Notions of purity, pollution and caste have always been embodied in food practices of Hindu society. Recent attacks on religious minorities and marginalized castes in the name of cow-vigilantism is only the newest form of historical State control over a fractured society through the politics of food and animal slaughter. The current regime’s active role in deciding dinner of a Dalit household, is not only a violation of her right to food but also a mechanism to economically fracture an already deprived section of the society. Historically tracing the shift of the Brahmin as a beef-consuming entity to his ultimate adoption of vegetarianism, Aabha Joshi discusses the exclusion of communities from Hindu society because of beef-eating practices.

“The untouchable locality would exhibit a festive mood when the news was delivered by the upper caste men that a cow/buffalo/bull has died and needed to be disposed off. The sweaty and stinking bodies could then eat to their heart’s content.”

Talking about the relationship of a Dalit community with Beef, in an auto-ethnographic paper titled, “Why was beef banished from my kitchen”, Prof. N Sukumar has exemplified the dependence of such communities on bovine meat. The Mahar (Dalit) community of Maharashtra have been engaged in the occupation of disposing the dead animal in the village for centuries. The meat from the carcass was consumed and distributed among the people of the community and some was also preserved on the roofs of the Dalit household for later consumption (Sukumar). The economically deprived Dalit had very little means to fill the hungry bellies of the family and highly depended on the carcass of the animal to nourish herself as it was the most affordable nutritional meal. This practice has also transformed with time and context.

In May 2017, the Environment Ministry under BJP led NDA Government called for a nationwide ban on sale and purchase of cattle. Popularly coined as ‘beef ban’, the ban on sale and purchase of cattle not only impinged upon the right to food, but also deprived the Dalit community one of its primary sources of nutrition and employment. The Congress too introduced law on cow-slaughter in 24 States in 1955, when the BJP wasn’t even formed. Thus, it is to be noted that the need to protect the cow is deeply entrenched in Hindu society regardless of the party in power. The Sangh today has mostly enforced such a writ with more fervour than perhaps ever seen before.

The BJP manifesto had prioritised beef ban as an agenda, labelling beef eating practice as a phenomenon that came to India with the ‘Mughal invaders’, giving it an ‘anti-India’ character, suggesting that beef is a food for Christians and Muslims – aka, the ‘outsiders’ – alone (Ilaiah, 1996). There is however more than enough historical evidence to suggest that the practice of eating beef can be traced way before the Mughal era, in fact all the way back to the Vedic period. Such a blanket ban is thus based on an erasure of history.

In today’s India, though the biggest chunk of beef eating population is Muslim by faith, according to NSSO data, beef is far from being just a “Muslim food”. While around 63.4 million Muslims consume beef/buffalo, adding up to 40% of the total Muslim population in the country, SC communities account for 12.5 million beef eaters (around 2% of the official Hindu population), occupying the second spot.

Once history has been erased from public memory and discourse, the doors for categorical violence on certain communities, and communal polarisation of the entire society are thrown wide open. The current ongoing phase of organised assaults on Muslims and Dalits, beginning with the likes of Akhlaq and 5 Dalit boys in Una, are aggressions towards communities or identities considered as ‘other’ or ‘lower’, hiding behind a mask of food vigilantism.

Recognising the dire need to understand the politics of beef and its direct implications on the Dalit, Adivasi, Bahujan and Minority communities, it becomes imperative to theoretically engage with food as a cultural practice.

History of Beef

It is a well-established fact that people belonging to today’s Dalit communities have historically engaged with the dead animal, specifically with beef (cow/bull/buffalo). They skinned it to manufacture leather wear, disposed it from the village to keep it clean, consumed the meat of the disposed animal. This very shared socio-economic relationship with beef divided the ’Broken Men’ from the Hindu society (Ambedkar, 1948). In “The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?”, Ambedkar raises an important question on whether it is the consumption of beef that makes the ‘broken men’ untouchables.

Tracing the mentions of beef in the Rig Vedas, Ambedkar proposed definite evidence to suggest that beef was consumed not just by the Hindu in general, but also by the Brahmins specifically.

