Emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil fuels are causing catastrophic climate change, and threaten to destroy all human life on our planet. Simply, climate change is the single greatest threat facing our species since our emergence as a species a half million years ago. It is a bigger threat than the biggest of our world wars. It is more terrifying than the worst of our Cold War nuclear nightmares. Writes Dennis Redmond.

Business as usual is over.

This is the central message of the 2018 climate youth strike, the biggest coordinated youth protest in human history. It is the message of the Fridays for the Future student strike wave inspired by Greta Thunberg, and the massive protests inspired by Bill McKibben’s 350.org and Extinction Rebellion. It is the message of Canada’s indigenous peoples fighting against planet-killing tar sands projects, as well as the citizens protesting against coal mining in Queensland, Australia.

Above all, it is the message of the scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the scientific body charged by the members of the United Nations to analyze the effects of climate change.

In November 2018, the scientists of the IPCC issued a report which will go down in history as one of the turning-points of our species. The report has hundreds of pages and thousands of scientific references, but its message couldn’t be simpler.

Emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil fuels are causing catastrophic climate change, and threaten to destroy all human life on our planet. Simply, climate change is the single greatest threat facing our species since our emergence as a species a half million years ago. It is a bigger threat than the biggest of our world wars. It is more terrifying than the worst of our Cold War nuclear nightmares.

That’s why most of the IPCC report doesn’t waste our time painting scenarios of global doom. Instead, it gives us a blueprint for global action.

We have eleven years to decarbonize our economies and societies. That means the planet must cut its CO2 emissions in half by 2030, and reduce total emissions to zero by 2050.

Either we get this done, or we are done as a species.

So how do we get there?

The first step is to identify the largest sources of CO2 emissions in the world. The second step is to identify the industries generating those emissions. The third step is to mobilize communities to change those industries, by building a green energy commons for all.

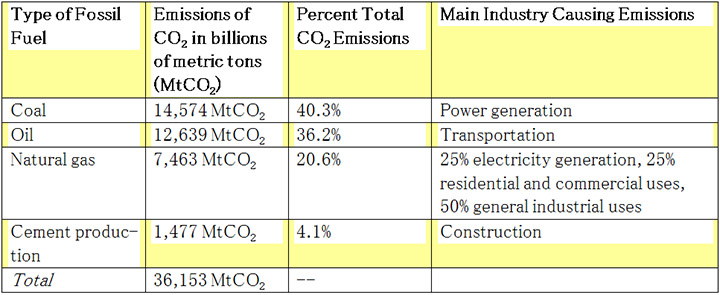

According to data from the Global Carbon Atlas, total world emissions of CO2 in 2017 reached 36,153 MtCO2, the scientific name for millions of metric tons of carbon dioxide. We have to cut that down to 18,077 MtCO2 by 2030, and then to zero by 2050.

Here are the four largest types of emissions, and the industries generating them:

Table 1. Largest sources of world CO2 emissions in 2017.

Coal is used primarily for power generation. Since it is the largest single source of emissions — about two-fifths of the total — we will have to build massive amounts of solar, wind and storage capacity in every country on earth, while shutting down every single coal plant.

We can afford to do this, because renewable energy follows the logic of the information revolution, in the sense that it constantly gets cheaper over time. In 2019, the long-term cost per kilowatt-hour of building and running a solar power plant in tropical countries with lots of sunshine fell below the long-term cost of building and running a coal plant, a concept called grid parity. From now on, it is less expensive to build and operate solar plants in the tropical regions than to build coal plants, and of course the price of solar will continue to fall for decades to come.

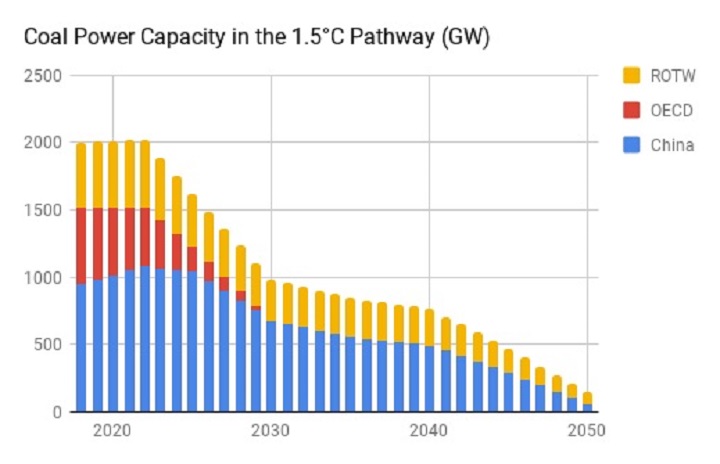

It is true that low-income and middle-income nations like India and China still depend on coal for most of their electricity. That’s why the IPCC report argues that in the interest of planetary fairness, coal plants ought to be closed first in the high-income nations responsible for about two-thirds of all CO2 emissions since 1750, and only later by the less wealthy nations who were least responsible for past emissions. Greenpeace has a chart of what such a phased shutdown might look like:

[Graphic courtesy of Greenpeace: https://endcoal.org/2018/10/new-ipcc-report-calls-for-steep-reductions-in-coal/]

The only problem with this chart is that it is not ambitious enough. Coal is not just the world’s worst planet-killer, it devastates the landscapes it is mined from, it poisons and kills the miners who dig it up, and it generates toxic air pollution which kills millions of people (especially in China and India) when it is burned.

