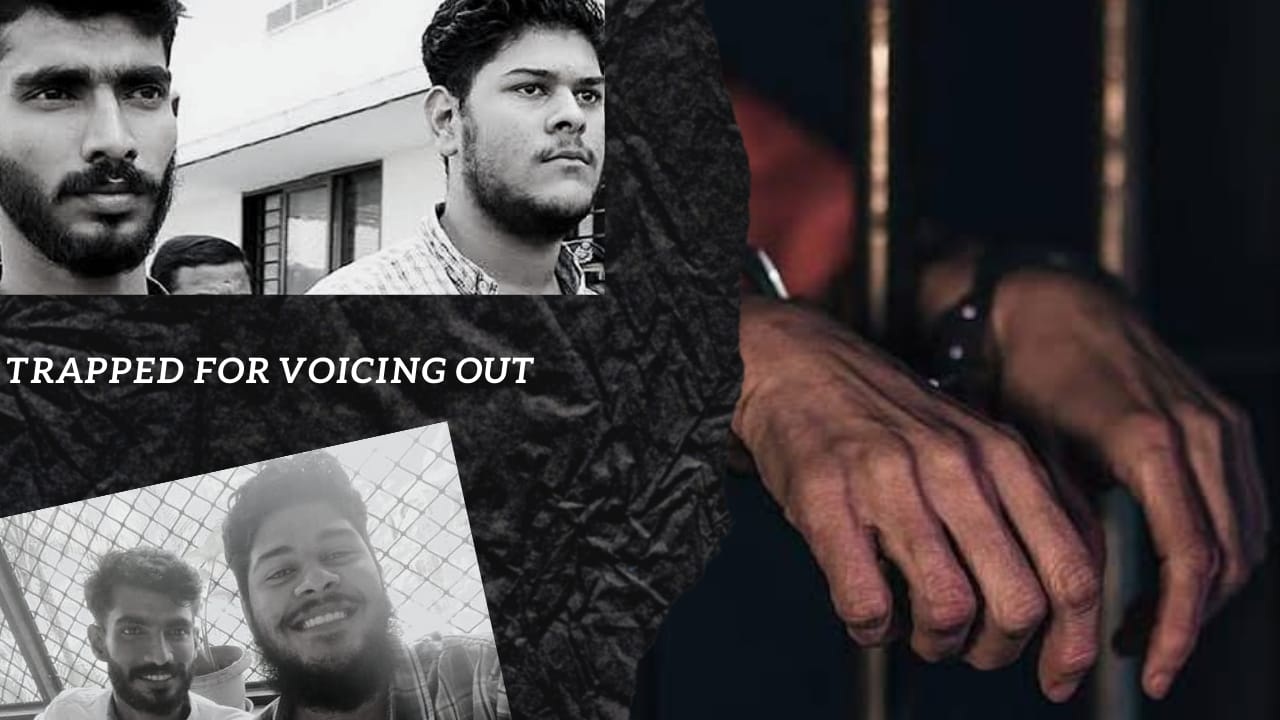

Allan Shuhaib, a 22-year old student of LLB from Kannur University, has been an active participant in various student movements in Kerala. Thwaha Fasal, 26 year old student of Rural Development from IGNOU, has worked along with his comrade, Allan, for several years. They have always been vocal about State atrocities, student concerns and the issue of the release of political prisoners. The two student activists worked and organised for the demand of the rights of the marginalised communities.

Allan spent 10 months, while Thwaha spent 20 months in jail for a 2019 case. They were both arrested for possessing and distributing literature of the banned Maoist party and charged under the draconian UAPA. GroundXero talked to the two former-SFI (Student Federation of India) members about their experiences in SFI, the Kerala Model of governance and the condition of political prisoners in Kerala.

GX: Please tell us a little bit about your family and educational backgrounds. How did you come to join student politics?

Allan: I come from a middle class family in Kozhikode, and live with my mother, father and a brother. My mother works as a teacher, and she is also an active member of the CPIM’s teacher wing. My father was an active CPIM member for twenty-five years, but now he is an RMPI worker. And, my brother has completed his degree and secured a job. I’m currently enrolled in a LLB course in Kannur University. I was an active member of SFI (Students’ Federation of India), Balasangam (Children’s wing of CPM), DYFI and CPM. Because of my family background, I began to associate with the politics of SFI and Balasangam quite early on in life. Over time, when I was studying in Class 10, I was made one of the unit secretaries in SFI. At the beginning of my tenure as an unit secretary, SFI led a strike against unruly bus drivers, who misbehaved with passengers. Its eventual victory marked the beginning of my activism.

