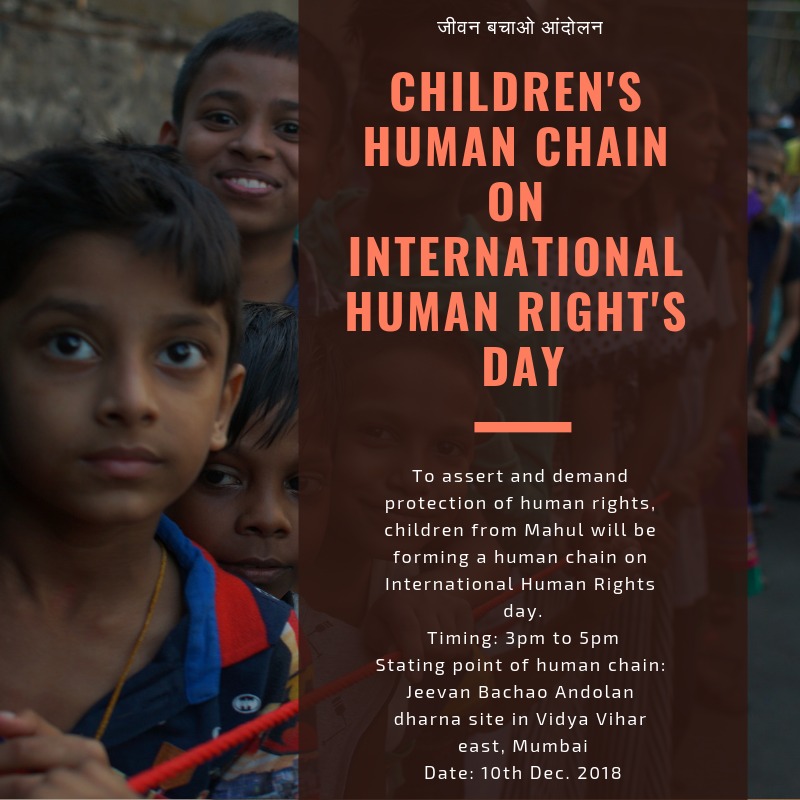

On 10th December, the International Human Rights day, the residents of Mahul in Mumbai, led by the children took out a rally from their dharna site next to the VidyaVihar Tansa pipeline, demanding right to life and right to housing. The ongoing dharna of thousands of people asking for relocation to proper rehabilitation quarters stepped into its 44th day on this day. A GroundXero report. You can read our ongoing coverage of the Mahul agitation here: “Evicted Mumbai slum residents occupy footpath as protest”, “Mahul Residents Continue Protest, Demand Rehabilitation for All, Show Black Placards to CM Fadnavis”, “Women Lead Mumbai Anti-Eviction Struggle: Four Interviews”, “Mahul : Children Protest for Right to Childhood”.

.

In 2009 the Bombay High Court ordered the forcible eviction and clearance of all hutments within 10 meters of the Tansa water pipeline – one of the major sources of water supply for the city of Mumbai, cutting through nine administrative wards. The reason cited then was these “illegal slums” are a threat to the security of the area. Later however, the authorities came up with a new plan: a $45 million, 24-mile cycling and jogging track along the length of the pipeline. On May 13 last year, nearly 1,000 houses near the Tansa water pipeline in Ghatkopar and Vidyavihar in Mumbai were razed to the ground by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). According to some estimates, the total number of households demolished along the entire stretch of the pipeline was around 20,000. The forcefully evicted residents were pushed into Slum Rehabilitation buildings located in the industrial area of Mahul, outside of the city. Mahul is one of the most toxic and polluted areas in the country, and has been described by people as “Mumbai’s Toxic Hell”. In contravention with not only Court orders and Supreme Court guidelines, but also with the UN standards for ‘adequate housing’, these people were exposed to the highly fatal chemically polluted water and air of Mahul, far away from where they had been living for decades. Demanding proper rehabilitation, the Mahul residents have been camping on the footpath opposite to their demolished basti site, in VidyaVihar, for the last 45 days.

Mahul is only one example of the acute housing crisis everywhere in the country. India has the largest number of urban poor and landless people in the world. According to the 2011 census, approximately 13.75 million households or approximately 65 – 70 million people reside in urban slums. “In some cities, such as Mumbai, those residing in slums represent close to 50% of the urban population, and cities like Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Kolkata account for more than 50% of total households living in slums in India,” read a press statement by the UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, Leilani Farha, after her India visit in 2016. Farha also talked about the general issue of homelessness in the country. “Data on the number of homeless people based on the 2011 census appears to under-represent the figure at 1.8 million, while researchers have indicated that the figure may be closer to 3 million people,” she added.

Day 44 of their occupation of the Vidya Vihar footpath. Mahul residents still waiting for proper legally mandated rehabilitation.

The Human Rights movement has long demanded the Right to Housing as a necessary pre-condition for a right to life or dignity. But not only has the Right to Decent Housing not been legalised in India, in fact slum evictions and forced homelessness have mostly taken place under legal sanctions throughout the country, through court orders. According to 2017 data collected by the Housing and Land Rights Network India (HLRN), the cities of Mumbai and Navi Mumbai together accounted for a total of 22,277 households getting demolished, 18,092 out of which were for “beautification of the city” and other such reasons (Forest and Wildlife protection being the second main reason, accounting for 3,659 house demolitions). According to the report, government authorities, at both the central and state levels, demolished over 53,700 homes across the country, thereby forcefully evicting a minimum of 2.6 lakh people. HLRN finds that the highest percentage of evictions (affecting over 1,22,000 people) were carried out for ‘slum clearance’ drives, ‘slum-free city’ schemes, ‘city beautification,’ and ‘smart city’ projects.

