At a time when our collective conscience is being shaped more and more through media trials and WhatsApp forwards, when right wing regimes are generating fake news to suit their narratives, when videos of lynchings and encounter killings are doing the rounds to accustom people to the idea of state violence, when media representations are continuously creating and demonizing the ‘other’, it becomes imperative to unpack the making of the collective conscience, writes Jhelum.

“The incident, which resulted in heavy casualties, had shaken the entire nation and the collective conscience of the society will only be satisfied if the capital punishment is awarded to the offender. The challenge to the unity, integrity and sovereignty of India… can only be compensated by giving the maximum punishment… The appellant, who is a surrendered militant and who was bent upon repeating the acts of treason against the nation, is a menace to the society and his life should become extinct. Accordingly, we uphold the death sentence.”

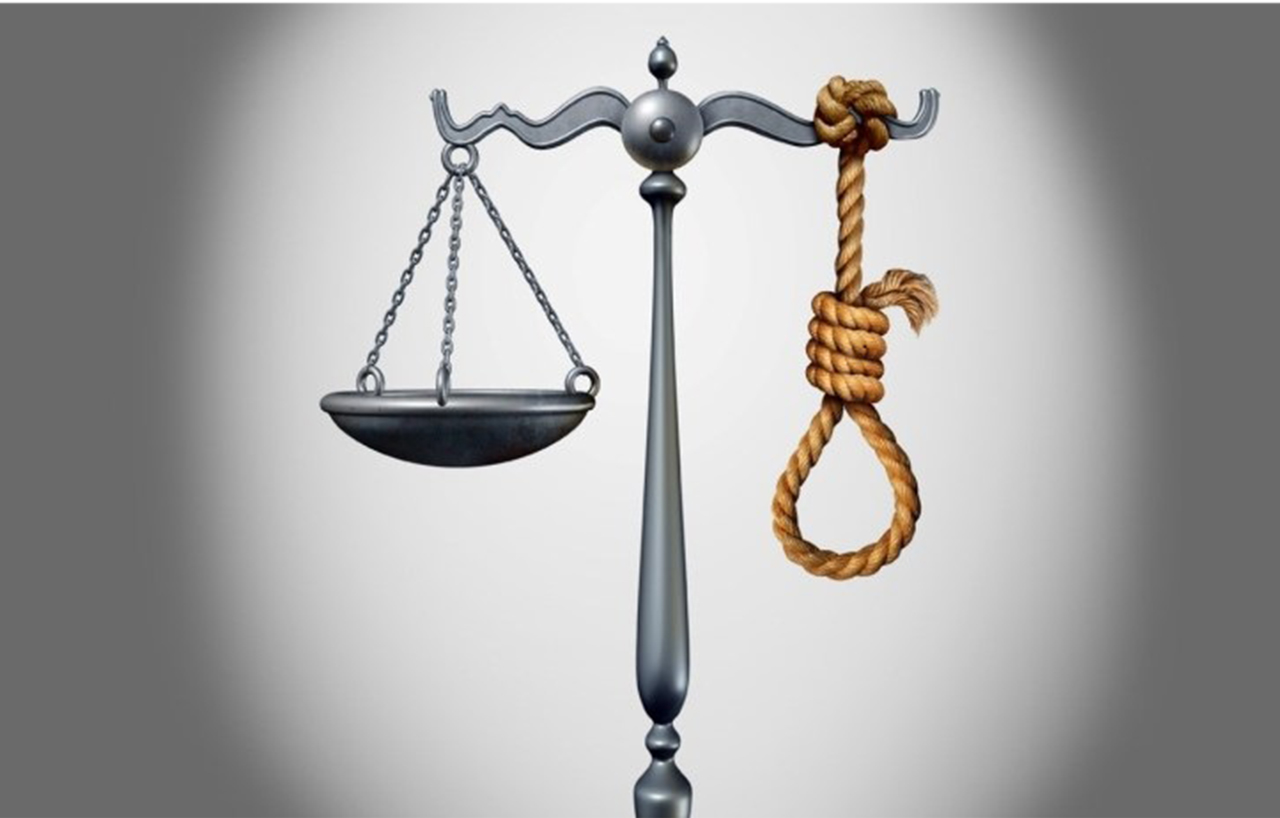

When the Supreme Court sentenced Afzal Guru to death in 2005 to satisfy the ‘collective conscience’ of society despite there being no conclusive evidence that tied him to the crime, it set a precedent. The highest court of law essentially chose to adjudicate based on collective conscience or mob sentiment rather than any notion of justice. While a section of activists protested this decision and warned us of the consequences, tediously pointing out the unfairness of it all, their voices were drowned in the collective baying for the blood of a ‘terrorist’. The summoning of ‘collective conscience’ by the Supreme Court therefore became a norm for justifying capital punishment. We have seen it in case of the Jyoti Singh rape case in 2012, just as we have seen it in the case of the rape and murder case of a 22 year old woman in Bombay. Recently, as the arrest of Davinder Singh once again resurrected the ghost of Afzal Guru, bringing back the questions that his wife, his lawyers, and several activists have been asking since his trial, as we stand just a few days before the accused of the rape and murder of Jyoti Singh are about to be hanged to once again satisfy our ‘collective conscience’, it is important to ask: whose collective conscience is it anyway? How is this collective conscience manufactured? And who decides which case would knock on our collective conscience?

While talking about the absurdity of collective conscience, Arjun Mohan talks about the Nanavati case in Bombay,

“In April 1959, KM Nanavati, a commander in Indian navy, shot dead his friend for 15 years Prem Ahuja. Ahuja was having an illicit relationship with Nanavati’s wife while the commander was away on work. Nanavati surrendered after the act and was trialed by a jury of 9 members of Greater Bombay sessions court. Though it was clear from the beginning that Nanavati had killed Ahuja in cold blood, the commander acquired a hero image during the trial. Thousands used to gather in front of the court when the