In Rig Veda (X. 86.14) Indra says: “They cook for one, 15 plus twenty oxen.” The Rig Veda (X. 91.14) says that for Agni were sacrificed horses, bulls, oxen, barren cows and rams. From the Rig Veda (X. 72.6) it appears that the cow was killed with a sword or an axe…

There are religious texts that instruct which animal had to be sacrificed as offerings to God. Not only was the animal sacrificed as an offering to the deity but also offered to a Brahmin as a symbol of respect. In fact, Ambedkar in his essay, ‘Untouchability, the Dead Cow and the Brahmin’ discusses how it was considered degrading if a Brahmin was not offered beef. The practice of offering beef to the Brahmin led to such excesses that the guest came to be called as ‘Go-ghna’, which means the killer of the cow. This practice however experienced a shift over time.

The Vedas and Beef

There is abundant literature which suggests that animal sacrifice and its dietary conditions came to the sub-continent when the eastern branch of Indo-Aryans or Vedic Aryans migrated in the middle of 2000 BC. This practice continued even during the later Vedic period. The later Vedic texts provide detailed and frequent reference to cattle slaughter. DN Jha in his book the ‘Myth of the Holy Cow’ explicitly quotes the Vedas and its mentions of animal slaughter including the cow. The presented text also connotes the excesses of cattle slaughter as a frequent ritual during the Vedic period. Cattle was sacrificed during auspicious occasions. A percept of the Rigveda also refers to the use of the skin or the thick fat of the cow for covering the dead body. In Atharva Veda, the cow was burnt with the dead to guarantee a ride to the next world.

There is ample archaeological material attested with the practice of killing the cattle including the cow. Excavations from the Harappan civilisation clearly prove that cattle flesh was consumed. Relevant archaeological evidence for this claim have been found in Sindh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Kutch, Saurashtra, and coastal Gujarat. Later archaeological evidence from the first millenium BC also testify the continuity of this practice.

A trove of bones of the buffalo, sheep, goat, pig, elephant and a short-horned variety of cows of today have been excavated from Hastinapur (Meerut), ranging from 11th to the 3rd century BC. These bones showed definitive cut marks or were charred, suggesting that they were cooked and eaten. In another such archaeological discovery predated the 5th Century BC from Etah district of Uttar Pradesh, 64% of the 927 identified bone fragments were from cows, and had cut marks. The various Vedic percepts and supplemented archaeological evidence suggest strongly that it was normal practice to kill milch cattle including the cow, during the Vedic and Post-Vedic centuries. If beef eating was such an accepted practice in the revered Vedas, how is it then that Brahmins gave up beef?

Why did the Brahmins give up eating beef?

B.R. Ambedkar made an attempt to explain this phenomenon. According to him, the Hindu classes can be defined by their food practices. Hindus are either Masahari (non-vegetarian) or Shakahari (vegetarians). The class of Masaharis are further divided into i) those who eat flesh but do not eat cow flesh; ii) those who eat flesh including cow-flesh. Thus the Hindu caste society, on the basis of their food practices, can be classified as i) Vegetarians (Largely Brahmins and other upper castes); ii) those who eat flesh but not cow-flesh (Largely Non-Brahmin caste-Hindus); and iii) Those who eat flesh including cow flesh (Largely Dalits). Though slightly different from the four-fold classification of the Chaturvarna, this three-fold structure is substantial to understand the food practices in Hindu society. However it is important to understand why a generally flesh eating person would object to consuming only one kind of meat, cow meat? The explanation can be found in the Law of Asoka and the Law of Manu.

Cow in Manu

The only reference to cow in the scriptures of Manu was made in a series of instructions laid down to restrain contact of the ‘Snataka’ (Brahmin-Student Scholar) with the accessories of the cow or the cow itself.

