truly legal, then the espionage thriller subplot is a pointless waste of time. If the game is truly illegal, then we are watching a bunch of poor criminals killing other poor criminals to entertain rich criminals – the scenario of the generic crime thriller. In that case, however, the stories of the contestants and their character arcs become a pointless waste of time. There is no middle ground between these alternatives.

This may explain why the longer the espionage thriller subplot goes on, the more it strains our sense of narrative credulity, until the entire subplot melts down completely in episode 8. This episode attempts to stabilize the unstabilizable by recourse to that staple trope of the South Korean costume drama, the tragedy of family members divided by competing feudal or dynastic loyalties.

When the guards finally entrap Jun-ho on the rocky promontory of a neighboring island, Jun-ho fires one shot at the Front Man, lightly wounding the latter. However, the Front Man signals the guards under his command to refrain from returning fire. Instead, he reveals his true identity as In-ho Hwang – the winner of one of the past Squid Games, and none other than Jun-ho’s long-lost missing brother.

But what defies all narrative credibility is the subsequent moment when In-ho shoots his brother in the same general part of the body he himself was just wounded in. This causes Jun-ho to fall into the ocean (it is possible the wound was fatal, but it is also possible the brother survived and floated to freedom). The patent unreality of the scene is seconded by a subsequent sequence which shows In-ho staring at his own reflection in a mirror, clearly consumed with guilt.

It is possible the director wanted to suggest the entire subplot was nothing but In-ho’s own psychological projection, a reiteration of a past trauma rather than an actual event. Even if this were true, the script cannot have it both ways. Either we are watching a game show with realistic characters who make realistic choices, or we are watching an espionage thriller where unrealistic heroes ferret out unrealistic secrets, or we are watching a costume drama where unreal warriors battle with unrealistic abilities.

While the implosion of the espionage thriller subplot damages the credibility of the series, it does not completely derail its momentum. The series generates one final moment of near-greatness in the form of the face-off between the three surviving contestants at the end of episode 8.

On one level, this face-off could be read in terms of Korean national allegory: an ordinary South Korean worker (Gi-hun) faces off against South Korea’s predatory neoliberal elites (Sang-woo), while North Korea’s dysfunctional presidential monarchy (Sae-byok) can only look on from the sidelines. On a deeper level, the scene could be read as a critique of the corporate media monopolies (the VIPs watching the action on their giant wall-screen) who exploit the hunger of transnational audiences for spectacles.

Where national and global allegory converge is the tantalizing possibility that Gi-hun and Sae-byeok might vote at the last second to stop the game, overriding Sang-woo’s clear desire to battle to the end. This is the possibility of a planetary liberation movement capable of uniting everyone against North Korean-style autocrats as well as South Korean-style plutocrats.

Instead, the storyline disintegrates into the South Korean version of the John Wick thriller. 14 This thriller is set in motion by the unmasking of the ultimate villain in episode 9. Gi-hun, the sole survivor of the final standoff, learns that Il-nam Oh was no kindly grandfather, but the plutocrat who created the Squid Game in the first place. Il-nam’s terminal illness was real enough, but he decided to play-act as one of the contestants out of sheer boredom and the excitement of living his last moments on the cusp of constant danger. When Il-nam passes away due to natural causes during the episode, Gi-hun decides to seek vengeance on the game’s remaining perpetrators.

In fairness to the makers of the series, the final episode does what almost all seasonal television series do, namely wrap up the main story threads of the season while keeping the door open to its renewal (Variety recently reported that Netflix has indeed renewed the series for one more year). Yet the dazzling promise of The Squid Game, the gambit which kept hundreds of millions of viewers glued to their screens, was not the possibility of watching an even more garish and blood-soaked version of plutofascism’s game of death. It was the possibility that the participants might finally break the rules of the game – and end plutofascism forever.

There is already a working model of game-breaking in the form of Hideo Kojima’s blockbuster science fiction thriller Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots (2008). At the end of this videogame, the protagonist discovers the existence of an elderly archvillain named Zero, the equivalent of Il-nam Oh. Zero was responsible for creating an orbital network of AI (artificial intelligence) supercomputers and AI-controlled private military companies called the Patriots. This network has enslaved humanity by stoking an endless series of proxy wars and then selling weapons and supplies to both sides.

What made MGS4 a classic of the ages was not just its pungent critique of Wall Street plutocrats and the US military-industrial complex. It was the fact that the protagonist, Solid Snake, was part of a planetary team who pulled together to liberate humanity from the Patriots and their proxy wars.

The closest The Squid Game came to evoking this solidarity was the brief and shining moment in episode 2 when its contestants voted, by the thinnest of majorities, against the continuation of the game. If the ending of the series could not imagine any other outcome than the continuation of plutofascism’s murder spree, then that vote still holds out the promise of a world where human beings would no longer have to kill each other to survive.