Given that solar is now cheaper, it is sheer financial insanity to build a single new coal plant in any tropical country. In fact, the combination of solar plus storage is uniquely suited to bring affordable electricity to rural communities far from urban centers, something especially important for the majority rural nations of South Asia and Africa. In Bangladesh, villagers are beginning to construct their own solar microgrids, while rural households in Kenya are switching from expensive and dangerous kerosene lamps to cheaper and safer solar lamps. Solar can also power the pharmacies, hospitals and schools rural communities urgently need.

For this and many other reasons, the citizens of planet Earth need to put their foot down and stop all new coal mines and coal plants. This includes the coal plants financed by China’s belt-and-road initiative (BRI), a state program designed to encourage Chinese companies to finance infrastructure spending outside of China. While China invests heavily in electric autos and solar energy, its corporations are among the world’s biggest carbon polluters. Just recently, climate change protests convinced the largest banks of China and many other nations to sign on to the Green Finance Leadership Program, mandating low-carbon and zero-carbon investment in future BRI projects — but much more needs to be done.

The second largest source of CO2 emissions is oil, which is used primarily for transportation. The planet burns about 100 billion barrels of oil every day, three-quarters of which is consumed by autos and trucks. Another 12% is consumed by aviation, and 2.2% by maritime shipping.

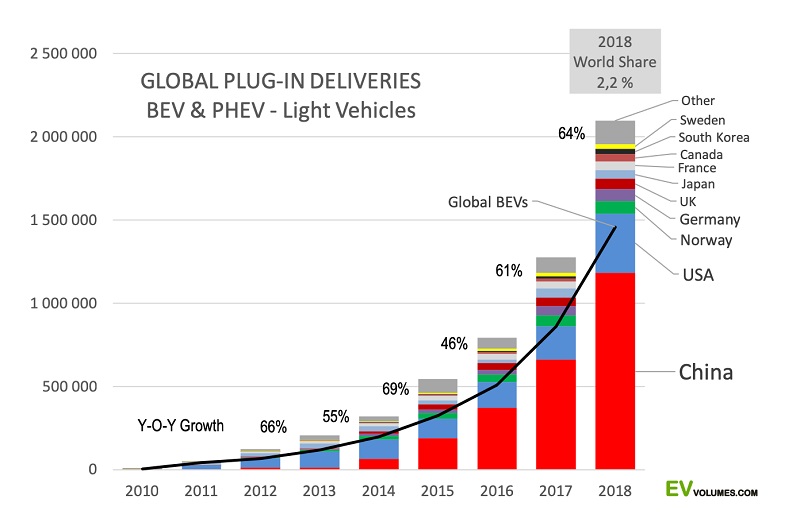

The first priority is to replace the 1.4 billion gas-powered vehicles on the planet’s roads with battery-powered EVs (electric vehicles), energized by renewable solar and wind. This is achievable because the main cost of an EV is its battery, and batteries get cheaper every year, just like solar. Analyst group Bloomberg New Energy Finance noted that the average cost of auto batteries fell from $1,160/kWh in 2010 down to $176/kWh in 2018, and will continue to fall in the future.

Collapsing battery costs are the secret behind the explosive growth of highly-regarded EV makers like US-based Tesla and China-based BYD, makers of some of the most popular emission-free autos and emission-free electric buses in the world. In fact, world sales of EVs skyrocketed from almost nothing in 2010 to 2.1 million in 2018:

Graphic courtesy of EV Volumes: http://www.ev volumes.com/country/total-world-plug-in-vehicle-volumes/

This is progress, but those 2.1 million EVs are still only 2% of worldwide auto sales of 90 million. To cut CO2 emissions from oil in half by 2030, we need to do much more. Every village, town, city, federal state and nation-state on Earth needs to invest heavily in zero-carbon mass transit systems, a.k.a. green mobility for all.

That means integrated and affordable networks of electric subways, electric buses, electric taxis, electric rickshaws and electric bicycles. As early as 2022, we will also have to start building networks of electric aviation (eVTOLs and electrified planes) and electric maritime shipping.1

Replacing gas-burning cars with EVs will also remove vast amounts of toxic air pollution from the world’s cities. Unlike lead-acid batteries, which are lethal to human beings, lithium batteries are non-toxic and can be easily recycled to make new batteries.

It is especially important to electrify urban commuter buses because they serve large numbers of passengers, are constantly on the road, generate significant pollution, and burn large amounts of oil. In 2017, the Chinese city of Shenzhen led the way by switching its entire bus fleet to electric, and now Paris and New Delhi are following suit.