1. A Snataka should not eat food which a cow has smelt.

2. A Snataka should not step over a rope to which a calf is tied.

3. A Snataka should not urinate in a cowpan.

4. A Snataka should not answer call of nature facing a cow.

5. A Snataka should not keep his right arm uncovered when he enters a cowpan.

6. A Snataka should not interrupt a cow which is sucking her calf, nor tell anybody of it.

7. A Snataka should not ride on the back of the cow.

8. A Snataka should not offend the cow.

9. A Snataka who is impure must not touch a cow with his hand.

Based on the above verses of Manu, Ambedkar proposed a radical position suggesting that, as great emphasis was laid on abstaining from contact with the cow, the cow was ‘not regarded as a sacred animal’. In fact it was regarded as an impure animal whose touch caused ‘ceremonial pollution’. Incidentally, Manu did not put a prohibition on cow slaughter, in fact he found it obligatory to eat cow on certain occasions. (The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables?, Ambedkar, 1948)

How then is it that the Brahmins drifted from consuming the cow and then completely adopted vegetarianism? The answers are rooted in the historical contest between Buddhism and Brahmanism.

Asoka’ Legislations prohibiting animal slaughter and the Brahman-Buddhist conflict

There are two contending arguments regarding whether Asoka banned the slaughter of the cow? On examining the legislations of Asoka, Prof. Vincent Smith seemed to express disagreement with the proposition that he did. He said: “It is noteworthy that Asoka’s rules do not forbid the slaughter of cow, which, apparently, continued to be lawful.”

Prof Radhakumud Mookerjee contends Prof. Smith by referring to ‘Edict pillar V’, that exempted all four-legged animals from killing, including the cow. However, Vincent rejected Mookerjee’s argument by stating that the reading of the Edict was wrong as it only exempted the four-footed animals which were not utilised or eaten. It was clear that Asoka had no interest in the cow. Prof. Vincent’s argument is based on the premise that Asoka mainly wished for the sanctity of all human and animal life which propelled him to prohibit unnecessarily taking the life of an animal. And a cow cannot be an animal that is not utilised or consumed. Ambedkar proposes, as a Brahmin would not easily comply to the legislative prohibition of a ‘Buddhist’ king who they perceived to be as ‘below’ them, it was unlikely that the practice of eating beef would have been altered dramatically by Asoka’s edicts. However, it is likely that the expansion of Buddhism must be regarded as one of the reason facilitating this shift over time.

If one were to take Prof. Smith’s stand, then the question of why the Brahmin gives up beef, still remains. And perhaps the next logical place to search for an answer, continuing from Asoka, is the conflict between Buddhism and Brahmanism. The Buddhist wave in the era was perceived as a looming threat to Hinduism. Buddhism was the most practiced religion at one time, and challenged Hindu orthodoxy. It was this strife between Buddhism and Hinduism which Ambedkar suggests was the reason behind the deification of the cow to maintain a moral high-ground over Buddhism. This, according to Ambedkar, is also understood to be the reason behind Brahmins’ adoption of vegetarianism.

To my mind, it was strategy which made the Brahmins

give up beef-eating and start worshipping the cow. The clue to

the worship of the cow is to be found in the struggle between

Buddhism and Brahmanism and the means adopted by

Brahmanism to establish its supremacy over Buddhism. (Ambedkar, 1948)

According to Ambedkar, deification of the cow was only one of many such tactics. He writes about how, for example, the practice of building idols and temples for Hindu Gods was an imitation of the Buddhist tradition, after the disciples of Buddha started to build Stupas and idols of their teacher. The Buddhists, in order to cling on to the same moral high ground that the Brahmans had been gaining from giving up beef, had to reorient the act of sacrificing an animal for consumption. This shift of the Buddhists forfeiting the consumption of meat has been explained by a Chinese traveller Yuan Chang in his writings. Chang observed that a wealthy General named Siha in Vaisali converted to Buddhism and offered abundant meat to the Bhikkhus. When this was brought to the notice of the Master, he summoned the brethren and pronounced a Law to renounce the consumption of meat specifically slain for consumption. However he permitted the consumption of flesh which was categorised into 3 types, based on the nature of the purpose. This came to be known as the ‘three pures’.