Footnotes

1 In broadcast television, this is a lineage which can be traced back to Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner (1967), a parody of the James Bond spy thriller set in the Welsh tourist resort of Hotel Portmeirion. In cinema, it has inspired science fiction dystopias everywhere from Paul Michael Glaser’s The Running Man (1987) and Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000) to Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games novels and films (2008-2015). In videogame culture, it inspired franchises as diverse as Spike Chunsoft’s Danganronpa visual novels (2010-2015) and the multiplayer scrimmages of PUBG (Player Unknown: Battleground) (2017-present).

2 To borrow an insight from world-systems theory, whereas early 20th century fascism was a reactionary response to the demise of the British world hegemony of 1815-1914, early 21st century plutofascism is the reactionary response to the end of the US world hegemony of 1945-2008.

3 Duterte was born in 1945, Trump in 1946, Modi in 1950, Putin in 1952, Xi in 1953, Erdogan in 1954, Bolsonaro in 1955, Orban in 1963 and Johnson in 1964.

4 One of the little-known factors which caused millions of ordinary males to fall prey to the plutofascist lure of fake imperial masculinity was demographics. Since 1973, the majority of women on the planet have gained access to education and to birth control, reducing world fertility rates from 4.41 in 1973 down to 2.3 in 2021. At the same time, women have entered the workforce in large numbers in every society on earth. Plutofascism’s fake imperial masculinity is the doomed fantasy of returning to the pre-1973 era of the despotic male control of female sexuality and exclusively male access to prestigious jobs.

5 The umbrella was also one of the most prominent symbols of Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner series.

One of the little-known factors that caused millions of ordinary males to fall prey to the plutofascist lure of fake imperial masculinity was demographics. Since 1973, the majority of women on the planet have gained access to education and to birth control, reducing world fertility rates from 4.41 in 1973 down to 2.3 in 2021. At the same time, women have entered the workforce in large numbers in every society on earth. Plutofascism’s fake imperial masculinity is the doomed fantasy of returning to the pre-1973 era of the despotic male control of female sexuality and exclusively male access to prestigious jobs.

6 Korea resisted annexation by the Ming and Qing Chinese empires between 1366 and 1911, and then resisted colonization by the Japanese empire between 1895 and 1945. After 1953, North Korea and South Korea resisted neocolonization by Maoist China and by the US hegemon, respectively.

7 The immense power of this internalization helps to explain why the overwhelming majority of polities which managed to free themselves from imperial rule during the 19th and 20th centuries ended up relapsing back into neocolonial despotisms depressingly similar to their colonial predecessors. The examples are legion, and include everything from Brazil’s 68 years of constitutional monarchy between its 1823 independence from Portugal and Pedro II’s abdication in 1891 to Algeria’s 57 years of presidential monarchy between its 1962 independence from France and Bouteflika’s 2019 abdication.

8 Korean workers organized numerous trade unions in the 1920s in response to Japanese colonial exploitation. Seung-ho Kwon and Chris Leggett (1995). “Origins of the Korean Labour Movement.” Policy, Organisation and Society 10:1 (13-15).

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10349952.1995.11876634

[9]South Korea did experience a brief moment of democratic self-rule between 1960 and 1961, the period known as the Second Republic. The Republic ended when Chung-hee Park seized dictatorial power in a coup in May 1961.

[10] Jean Kim. “What Squid Game Is Really About: How decades of Korean trauma have spawned a pop culture phenomenon.” The American Spectator. October 16, 2021. https://theamericanscholar.org/what-squid-game-is-really-about/.

[11]The examples include the anti-imperial science fiction of Fred Wilcox’s Forbidden Planet (1956), the anti-nuclear satire of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1960), and the musical works of Jimi Hendrix and the Velvet Underground,.

[12]These golden animal masks are possibly a nod towards Eisenstein’s use of shots of animals to symbolize the decadence of Czarist-era capitalist elites in Strike (1925).

[13]This anti-colonial feminist solidarity was a prominent subtext of every single one of the classic Hong Kong action films of the 1973-2008 conjuncture. For example, Bruce Lee’s iconic role in Robert Klouse’s Enter the Dragon (1973) was framed as a mission to avenge his sister. In John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992), super-cop Tequilav must learn to be a childcare provider by rescuing infant children from a burning hospital.

[14]One of the reasons for the Wick franchise’s success was that it starred Keanu Reeves as a former hitman who is now waging his own private war against criminal mobsters, i.e. it blurs the line between lawfulness and criminality the same way the James Bond secret agent was nominally under civilian control, but had a license to war against enemy agents.

The author is an independent scholar of digital media, video games and transnational media.