The prominent Hindi and Bangla writer and translator Kanchan Kumar passed away in Kolkata on 28thNovember, 2025. Born in Birudiha (Bardhaman district, then in undivided Bengal) in 1936, he grew up in Banaras and had already gained recognition as an emerging Hindi writer by the 1960s, working across multiple genres. His life and work took new turns after the 1967 uprising in Naxalbari which he was inspired by, and he worked primarily as a Hindi translator and essayist from the 1970s onwards, while publishing and editing works in multiple languages. Since the early 2000s he translated prolifically into Bangla. He was also centrally involved with many significant organisational efforts over the years, such as with the formation of the All India League for Revolutionary Culture.

Here Abhishek Bhattacharyya writes a short obituary, which is followed by an extended excerpt from a previously unpublished 2015 interview with Kanchan Kumar, where he discusses his upbringing and early publications –bringing alive the Bangla and Hindi literary worlds from the late colonial period into the late 1960s. Some photographs of archival documents are included.

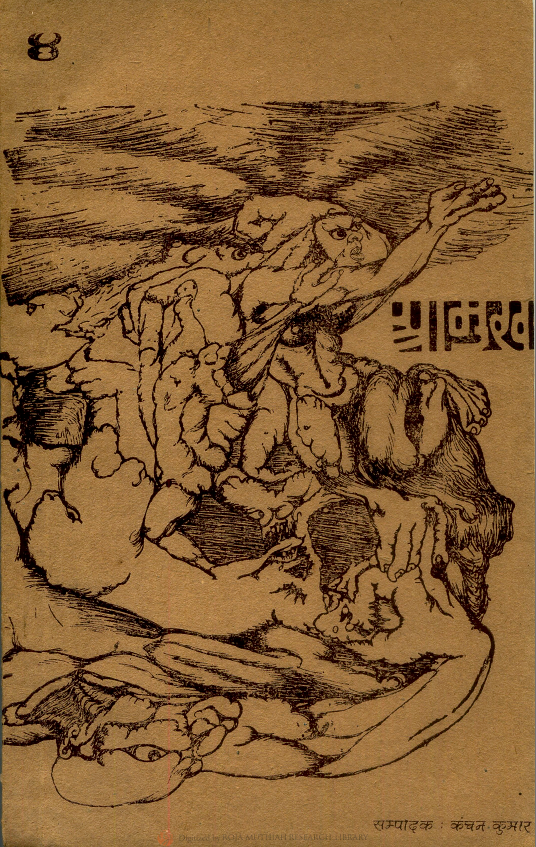

Issue 4 of “Amukh,” probably 1966, cover art: Anil Karanjai.

I first learnt of the Hindi little magazine Amukh (Preface) while travelling through Maharashtra and erstwhile Andhra Pradesh in 2013, in preparation for my doctoral research. I was looking to study the history of the left since Naxalbari and wanted to know more about cultural productions associated with the movement in different parts of the country. In enquiring about the possibility of finding translations in any of the languages I then read, the name of one Hindi magazine came up in different places: Amukh. Started in Banaras in 1965, after 1967 the magazine took a new turn, and through its various journeys, via Delhi and other places, till 2004, it published contemporaneous translations of revolutionary literature from across the country. I located the entire Amukhcollection with Kanchan Kumar later that year in Kolkata, where he had been living for the past decade. While Amukh always had a rotating cast of editors, he was the one constant figure throughout its run. As I realised in starting to work with the Amukh archive, its forty-five issues likely comprise the largest contemporaneous cross-regional collection of radical left literature from late twentieth century India. Whether it was Gaddar in Telugu[i], Vilas Ghogre[ii] in Marathi, or Laal Singh Dil[iii] in Punjabi – Amukh would be translating their work into Hindi very soon within their original composition.