Of course, producing EVs still requires enormous amounts of metal, glass, tires and other materials which despoil the environment. For that reason, it will be important to move away from the current of model of universal car ownership, and towards a society of shared mobility for all.

The third largest source of CO2 emissions is natural gas. Worldwide, about a quarter of all natural gas is used for electricity generation, and can be replaced by solar, wind and storage just like coal. This is beginning to happen in places like Oxnard, California, where a community campaign convinced the local utility company to build a zero-carbon battery storage system, instead of a carbon-emitting natural gas plant.

Another quarter of all natural gas is used for commercial and residential heating and cooling. Moving to zero-carbon buildings will require retrofitting buildings with electric heating and cooling systems, heat pumps, and ultra-efficient refrigeration and air-conditioning technology. The remaining half of all natural gas is used for a variety of industrial purposes, which will require a similar combination of retrofitting and electrification.

The good news is that citizens around the world are beginning demand zero-carbon buildings and industries, by changing building codes and investing in electric mass transit. In just the month of April, New York City and Los Angeles issued their own versions of city-specific versions of a Green New Deal. Corporations are also beginning to respond to rising public pressure, as the number of Fortune 500 companies with an explicit goal to use 100% renewable energy rose from 23 in January 2017 to 53 in February 2019.

The fourth and final source of CO2 is from cement production, which nominally comprises 4.1% of all emissions. However, this number is misleading, because it counts only the CO2 released during the initial conversion of limestone, the main raw material of Portland cement. The production process also requires large amounts of power from fossil fuels, especially coal, which means cement is ultimately responsible for 7% of the world’s CO2 emissions.

Most cement-related emissions are due to the accelerated urbanization of most Asian and African nations, which has triggered an immense construction boom throughout the industrializing world. In 2017, China accounted for 679 MtCO2 or half of all cement-related emissions, while the nations of South Asia and Africa accounted for another 129.7 MtCO2 and 78 MtCO2, respectively (by contrast, the heavily urbanized nations of the European Union generated only 71.8 MtCO2).

The solution is a combination of electrification and a switch to low-carbon forms of cement over the short term, and zero-carbon cement over the long run. Promising experimental versions of zero-carbon exist and are being used in construction projects, but do require additional research and development to become widespread.

In summary, we need to (1) build massive amounts of solar, wind and storage capacity, (2) shut down all of our coal plants and eventually all the natural gas plants, (3) replace 1.4 billion gas-burning vehicles with EVs and electric mass transit, (4) retrofit our buildings to be zero-carbon, and (5) switch to zero-carbon cement.2 In short, we need a program of green energy, green mobility, and green infrastructure for all.

This requires a mobilization of public resources on a scale comparable to the military spending of WW II, or to the military-industrial expenditures of the Cold War. Every single gas station must have its own electric chargers for EVs, every neighborhood must have its own electric taxi, electric bus and electric rickshaw stands, every apartment block must have its own solar heating or PV system, and every government office and commercial building must have its own zero-carbon roadmap. This could look like the Green New Deal outlined by US Congressional representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Edward Markey for the United States. It could also look like Yanis Varoufakis and DiEM25’s admirable program of a Green New Deal for Europe.

Above all, this mobilization will require a massive and sustained political campaign against the corporations whose business model is literally destroying the planet — the oil, gas, coal and cement industries, the gas-powered automobile industry, and extractive mining industries. While many of these corporations are American and European, some of the largest and most powerful of them are Brazilian, Chinese, Russian, Indian, Indonesian, Mexican, Saudi Arabian, South African and Turkish. Regardless of their nationality, they wreak the same destruction everywhere, and we citizens of the world have to unite to stop them.

The era of business as usual is over.

The epoch of struggle has begun.

Endnotes

- For aircraft, Airbus and Uber plan to roll out commercial services of electric air taxis or eVTOLs (electric aircraft capable of vertical take-off and landing) by 2022. These eVTOLs are simply bigger versions of the battery-powered drones already used as mobile cameras by hobbyists and Youtubers. However, improved battery technology will be needed to create medium-haul electric aircraft comparable to the Boeing 737 or Airbus 320. The electrification of maritime shipping will require a similar phased transition. Small ships can be powered by today’s batteries, but improved models need to be invented to power supertankers. However, the UNCTAD estimates 29% of the world’s maritime fleet, as measured by dead-weight tonnage, consisted of oil tankers in 2017. Switching away from oil to electricity will allow most of these tankers to be converted to other uses, significantly reducing the overall CO2 emissions of shipping.

- Over the long-term, we will also need to invent new technologies of carbon sequestration in order to recapture the CO2 already in the atmosphere, but the priority should be on reducing our emissions here and now.

Cover Image courtesy : Alamy stock photo

The Author is Dennis Redmond is an independent scholar of digital media, videogames and transnational media.