arguments happened and Nanavati used to be get an arousing welcome with slogans and clapping whenever he arrived at the court. A tabloid Blitz eulogized his act as a loving and wronged husband avenging the wrongs done against his family by a playboy. This version of the story became so popular that Blitz sold for Rs 2 per copy whenever it ran this story while its original price was 25 ps at that time. Rallies happened in Mumbai supporting Nanavati and finally the jury acquitted Nanavati with a 8-1 verdict. The “collective conscience” was obviously for setting Nanavati free (or at least it seemed so) though he committed a murder in cold blood.”

The other factor that also played a role in shaping the collective conscience in this case is the impunity that is usually given to men in uniform who are deemed to be protectors of the ‘collective’. While 1959 was a different time, and the Bombay court and later Supreme court, found Nanavati guilty of murder and sentenced him to life imprisonment, this case forces us to reflect not only on the arbitrariness and absurdity of the collective conscience argument, but also on its impact, its strength. The witch hunts of Afzal Guru and SAR Geelani, some 40 years later, will stand witness to how the ‘collective conscience’ had finally grown to make a dent on our judicial system, on our sense of justice.

At a time when our collective conscience is being shaped more and more through media trials and WhatsApp forwards, when right wing regimes are generating fake news to suit their narratives, when videos of lynchings and encounter killings are doing the rounds to accustom people to the idea of state violence, when media representations are continuously creating and demonizing the ‘other’, it becomes imperative to unpack the making of the collective conscience. For those who have been following the trial of Afzal Guru know of the way the campaign ‘Hang Afzal’ was trumped up before the verdict was out. One sees almost a similar kind of demonization of ‘rapists’ in case of the rape and murder of Jyoti Singh in 2012 and in the more recent case of Priyanka Reddy. In both the events, we have seen how our collective consciences were invoked, how national outrage poured over media suppressing the feminist voices that were trying to reason, to campaign against death penalty. While the four rape accused were still able to reach the doors of the court in 2012, this time we saw how the suspects were eliminated in a fake encounter, with the police playing the role of judge, jury, and executioner. So what is it that enrages our collective conscience that is otherwise oblivious to atrocities happening in Kashmir, in Manipur, in Assam, and in Bastar? What is it that enrages our collective conscience that otherwise turns a blind eye to violence against Dalits, Muslims, and queer people? Why do we not see similar media portrayals (of rape accused as demons) when the accused are godmen, ministers, or men in uniform? Why has our collective conscience not spoken out against rape being used as a weapon of war?