For my doctoral research I tried to address the question: how was it that this magazine from Banaras (and later Delhi) came to translate this diverse array of leftist voices (going far beyond any sectarian limits), and how do we understand the trends therein? Further, how did it work as an organisational tool, especially as it became the Hindi mouthpiece of the All India League for Revolutionary Culture (a broad platform for revolutionary voices, which included participation from various Naxalite parties and affiliated individuals, as well as people from other political backgrounds, such as Anand Patwardhan or Mahasweta Devi) since 1993? I will not go into that story here, and into Kanchan Kumar’s crucial role in it. Ever since he passed away on 28th November, there has been an outpouring on social media from his long-time comrades, in various languages (I’ve read several in Hindi, Bangla and Telugu, which are the languages I follow). A three page long obituary in Aruna Tara (Red Star, Vol 3, Issue 5, December 2025) by the prominent Telugu poet Varavara Rao – they were frequent collaborators – has been the most detailed account I have come across this past month. I am told some of his comrades and well-wishers will publish a book in his memory soon, and that there will be a memorial event in Kolkata. It is heartening to see this outpouring of public attention to his work, given his lifetime’s work of self-erasure. While Amukh had started as a modernist project, after 1967 it increasingly shifted focus to translating works by subaltern authors. Kanchan Kumar, who was already a prolific author in his early thirties by that time, decided to keep his own writing aside for the most part, and focussed on translating others who he felt had more revolutionary experience. Acknowledging his own privileged background as a man from a well-off upper caste family, he fashioned himself as a translator for most of his adult life.

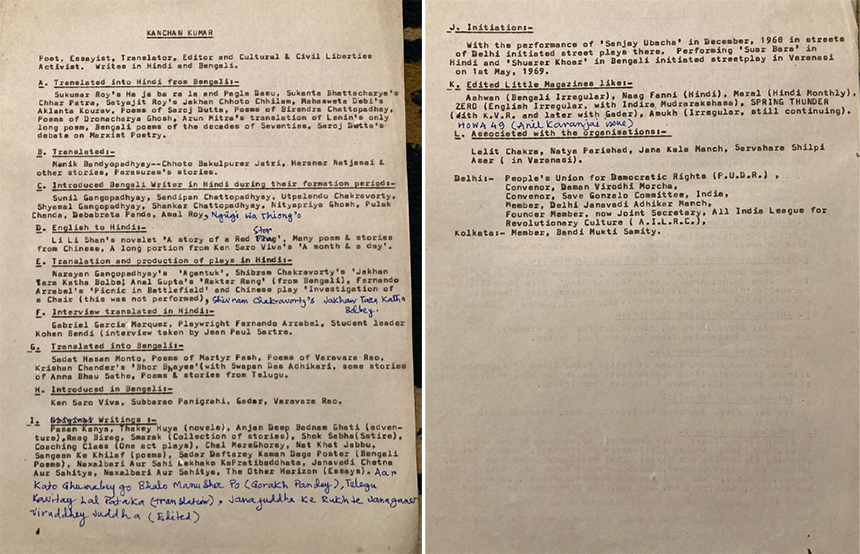

An old CV Kanchan Kumar had shared with me at some point, which highlights some of his work.

For this publication in his memory, I want to share an English translation of an interview I conducted with him in Bangla and Hindi in 2015. The interview is divided into three sections, dealing first with his childhood, then his early writing and politics, and finally the first phase of Amukh. This was meant to be published to publicise the digitisation of the magazine’s archive (for which I had received a grant from the Centre for Research Libraries, in collaboration with the University of Chicago Librarian, Laura Ring, and the digitisation was carried out by Roja Muthiah Research Library, Chennai – the full archive can be freely accessed here: https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/30315), and Kanchan Kumar had corrected the proofs for both the Bangla and English transcripts.Unfortunately, neither could be published for various reasons. Since then, with the help of UChicago, RMRL and CRL a couple of hundred books he was involved with (as editor, translator, author, or publisher), in various languages, have been digitised, and are freely available through the same website. I am sharing below the 2015 interview, with some minor amendments to account for the changed times.