Thaha: I stay with my father, my mother and a brother. I come from a working class family. My father worked as a daily wage labourer, while my mother has a small knitting business. Whereas, my brother has completed his degree, he is still unemployed, and is eagerly looking for a job. My entire family is associated with CPIM. I completed my honours degree in Geography from Calicut University and am currently pursuing my masters’ degree in Rural Development through IGNOU. The omnipresent CPIM heritage of my family had pushed me to become a DYFI member, and eventually a CPIM worker. I worked as a unit secretary, then as president of DYFI. Gradually, I got linked actively with CPIM, as well.

GX: Both of you were members of the CPI(M) in Kozhikode. Following the stream of events in your lives, there must have been political differences with CPI(M)? What were those differences?

Allan: We were not silent spectators, accepting everything happening in CPIM. We voiced our critique against their stand on UAPA, fake encounters and several other issues inside the committee meetings. Mostly, they kept silent, because they were unable to answer, or simply did not care to provide a response. We hold faith in the teachings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Mao, who taught communists to critically analyse any problem, even to understand the fundamentals of Communism, itself. The five masters taught us to criticise others for their political development and accept self-criticisms to learn and grow.

Thaha: I have always been critical of the CPM politics, and their anti-people policies. Their stand on UAPA, their take on fake encounter killings, custody killings, and their double standard when in power and when in opposition, amongst others have always been subjects which I couldn’t help but criticise. A communist should use the analytical tool of criticism and self-criticism properly. In most situations, I always wondered, if the ideals of Communism and CPIM’s stand ever had a link!

GX: Were those differences the reasons for your arrest? Were you ever show-caused or just expelled from the CPI(M)?

Allan: I don’t believe so, but it can’t be completely neglected as well. Both of us were expelled , following our arrest, directly by the state secretary and politburo member of CPIM, Kodiyeri Balakrishnan.

Thaha: They just kicked us out without asking for an explanation whatsoever.

GX: CPI (M)’s “Kerala Model” has become a widely-discussed issue across the nation. Along with the parliamentary left, a section of the liberals, too, are propagating the remarkable achievements of the “Kerala Model.” What, are your experiences of this Kerala Model?

Allan: I was put in jail when I was 20 years old. I have spent 10 months in three different jails, and will have to answer this with practical experiences. The image created by the Kerala model is completely false. Kerala’s prisons are filled with numerous cases of human rights violations, arrests under UAPA charges and fake encounters are frequent. The state government is hellbound to please the NDA government at Delhi, the PM Narendra Modi and home minister Amit Shah. People are mercilessly witch-hunted because of their political orientation. They say casteism is never a problem here, but I witnessed it everywhere around me. People are being discriminated against, for their economic and family backgrounds. Everything is just kept under a veil.

Thaha: Nelson Mandela once said that, ‘without spending time in jail, a person can’t understand a nation.’ We saw for ourselves how people were mistreated here in jails. I have spent 2 terms of over 20 months in 3 different jails, mostly in high security prisons in Viyyur. Atrocities against inmates and charges of fake cases have become a common scenario in prisons today.

If there had been any socio-economic progress in Kerala, that has been purely because of people moving outside the state to work, sending in remittances and the social reform movements. CPIM claims to have resolved the land crisis by introducing the land reforms. But the process of land reforms was never completed. A vast majority of working labourers and adivasis never really got their fair share of land, and are still struggling. It was more a political propaganda, in my opinion.

GX: Do you think that the parliamentary left, including the CPI(M) can play a positive role right now against the BJP-led government at the centre?

Allan: There is a serious doubt whether they can ever form a political alternative to the fascist RSS led BJP. Leaders like Yechury have addressed the nation, speaking of CPIM’s alternative form of governance and secular politics. But they have used tactics, very similar to Modi’s, in places where they are in power. Even during the left rule in Bengal, CPIM witch-hunted political activists because of their (different) political orientation, and such practices have continued in the CPM-led LDF government in Kerala. The first UAPA case was commissioned in 2007. This is a clear case of double standard. Many youths and activists have lost their lives, owing to their policies. Congress-led UDF was never really different from it, either.

Thaha: This is what CPIM leaders, all over India, claim. But, the real picture stands visibly different. In places where they are in power, CPIM’s policies coincide with the BJP politics. Be it UAPA, fake encounters, mass killings, what they preach and what they practise stand at polar opposites.