The Brahmin was seen as a Go-ghna and had to escape the label. They also had to secure a moral position which they claimed to be superior than the Buddhist who continued to consume meat. Thus, in order to remain as a sacrosanct entity, the Brahmin shifted to vegetarianism and while doing so defined Shakahari food as ‘pure’ while labelling the rest beef-flesh-meat and non-beef-flesh-meat as other than pure.

The Hindu Kings and their attacks on Buddhism.

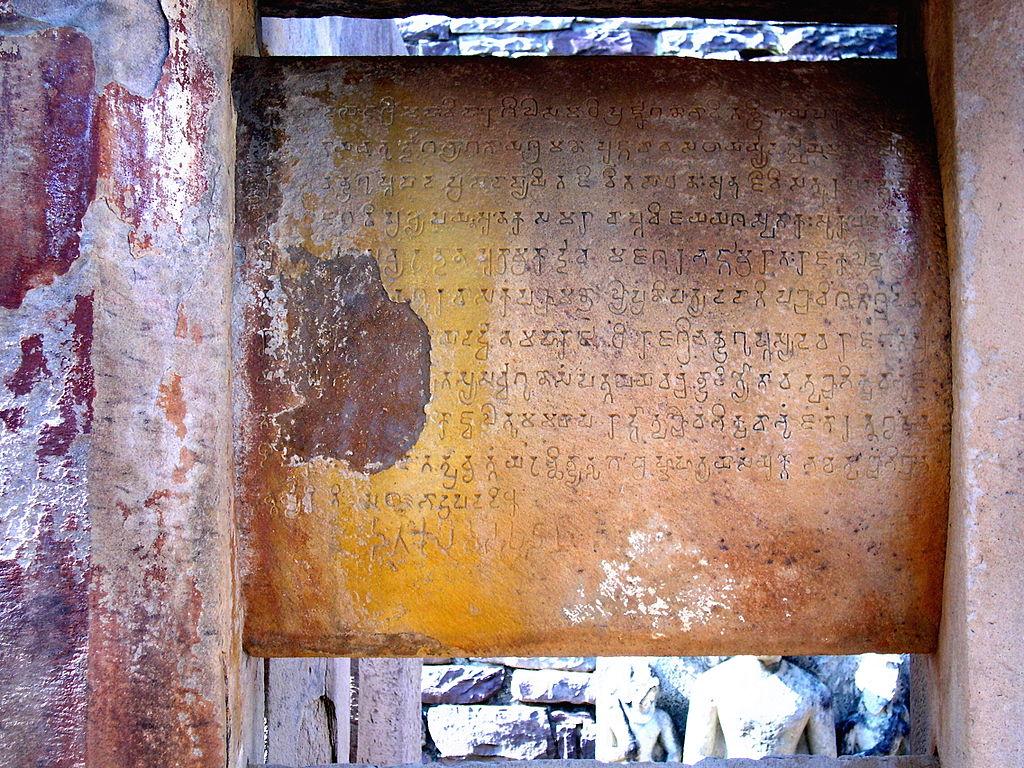

Cow killing was made a ‘Mahapataka’, a mortal sin, by the Gupta Kings who were the champions of Hinduism. D.R. Bhandarkar in his book, ‘Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (1940)’ presents evidence of inscriptions that cow-slaughter was criminalised in the 5th Century AD by the Gupta Kings. (Ambedkar, 1948)

“The act of killing a cow was an offence of deepest turpitude, turpitude involved in murdering a Brahman.”

An older inscription of 412 AD around the Buddhist stupa at Sanchi, in Central India however reads a directive on similar lines giving equal footing to the killing of a cow and the killing of a Brahmin. The need for the Hindu King to go against the Law of Manu was indeed presumed to be a tactic adopted by the Brahmins to overcome the supremacy of the Buddhist Bhikkhus. The act of inscribing such a directive around the Buddhist Stupa by going against the Vedic pronouncement should be seen as an act of antagonism against Buddhism.