While I have been writing and lecturing about his work for a while now, writing this obituary feels hard. As I draft this during my winter break in Kolkata, it is my first Kolkata visit in maybe a decade when I won’t be paying him a visit. From 2013 when I started reading Amukh, and especially during my fieldwork years of 2017-2019 as I discussed them extensively with him, I have learnt immensely from his approach to literature and politics, and have especially valued his emphasis on the importance of translation into South Asian languages. Despite our political differences, and perhaps in part because of them, our conversations have been very generative, at least for me. And I have learnt from his approach to writing the value of living a committed and disciplined life. Until glaucoma started making reading difficult in recent years, whenever I visited him during the daytime I would find him writing. Even in his early 80s he was publishing two books (of new translations by him) per year on average, until the pandemic disrupted the little magazine economy and the flow of people visiting him.

The pandemic was a difficult experience for him, primarily due to the near total social isolation it entailed. The lower back injury sustained from a police lathi charge in Delhi decades earlier did not help, especially in these times marked by increased sitting and less going out. In 2024 he was diagnosed with prostrate cancer, but responded remarkably well to treatment, and his PSA levels had been back within the normal range for the past year. However, his haemoglobin levels were repeatedly dropping this past year and half – for which he received a number of blood transfusions, but the cause for which remained undiagnosed despite various tests and scans at the hospital. Within a couple of weeks of my return to New York for the start of this academic year, in early September 2025 Kanchan Da fell down in the toilet and suffered several fractures. The medical details here onwards are a bit hazy for me as I was away. I talked with him on the phone a few times these past couple of months, but his speaking was not very clear, perhaps due to medication.

As I was feeling rather low on hearing of his death, in a vulnerable moment I mused aloud to a comrade that in these generally bleak times it is tempting to think of his death as a metaphor for the passing of a kind of political horizon. But as she aptly remarked, this can hardly be a lesson one learns from Kanchan Da, and she reminded me of an experience from earlier in the year. I had started reading aloud some short stories to him, from a new book published by Virasam (Revolutionary Writers Association). Titled Viyukka: The Morning Star[iv], it was an English translation of Telugu stories by women involved in revolutionary struggle, who mostly hailed from very marginal and usually adivasi backgrounds. He was moved to tears on hearing the stories, and was looking forward to listening to the rest during my December visit. In the meantime, even as he sat in hospital, he tried to plug this book to this comrade, suggesting that she work on translating and sharing some of the stories. In other words, even with failing health and at almost 90 years of age, he knew his work was to translate the emerging literature from the marginalised who are engaged in struggle – so being in a hospital was not a moment for despondency, but a circumstance that allowed him to meet people and seek new possibilities. While I include below an interview about his early life, I want to emphasise that rather than canonising him, the bigger tribute to his legacy would be to focus on reading and translating literature arising from people’s struggles.

A young Kanchan Kumar in an undated photo in Delhi, shared by him.

A: I’ll begin by reading some of your words from an earlier time. In the first issue of the magazine Amukh (Preface), that all of you started in 1965, you have written the following about the role of a writer:

“A writer has to discover anew the total reality of experience, and not simply that of language, form and style. This tireless surpassing [of oneself] is the primary feature of modern writing, its ultimate criterion. For that reason modern writing is necessarily self-reflexive, and to understand it, it is necessary to learn about the writer as well.”

Keeping your words in mind, I’ll start by asking some questions about your childhood.

Childhood and early influences

A: Where were you born?

K: I was born in a village called Birudiha, in the district of Bardhaman [presently in West Bengal]. This village is on the Grand Trunk road, between Panagarh and Rajbandh. … Firstly, you could describe my family as middle-class … Also I couldn’t stay in the village for too long, so it’s not like I have much early experience of village life. I left for Varanasi at a very early age. The village I was a resident of, it was very badly afflicted by malaria. At one point, both of my younger brothers and myself acquired the disease. So the doctor advised going out of town. Father took us to Varanasi. And this change was truly good for our health. Plus my father also grew attached to the city. Hence we started staying there. (However father returned to Bud Bud (in Bardhaman).