GX: How do you look upon the left student/youth movements of our times?

Allan: Students and youths have always played a crucial role in organising mass movements. Be it the Indian freedom struggle, or the anti-Emergency movement, or the recent anti-CAA protests, the student and the youth activists have always been the backbone of these struggles. The political atmosphere was much different, when we were arrested on 1st November, 2019 and were subsequently jailed. The CAA protests had brought a new group of student activists to the forefront. New discourses have unravelled. The entire Indian political situation changed after the CAA protests. We read about it, and also came to learn a lot from the protestors jailed for their significant participation in the anti-CAA movement. It was really disheartening that we could not organise anything significant at that time as we were inside prison.

“The world around us was burning.

We woke up hearing slogans, we were voiceless.

But never hopeless.”

Thaha: Students and youth have been an essential element of any mass movements around the world. It was also the case in anti-CAA and the recent farmers’ upsurge. Also, women’s leadership in the anti-CAA protests was something inspiring to view.

GX: Governments have almost always termed political prisoners as “terrorists”. What has been your experience with the CPI(M) led govt. in Kerala, given that the Chief Minister openly claimed that you are Maoists? What were the reasons for making such a statement?”

Allan: I second your observation completely. Governments have always termed political prisoners as ‘terrorists’. Be it the British, the subsequent Congress, BJP or CPIM, they all speak the same language. I believe such language comprises the structure of the state itself. While the British tagged Bhagat Singh, Congress government called communists terrorists, and the BJP tags everyone in the opposition as ‘anti-national’. Basically, the state uses this strategy to curb any form of dissent, isolate those dissenting from the society. Unfortunately, or fortunately, their ‘terrorists’, won’t be the same for the wider mass. Unfortunately, or fortunately for us, the people whom they brand as “terrorists” are not seen as such by the wider masses.

Thaha: In our case also, CPIM and the Kerala Chief Minister, Pinarayi Vijayan tried to brand us as “terrorists.” They declared it publicly and championed their view in our locality and campuses. But sadly, their attempts turned futile. Because people from different streams supported us, and unmasked the CPIM stand completely. Later the judiciary’s verdict also does not linked our work to terrorist activities or any banned outfit.

GX: Why were you arrested? What were the charges? Were you arrested under UAPA? Or, was it imposed later on?

Allan : Originally it was a UAPA case, registered under sections 20, 38, and 39 in Pantheerankavu police station. Later, in December, the NIA took over this case. When the NIA filed the charge-sheet, section 20 was dropped. And IPC 120B was added. Section 13 of UAPA was charged against Thaha. The third accused, Usman had been absconding, and was later arrested. Another person, Vijith, was also arrested as the 4th accused.

Thaha: The State has always tried to curb dissent, and put people with different opinions in jails. They portrayed them as ‘terrorists’ to wipe out the mass support that they garnered. The Chief Minister made such a comment. When a case was under investigation, such a remark should not have been made.

GX: Can you tell us a little bit about the solidarity and support that you received from different quarters?

Allan: The solidarity we received, really surprised us. It was really important and kept our spirits high inside the jail. A committee was formed for our release, with the famous journalist BRP Bhasker as its chairman. Most such cases in the past ended up in the inside pages of the newspapers, and people rarely remembered or talked about them. But that did not happen to us.

But, at the same time, we were deeply saddened that our co-accused, Vijith and Usman, did not get such support. The supporters were selective, and extended solidarity to us for their own personal gains. Some of these people even tried to pressure me, and to transform me into an approver. UAPA was also a problem for the CPIM, when their leaders, P Jayarajan and others were accused in the Kathiroor Manoj Case. But many CPIM workers supported us within their limits. In our opinion, such support should be extended to all UAPA and political prisoners.

Thaha : We received support from different stratas of the society. Many politicians, lawyers, media persons and many others expressed their solidarity. But it breaks my heart to see, such solidarity never gets extended to other political prisoners.

GX: How long were you in prison? When were you released on bail? What are the bail conditions or restrictions?

Allan: We both were in prison for 10 months. The NIA court in Kochi granted us bail on September 11, 2020. But after three months, the Kerala High Court dismissed Thaha’s bail. He appealed in the Supreme Court. His bail was approved by the Supreme Court in November, 2021. So he was forced to spend another ten months in prison, making it a total of 20 months in custody. After our release, we have to give attendance at the local police station on every first Saturday of the month, and are not allowed to move out of the city. These are some of the major restrictions within which we now lead our lives.