In Navi Mumbai for example, where Mumbai metropolis is spreading to mainly in recent times, ‘slum clearance’ drives rendered over 3,300 families homeless between January and October 2017 alone. Between August and November 2017, different government agencies in Delhi, including the South Delhi Municipal Corporation and the Central Public Works Department forcefully evicted over 1,500 homeless people from under flyovers in Delhi, under the pretext of flyover ‘beautification.’ In order to ‘beautify’ areas for the Under-17 World Cup Football tournament in October 2017, the West Bengal Govt demolished 88 low-income homes and evicted 5,000 street vendors. In the same year, the state government also evicted 1,200 families for the Kolkata Book Fair. Court orders and their interpretation by state authorities were responsible for 17 per cent of the total evictions, as recorded by HLRN. Notably, the Central Government does not collect national data on the number of households evicted each year, and neither do specific states. According to the findings of a 2016 survey by Save the Children, city street children constitute 0.5 to 1.4 per cent of the population. This would mean today there are anywhere between 23 to 63 lakh children on the streets in India’s cities. Out of them, around 2.3 lakh would be in Mumbai alone.

[metaslider id=”5569″]

Proper rehabilitation and redevelopment schemes are essential for the slum and street residents to shake off their social stamp of “encroachers”, “squatters” or otherwise illegal occupants, and advance one step towards a notion of property rights and a decent and formalized citizenship. Many rehabilitated slum residents have often mentioned they felt social gaze at them change after they are rehabilitated in decent apartments. International human rights law requires that rehabilitation be in situ, in recognition of the fact that most often it will be in the best interest of slum dwellers to remain on the lands where they have been residing for extended period of time, close to where they are employed, and where their children attend school. While the courts have taken divergent views and decisions with respect to the recognition of the right to housing and have recently sanctioned numerous demolitions, the Supreme Court and several High Courts have on several occasions issued progressive judgements upholding the right to adequate housing under international human rights law. For example, in 2010 the Delhi Court released two judgments affirming Constitutional guarantee for the right to housing, noting that “adequate housing serves as the crucible for human well-being and development” and affirming that prior to an eviction, rehabilitation sites with access to infrastructure, services and amenities and a decent living must be found. The Supreme Court has also issued several important judgments affirming the right to housing. In the ‘Right to Food case’ the Supreme Court took urgent notice of the denial of the right to housing for persons living in the streets in Delhi, recognizing the threat this poses to the right to life.

In India, the lack of housing, and the prevention of access to proper housing, has historically affected disadvantaged communities more. An overwhelming majority of slum residents across the country are people belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and minority religions. Numerous studies on access to private rental accommodation in Indian cities have shown that discrimination against Muslims (as well as Dalits) is a barrier to housing access. Private landlords, real estate brokers, and property dealers often refuse to rent to someone who is Muslim, or impose unfair conditions. It is also the case that in most parts of the country Muslims are compelled to leave their homes and migrate to places where other Muslims are living, often in slums. Mortality rates are 6 or 7 times higher among the homeless than among the non-homeless populations. Women and children experience particular forms of violence in such spaces. Medical services, which are often simply denied to homeless women because of their homelessness, have a disproportionate effect on women, particularly those who are pregnant, including during child birth. Children suffer severe malnutrition. Central government authorities regularly carry out evictions in Delhi during the winter, rendering families homeless and vulnerable to the bitter cold and severe pollution. In Pul Mithai, bulldozers allegedly reached the settlement at 4 am and commenced demolition at 6 am, when people were still asleep in their homes. Even though a Maharashtra government resolution prohibits evictions during the monsoons, Baltu Bai Nagar in Navi Mumbai was demolished on 7 June 2017, leaving people out in the rain. The Tansa pipelines evictions too were conducted during the monsoon, and the evicted families had to spend weeks outside without shelter, in the rains. In Chennai, authorities evicted families before and during school examinations and also during the rainy season.

The people living in the slums are the “city makers”, providing the informal labour and services that sustains urban activity. While these circumstances provide especially for cheap and highly exploitative labour on the one hand, Governments are on the other hand clearly reluctant to provide housing, land and basic services to this population. This is in spite of specific court orders, entire ministries such as the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, and schemes like the National Urban Livelihood Mission, Indira Awas Yojana, and their more recent spin-offs like the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana, also known as “Housing for All by 2022”. Each of these schemes had come up for criticisms both in terms of their Public-Private Partnership-based business model, effectiveness and implementation. In the case of Mahul residents, the Government is refusing to provide proper livable rehabilitation even when there is a High Court order specifically asking the Government to immediately provide for the same. A total of 5,500 households currently in the Mahul SRA have demanded for proper accommodation, and the Government has told them they don’t have so many flats. On the other hand, according to the 2018 Knight-Frank report on real estate, the city of Mumbai has at present around 1,19,526 unsold flats and records a 21 per cent vacancy in flats.

After being repeatedly deceived by the political leaders and their false promises, Mahul residents have announced ‘Chalo Mantralaya’ on 15th December, when they plan to march and demonstrate in front of the State Secretariat, and demand for decent rehabilitation at the earliest. “We won’t leave the Mantralay after 15th, unless they agree to our demands,” said one of the children in the rally, while taking a short break between raising slogans.

Photos: GroundXero