A: How old would you have been at that point?

K: About 5 or 6 [years old] Actually when my father died, in 1944, I was 8 years old. So I was born on 23rdOctober, 1936. …

A: What were your parents’ occupations?

K: My father was a poet …

A: Writing in Bangla?

K: Yes, in Bangla. And he was a good poet. (“On my father’s death, the editor of Bharotborsho, Fonindranath Mukhopadhyay, wrote an article in the weekly Sanhati, titled “Charon kobi Kanak Bhushan Mukhopadhyay” (Author of Eulogies, poet Kanak Bhushan Mukhopadhyay))[v] He was very inspired by Rabindranath Tagore’s style of writing, and would write within a tendency that traced its lineage from him.

A: So you grew up in a literary ambience?

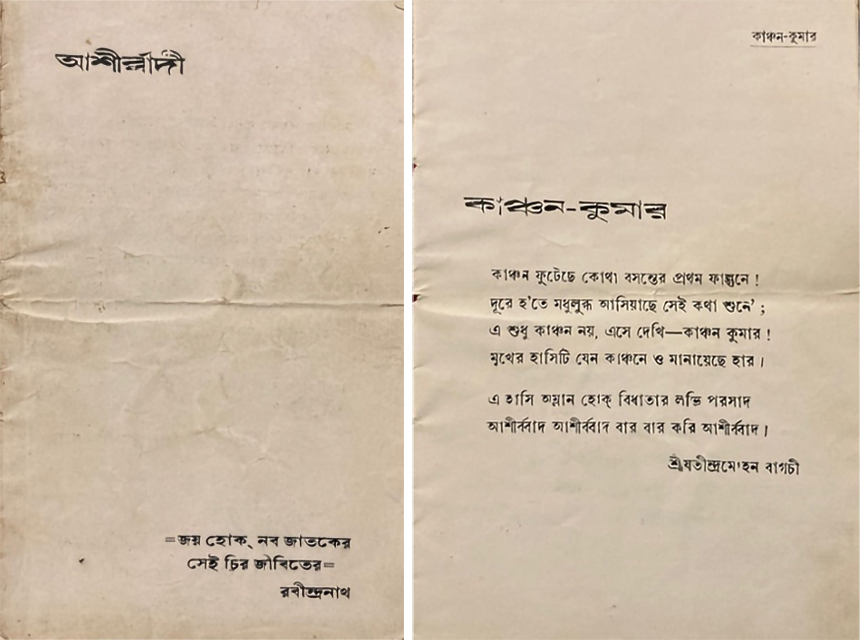

K: Yes, the ambience was there. But I couldn’t experience it so well because my father passed away while I was very young, and also because we were staying in a different place where we were very removed from their language and culture. Yet there were family connections to the realm of culture. So for example during the marriage and other occasions in the life of a first cousin on my mother’s side, or when I was given my name, Rabindranath sent his blessings. Rabindranath sent a line: “Joy Hok Nobojatoker Shei Chirojibiter” (Victory to the newly born, the immortal one); poets would send poems like that.[vi]

A: Rabindranath sent his blessings for you?

K: Yes, that one (shows me the line that Tagore sent, which he had kept carefully).

A: That means your father knew Rabindranath?

K: Not only Rabindranath, many poets … Many poets would send their blessings. That is, in the booklet that was published on the occasion of giving me a name, they had written. [Among the different people who wrote in the pamphlet were Kumud Ranjan Mallick, Kalidas Ray, Uday Chandra Mahato (King of Bardhaman), Bijoyproshad Sinha Ray, Hemchandra Bagchi, Kamla Devi, Leela Devi, Jatindra Mohan Bagchi, Radharani Devi, Narendra Dev] And in the booklet published on the occasion of the marriage of a first cousin on the maternal side, you will find the names of many familiar poets of that time. [Ashalata Devi, Annapurna Devi, Kader Nawaj, Fonindronath Mukhopadhyay, Kamakshi Prasad Chattopadhyay and many others, including most of those who wrote for Mr. Kumar] This kind of thing used to happen then. Kazi Nazrul Islam[vii] had come to our house. I have heard that Shailajananda Mukherjee[viii] was a good friend of my father’s. Among actors, there was Kamal Mitra[ix] … But we experienced none of this, because at a very early age, before we could understand anything …

L: Cover page of the booklet published on his birth, with the cover featuring the line by Tagore. R: The photo is of one of the poems in the booklet.