So is collective conscience only evoked to hurry ‘justice’ when the state finds itself in a sticky spot? Is it conflated with nationalist sentiment such that it assumes a jingoistic fervour and adorns the garb of serving the ‘greater good’ for which all other questions of fairness, of justice needs to be kept aside? The arrest of Davinder Singh has raised many questions about his involvement in the attack on the Parliament, and also about his involvement in the Pulwama attack. But the two people, Afzal Guru and SAR Geelani, who could have shed some light on these questions are no longer here. The four accused of the brutal rape and murder of Priyanka Reddy have been ‘encountered’ thereby absolving the state from its responsibility of creating safe spaces, of sensitising people, of eliminating rape culture. The ones convicted in the Jyoti Singh rape case have been declared to be hung on 1st February, 2020. The question to ask is, can we as a society wash our hands clean of our responsibility, our complicity in creating, nurturing, and sustaining rape culture by making examples of four people, who do not have the necessary socio-political clout to call us out on our selective outrage? More importantly, does the state that uses rape as a disciplinary tool to suppress movements, to curb dissent, have any moral authority to make examples of others for committing the same crime? Can we allow ‘collective conscience’ that is constantly manipulated, shaped by paid media, by the powers that be, to dictate judicial procedures? Can we address structural violence by merely demonising individuals and executing them?

When Hannah Arendt attended the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the man who was responsible for managing and facilitating the mass deportation of Jews to concentration camps in Nazi Germany, she was startled by the mediocrity and ordinariness of the man in comparison to the staggering crimes he had committed. Eichmann’s consistent claims that he had no intentions, whether good or bad, that he was only following instructions, only being an obedient servant, troubled Arendt. He refused to feel remorse or feel anything as he said he merely did what he did as a bureaucratic process. This forced Arendt to confront what she termed as the ‘banality of evil’. Today, in times of mob lynching, where ordinary people, where our collective conscience is becoming judge, jury, and executioner, where we have so othered people that we refuse to think of them as ‘human’, we perhaps also need to think of the violence of collective conscience. In times when we are constantly creating and producing the ‘other’ – the Kashmiri, the Muslim, the Dalit, the ‘anti-national’, the terrorist, the ‘urban Naxal’ – we need to probe into our own complicities in building this ‘new normal’. The ‘Me Too’ movement had disrupted this image of the rapist as the ‘monster’ by bringing to the fore how assaulters are not extraordinary perverts but people amongst us, our friends, comrades, partners, fathers, brothers, neighbours, ordinary people like us. Today, when any woman/trans/queer person voicing their dissent or speaking out is silenced with rape threats, labelled as ‘randi’, ‘slut’, ‘whore’, when our WhatsApp groups are flooded everyday with misogynist memes, rape jokes, when any survivor calling out their assaulter is disbelieved, can we really absolve ourselves and be the ‘collective conscience’ clamouring death penalty for rapists?

When evil becomes banal, ordinary people participate in it. Before clamouring for capital punishment, we need to probe into the power structures that create ‘others’, that create the ‘collective conscience’. The hysteria of ‘collective conscience’ gives one the liberty to not think, to be so obsessed and consumed with the monstrosity, the non-humanness of the ‘other’, that one overlooks the loopholes, the complicities of the system. As we bay for the blood of the four accused, who belong to the lowest strata of society, the ‘migrant’, the ‘lower class’, the ‘lower caste’, the Brahminical patriarchal state slowly cements its place, strengthening its hold, as the ‘deliverer of justice’ while completely obfuscating its role in creating and sustaining rape culture. Just like during the trial of Afzal Guru, in the mass hysteria demanding that we ‘Hang Afzal’, we forgot to ask why a surrendered militant who was tortured by DSP Davinder Singh would be trusted by ‘militants’ to be the key person in the Parliament attack, or why did Afzal Guru say he was asked to arrange logistics for the people in Delhi by Davinder Singh, who was later awarded for his gallantry by the state?

When the judiciary gives in to being dictated by collective conscience, we lose claims to all sense of justice. Like we did in the recent Babri Masjid verdict where the court chose majoritarian faith over addressing injustice, over retaining the secular fabric of the country. Today, when we see our own friends, neighbours, family spouting vengeance, spreading communal venom, justifying genocide, speaking in favour of extermination of communities, we are confronted with the ‘banality of evil’. Talking about crimes that the state commits in its name, Hannah Arendt pointed out how the justification cited is always ‘necessity’, as ‘emergency measures’ such that the state can preserve its power and assure the continuance of the existing legal order as a whole. However, the question that needs to be asked here remains about capability of human beings to think, as Arendt writes,

“that human beings be capable of telling right from wrong even when all they have to guide them is their own judgment, which, moreover, happens to be completely at odds with what they must regard as the unanimous opinion of all those around them.”

In totalitarian regimes, when the state is constantly weaponsing collective conscience to suit its agendas, to create mobs out of ordinary people, it becomes critical to raise these questions, to think, to reflect, and ask ourselves, can the master’s tool ever dismantle the master’s house?

Jhelum is a researcher and involved in activism.