The Theory of Imitation

By ‘the theory of imitation’, it is argued that the non-Brahmin caste-Hindu too gave up the consumption of beef with the expectation of experiencing the hierarchical mobility and also to progress towards attaining a mythical ‘purity’. This ‘imitation’ should have applied to the eventual Dalit communities as well. However, as the carcass disposed from the village was one of the few sources of affordable rich protein accessible to the outcastes, all the way up to the modern times, they refused to give up the consumption of beef. Besides, as Ambedkar explained, the Dalit communities did not ‘kill’ the cow but received the flesh as part of their work as sweepers. Therefore at that point in history (Gupta rule around 500 AD, when cow-slaughter began to be strictly considered as an act of profanity), it was not relevant enough whether or not the Dalit communities imitated the upper castes (who in fact ‘killed’ the cow and consumed the fresh meat earlier) in this matter or not. This on the other hand has recently added another dimension to contemporary politics around caste with the rise of several Dalit leaders. For example in 2016, the leather-work community in Gandhinagar broke into a protest, after a member of this community was beaten up by a land-owning upper caste community, because of refusing to take the carcasses of cows. Dependency of the upper caste on Dalits as cleaners of their neighbourhood was being rediscovered as a weapon that could be used against their hegemony. Such developments are, however, restricted to the present. Historically, with time, this particular food practice became yet another way of labelling a certain section of the ‘lower caste’ as untouchable.

The Politics of Beef: Today

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley flagged Article 48 (which prevents cow-slaughter) replying to the debate on lynchings and atrocities against Dalits and Muslims in the Rajya Sabha in July last year. Article 48 of the Indian Constitution reads, “The State shall endeavour to organise agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines and shall, in particular, take steps for preserving and improving the breeds, and prohibiting the slaughter, of cows and calves and other milch and draught cattle”. Article 48 has been drafted in the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) and has been used by the Hindu Right to legitimise and defend the constitutionality of cow-slaughter.

The DPSP are broad guidelines which the State have to keep in mind while formulating policy. DPSP was philosophically adopted from the Irish Constitution which emphasised that these broad guidelines would not hold any enforcement on formulating law and policy itself, but were rather reference points while formulating policy. Directive principles were adopted into the Indian Constitution with the similar intent. The first draft of the Constitution which was submitted before the Constituent Assembly in 1948 had not introduced any such prohibition on cow slaughter. The political Right of those times, basically the Hindu-Conservative rank of the Congress, however pushed for seeking protection of cow-slaughter as a fundamental right. Seth Govind Das of the Constituent Assembly demanded prohibition of cow-slaughter in the Chapter on Fundamental Rights, on par with prohibition of untouchability. Dr. Ambedkar resisted by drawing a clear distinction between animal slaughter and untouchability as the latter is violence against the human beings as opposed to violence against the cow. The debate on introducing prohibition of cow-slaughter was however not just raised from the political Right. Other than those whose agenda was to propagate majoritarianism, there were others coming from concerns about the indispensability of cattle in an agrarian economy. Ambedkar in the Constituent Assembly could not raise a strong resistance against such a demand. Under mounting political pressure, the drafting committee made a compromise by introducing Article 48 in Directive Principles, and not as a fundamental right. Pandit Thakurdas Bhargava, a wealthy Brahmin lawyer from Hisar, drafted Article 48 based on “economic and scientific grounds”. Ambedkar with much reservation accepted this amendment.

As on the one hand vegetarianism came to be accepted as a ‘Hindu’, and synonymously ‘Indian’ identity, Dalits and Muslims on the other hand have come under constant attacks on the mere suspicion of consuming, transporting or storing cow meat. BJP, political wing of RSS, has encouraged these attacks by giving complete impunity to the perpetrators of such organised mob-violence using its control over the administration and legislature. Most of the names of the accused have direct affiliations with the saffron brigade and are celebrated for their martyrdom! The Sangh has capitalised on beef politics while subjugating the marginalised sections of the society. Using beef as an object to perpetuate violence, Muslims and Dalits in the country are subjected to heinous forms of atrocities and and then victim-blamed. As reported in the Firstpost, violence in the name of cow vigilantism in 2017 was reported to have reached its worst levels since 2010.