GX: The question of the rights of the political prisoners in jail has emerged as a serious one in India, in the last few years, especially after the Bhima-Koregaon case. Can you please tell us a little bit about your thoughts on the issue, contextualising them with your own experiences?

Allan: This is a very important question. One thing we must keep in mind is that most reforms in jails were not gifts from the state, but were the results of frequent, long-drawn struggles of the political prisoners. As you said, the Bhima-Koregaon case has to be the benchmark regarding the issue of political prisoners in present India. We are all aware how everyone is being treated. When prisoners, like Stan Swamy, who only asked for a mere straw, but was refused, and the conditions were worsened for him, we have to see this as an instance where a political prisoner has basically been let to die inside the custody. Sudha Bharadwaj, after getting bail, in all of her interviews, has highlighted the situations inside the jail which she and her co-accused were forced to live in. On top of that, she has also spoken at length about the struggles she has faced as a women prisoner. The situation in the prisons in India has gotten far worse after the pandemic.

In Kerala, the situation seems different from the outside, but inside the custody, human rights violations have been a common scenario, and people are constantly indulging in protests against it.

Maoist leader Roopesh has taken part in numerous legal battles and hunger strikes. Danish, Rajeevan and other prisoners are also continuing their fight for basic rights inside the prison. The protests were against the 24 hour illegal solitary confinement in the name of quarantine, to arrange for soaps to wash hands, to get COVID tests of inmates done, against illegal naked body checks, amongst other concerns. Whereas, the CPIM government led by Pinarayi Vijayan is just turning away its eyes from addressing such issues. They made the situation worse for Comrade Ibrahim. He is 63 now, lodged in jail. The High Court had granted bail to him on medical grounds. He was with us in Viyyur High Security prison. They cry over Stan Swamy’s death, but did not pursue Ibrahim’s release. This is a case of pure hypocrisy.

Kerala, unlike other states, has no provision of legal status for political prisoners. This made the protestors and mass leaders, ‘terrorists’ and ‘anti-socials’. There should be a move to sanction the status of persons arrested for their political beliefs. At a time when activists are being witch-hunted, we should take up this issue of political prisoners, seriously.

Thaha: The political prisoners face regular harassment inside the jail. I, myself, had to approach the Court for my dental treatment multiple times. When we were in Kakkanad District Jail, during the time of the Corona, the Jail Superintendent said, ‘What’s for us if you get infected?’

They filed another case against us when we complained about the bad behaviour and the overall situation prevailing inside the jail. Imagine, during the time of the pandemic, the political prisoners are locked inside their cells for 24 hours, or even for months in the name of social isolation. They are being denied newspapers, books and even underwear, just to worsen the situation for them. This is not the exclusive case of Kerala, but this is happening all over India. The goal is to damage the political prisoners physically and mentally. The situation inside the jails is just like what it was in the beginning of the 20th century. They are denying the basic rights to the prisoners to study and write. It should be highly condemned that a state like Kerala, with a history of struggles, and a long list of political prisoners organising and protesting for the betterment of the situation, has still no provisions for the legal status of “political prisoner.” More voices should be raised for their release and basic human rights.

GX: Although the question of the release of political prisoners has become an important issue in our nation-wide debates, we haven’t yet witnessed the emergence of a nation-wide movement demanding their release. What, according to you, are the reasons for the absence of such a movement?

Allan: That’s only partially true, as organisations like CRPP (Committee for Release of Political Prisoners) have their roots in most of the states. But yes, there have been a lot of setbacks and drawbacks, faced by the movement. The main problem has been, how does one identify a political prisoner. What is the definition of a political prisoner? Who is a political prisoner? There are still various loopholes in understanding the term. This prevents the development of a united front in this regard. But, things are changing. People have started recognizing the importance of the question of the prisoners’ release. In the farmers’ protest, fortunately one of their demands was the release of the political prisoners. We are hoping for a positive change in this regard.

Thaha: A proper movement has still not been organised on this question, despite the organisation’s [CRPP] presence in various states. The state in return, is also lodging UAPA charges against people standing for the issue of political prisoners. Social workers, student leaders, human rights activists, environmental activists are all being put in jail and people who work for their release, are also getting targeted by the state. The terror unleashed through such an environment of witch-hunting, is breaking the scope of any development of democratic and human rights movement. Yet, these policies are also being discussed around the nation. We hope through the initiation of such discourses, movements too might set in soon.

GX: What are the primary fields and issues where the leftist student movements should devote their attention right now?