A: Do you have any childhood memories of any of them coming to your house, or anything like that?

K: No. Not at all. I didn’t know anyone. I used to see very little of my father, he stayed first in Bardhaman, and then Bud Bud.

A: Where is your father from?

K: From Birudiha itself. Alongside being a poet he was a very good singer as well.

A: He spent most of his life there?

K: … He used to work in Bardhaman town for a while. Later he would handle contracts for the military. As a result he moved to Bud Bud. … They put him up at the military camp there. Most likely he was involved in clearing forest land for building the Panagarh Airport.

A: And your mother?

K: (Her name was Annapurna Devi) She was a housewife. She didn’t have much formal education. But she was all along very attached to literature. From the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Kashi Khanda to Bengali authors such as Sarat Chandra (Chattopadhyay), Bankim Chandra (Chattopadhyay), Rabindranath – she read everything. Therefore books of various authors such as Tarashankar (Bandhopadhyay) and Bibhutibhushan (Bandhopadhyay) were lying around the house when we were growing up. We had a subscription to the DoinikJugantar.

A: As a child, was it from listening to stories from your parents that you developed an interest in literature?

K: It’s not like we heard a lot of stories [growing up]. … I later learnt that father had published two books of verse. One was called Charon (Eulogies), the other Leelamoyi (The Colourful one). We recovered a section of Charon which I have seen, but Leelamoyi was lost with the house. Apart from this we had found a notebook with poems. And at one point Sailajananda (Mukherjee) had asked him to write a story for a film – that story was also there (recovered), but I can’t say if he had ever handed it over. … Father had written songs for some movies too. … I don’t think he was writing, or had the time to write, in the last two or three years of his life – working as a military contractor claimed a lot of his time.

A: So it was your mother who brought you all up in Varanasi? … Then she must have had to work?

K: No, actually we were quiet affluent. Because we had a very big family, they had built a house with 21 bedrooms. (laughs) It was a huge affair.

A: For how many people?

K: As in for the whole family. But no one came. So it was the four of us … (Laughs) … We didn’t have much by way of financial troubles. … Part of the house was given for rent.

A: So while you stayed in Varanasi your father had to come this side [to Bengal] very often? Whether that be for work or …

K: No, father couldn’t spend much time with us.

A: Only you all had been sent there for your health?

K: Yes we had been sent there … Father couldn’t stay there much.

A: Did your family have any kind of political affiliations?

K: No.

A: Freedom struggle? Swadeshi?

K: Yes at home there was, father would bring over people involved in the swadeshi movement. … He was drawn towards people in the Swadeshi movement who were pro-people (of a sort). Not in Varanasi, but here. Only here. Actually father had wanted to stay in Kolkata, as he was himself a writer … His poems were published in all major papers/magazines of the time …. From Kallol to everywhere.

A: Where is your mother from?

K: My mother is from a place they call Sonamukhi, in Bankura district.

A: So did she face any difficulties in moving to a new place like Varanasi?

K: No I don’t think she had a lot of difficulty. Or even if she did, she never let anyone get any sense of it. She was an extraordinary woman in a way. Through so many crises … in an affluent house like ours boys have a high chance of going wayward, but that happened to none of us. At the same time she never hit us while growing up.

A: So what do your two brothers do?

K: … One brother was a police offer. … When he felt conflicted about it … then he was sent, with whatever remained of our money, to start a business in Varanasi. … He started a shop for sarees, but that didn’t work out, so later he started work as a marriage registrar. He worked well there, … and now he is retired. Another brother is in the USA. … He did an MA from Banaras Hindu University on Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, and an MA in English from Kashi Vidyapeeth. … and over there he first taught English, at a regular small college … then he did business administration. Then he entered the hotel business as an entrepreneur[x].