In the first six months of 2017, 20 cow-terror attacks were reported – more than 75 percent of the 2016 figure, which was the worst year for such violence since 2010. About half the cases of cow-related violence – 32 of 63 – were from states governed by the BJP at the time; 8 were run by the Congress, and the rest by other parties, including the Samajwadi Party (Uttar Pradesh), People’s Democratic Party (Jammu & Kashmir) and Aam Aadmi Party (Delhi).

Most of those attacked by lynch mobs have been Muslims, and Dalits.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) who provide data on the consumption, production and export of beef in India have showed that by 2015, production of beef has increased to 4.4 million tonnes from 3.3 million tonnes. However, the domestic consumption merely increased to 2.2 million tonnes. Statistics from 2 years ago suggests that the income earned by the country during 2015-2016 from beef exports stood at Rs 26,682 crore and has attained the second position in global beef exports. Data from Center for Monitoring Indian Economy Data shows, under Modi’s regime beef exports have seen a growth of around 14% per year. Under the garb of protecting the cow while also creating a culture of violence around beef, BJP MLAs have been exposed of being associated with beef export and processing companies. An exclusive by NDTV brought to light how one BJP MLA was associated to not just one but 2 such companies. The documents availed by NDTV show that Sangeet Som was the director and owned 33% of stakes of Al Dua Food Processing Pvt Ltd from 2005-08 which claims to be the leading producer and exporter of halal meat from India. Beef trade is also not just a Muslim or a Dalit trade. Few of the biggest players in beef exports are Satish Saberwal of Al Kabeer Exporters Pvt. Ltd., Sunil Kapoor of Arabian Exports Pvt. Ltd., Al Noor Exports Pvt Ltd owned by Sunil Sood, etc. ‘India Untouched’, a film that discusses the existence of caste in India shows how the so-called ‘Chamaar’ (Dalit community engaged with leather) continue to work as wage labourers in leather factories, while the dominant castes own the factories.

Beefy Assertions

7 Dalit boys were flogged by cow vigilantes in June 2016 on the suspicion of slaughtering a cow in Una, Gujarat. This stirred a radical struggle against the Hindu caste order. Thousands in Gujarat pledged to not pick up the carcass of the dead animal as a counter to the imposed occupations in a caste hierarchy. 15,000 cases of caste atrocities were reported in this period of intense anti-caste agitation across the state, which together with the Patel agitation, led up to the eventual resignation of Chief Minister Anandiben Patel.

University spaces too exploded with discourses on the Right to Food. Osmania University organised a beef festival in 2015 and cooked and distributed beef in the hostels. The police later raided the hostels and detained 30 students for display and consumption of beef in public. Some students in JNU were slapped with suspension. In protest they went on an indefinite hunger strike in campus, opposing brahmanical state violence and impingement on the right to food through Beef Ban.

This is nothing (but) brahmanization of nation. Instead, we are fighting for subalter-nization and dalit-ization of nation. (JNU Pamphlet, 2012)

In response to the beef and pork ban in the TISS canteen, some students from TISS made a film ‘Caste on the Menu Card’ which explored the notions of purity and pollution associated with the consumption of beef. (Arahana et. al)

Dalit poets recounted their relationship with beef and bespeak of their agonised and parched bellies. ‘Guest’, a poem written by Shreekrishna Kalamb projected how the Dalit shares the most intimate relationship with beef but rarely does he exercise any ownership over the cattle whose rights are unjustly monopolised by the upper-caste.

“We are calves, dumb hungry calves

we tend to the cows, thieves walk away with milk and cream

we sweat and sweat on the fields

we cultivate pearls, but our children remain hungry”

– Shreekrishna Kalamb

The author is a political activist and a researcher. Photos are courtesy author.

Very well written article, aabha you have done a really great job of highlighting the problems our country is facing and in detail. keep doing the good work.