Allan- Definitely, attention should be devoted to organising against the ongoing attacks of the fascist regime and to bring about social changes. In campuses, there is a huge tendency of ‘depoliticisation’. Organisations like SFI and NSU have their own political limits in addressing such issues. They have never really taken any thought-provoking initiatives, and end up celebrating Valentine’s Day on campuses.

In my campus, at the off-campus of Kannur university, SFI thrashed a first year LLB student for not being a part of their organisation. Though he was not a member of any organisation, he was accused of being a member of KSU. Protest meetings were organised by us to condemn such an action. SFI issued a collective threat. The Kerala wing of KSU, NSU, are also ruling the campus like fascists, and they also genuinely lack the political and creative minds to initiate new political programmes. There is an urgent need of reconsidering such tactics through proper criticism and self-criticism initiatives.

Thaha: When the country is under a fascist rule, the primary motive is to struggle against them.

GX: As such, there are very few documentary stories about the conditions of the jails in Kerala. Can you speak a little bit about them? What were your experiences inside the jail like?

Allan: Very few commercial movies have depicted reality. The conditions inside are terrible. Thousands are suffering everyday. The pandemic has worsened the condition as well. I was locked in a cell, very small and suffocating. We had to bend our backs, head and toe, to not hit the walls. We were denied the basic human needs. It feels amusing to note, a state bragging about its history of revolution and struggles, has kept their prisoners in such a poor condition. Definitely, a state should be judged by the conditions of their prisoners. It’s a test, where all the political fallacies ultimately play out.

Thaha: Prisons in Kerala deliberately rip off the basic human rights. News and writings in papers and media depict it as a piece of heaven, but the reality broke down when I went inside. In the high security prison where I spent 20 months, regular abuse and false cases against prisoners were common. People with health issues are not given adequate treatment. After complaints, the treatment was conducted, but then again, the medicines were delayed. For petty reasons, they lock you up inside the cell 24/7. Denying newspapers and books was also quite common. Even today, Indian jails function as feudal machineries. Amidst such discourses on prisons, and a growing consciousness nationwide, Kerala still trips backward in this regard, and would not quite hit the mark.

GX: How were the ordinary prisoners treated during Covid in Kerala? Were any special arrangements made during the time? What have been your experiences of the pandemic inside the prison?

Allan: Our privileged status of political prisoners, had made people talk about us a lot. But most ordinary prisoners were from poor backgrounds, and no one came to look after their welfare. Prison officials did certain things for them as charity, but not as their right. Medical treatment was very bad in times of corona. They didn’t let prisoners have regular check-ups in medical colleges because of corona, and the overall quality of the health of the prisoners deteriorated. It was a really depressing time. Overall, most prisoners and wardens were depressed. There was uncertainty at its peak.

Thaha- Covid times have added more misery to the lives of prisoners. Instead of making special arrangements available to them, they have been locked inside their cells for the entire day. Their claim of providing nutritious food to the prisoners is only a partial truth. Almost five to ten prison officers used to raid a single cell during the course of a day, which has been locked for twenty four hours, without even wearing masks or maintaining social distance. This has contributed to the spread of the virus in the cells. During this time, the prisoners were neither allowed to give any interview or make any calls. They were also denied access to books and newspapers. All in all, this pandemic has made the lives of prisoners hellish.

GX: Did you face any social stigma of being labelled a “terrorist”? If yes, how are you dealing with it?

Allan: Besides the government, some CPIM and RSS workers, most of the people around us accepted us as who we are. It wasn’t a big problem for us compared to other people accused in such cases. We received lots of support. People welcomed us wherever we went. But fearing the witch-hunt that the state might put them through, many of my friends have left me. I even had a break up with my girlfriend, soon after my release, just because of this case. But while some people left us, many more people have come forward. They have accepted us as who we are, without fear.

Thaha: Apart from the government, the society at large didn’t brand us in that way. A lot of people stood up for us. The feeling that we are not alone gave us the energy to move forward. In the case of the political prisoners, the fact that people stand with them, gives them mental and political energy

GX: What are your future plans?

Allan: I’m planning to complete my LLB degree, and start practising law soon after finishing up. My aim is to fight for the release of all political prisoners intensely. I am also planning to write on my experiences of being a political prisoner.

Thaha: I’m planning to go forward with my education. But I will continue to take a firm stand against draconian laws like UAPA and will continue to advocate for the release of all political prisoners.

In solidarity with and in unflinching support for the release of Political Prisoners. ✊?