A: That is, he owns a few hotels?

K: No no, not hotels, not a few. He had a few restaurants. … But he is a very honest person – you see, more or less honesty is something that is there in our [immediate] family – and honesty and business doesn’t go very well. (laughs) … I tell him you are part of the American working class … but you are thinking of [yourself as] the American bourgeoisie. … At one point he had seven restaurants. But his managers used to live much better [than him] …

A: And now …?

K: … he had built everything with loans, it’s all gone. Now he works in a restaurant … near Washington … Practically he doesn’t have anything … but he has built relationships … he has written an English novel too, titled Room Service Mafia. But he hasn’t finished a final draft. I think it has a tremendous possibility. … When he first went to the US, I would press him, and one by one he sent three pieces, about his experiences in the US, in Hindi. And they were highly acclaimed on publication, writers liked them. A friend of mine, Dr. Vijay Mohan Singh, he was a prominent Hindi critic and editor, he had asked that my brother keep writing. But maybe after a few days he lost interest in continuing. …

“Amukh,” Issue 5 (around 1966, or early 1967), cover page. Art: Bibhas Das.

Early writing and politics

A: When did you first write?

K: I started writing close to the 60s …

A: … As in when you were approximately 24 years old?

K: … I wrote in the late 50s too … also worked as an editor . I was the editor of a Bangla magazine called Ahoban (Call), for almost two years, from about ’57.

A: … Before that, when did you start writing by yourself, whether they were published or not?

K: No my works were published. … In some magazines in Bardhaman[and so on] … Even before I became a writer as such, I had published ten books … I had given to publishers, and they published … this would be in the early 60s. It was after Amukh, and especially once I started developing a political understanding, then I started thinking of what my writing is for. From when I started Amukh I was thinking about writing. … Before that I had experimented in all forms. I wrote short stories, novels, travel writing, essays, plays, …

A: So you started all this while in school?

K: Towards the end of school … I would write in Bangla. I had a Sanskrit teacher, he challenged me, saying Bengalis cannot write in Hindi. As a result … (smiles)

A: So towards the end of your schooling you started writing in Hindi?

K: Yes. … Over there in Varanasi there’s this daily called Aaj (Today), I would write in that. Among the new authors Aajcounted at that time as having introduced to the readership, I was considered one. Another one was a friend of mine, Sayyid Safiuddin. He used to write exceptional stories for a long time. He was the son of a jailer. … But he stopped writing. … I was a bit of a rebel from the beginning. From rebel to revolutionary was a logical conclusion, and I came towards the revolution.

A: Why do you say you were a rebel from the beginning?

K: Because of the events that happened in my life. For example after my father’s death, living in an alien land, the kind of behaviour that I have seen from people … relatives … to grab whatever money we had left. One of my paternal aunt-in-laws (mejokakima) told my mother, I’ll make you go around this Varanasi begging with a bowl in your hand. … I think our father was an intelligent man, but somehow he fell into religious stuff. He was attached to a matha (Hindu monastery) there, and they would exploit him in different ways. … Father would not send money to our house. He would send money to the ashrama, and they would take care of us. … They were responsible for everything in our house, from getting ration to whatever in that vein. And they exploited the situation to the hilt. … How all these relatives made so much money … Therefore I [saw] this whole exploitation very closely … [and was born] a rebelliousness against religion, against these people, relatives. I didn’t have a childhood. I became head of the family at the age of 8.

A: By rebellion you mean you would create a ruckus at home?

K: No no … I would ignore them in all matters … I wouldn’t go to the ashrama … I didn’t abide by many of their strictures – you have to do this, no I won’t! I was never someone who created much of a ruckus. I had a very silent personality, but the decision is mine, and in that way …

A: … In that sense from when did you start thinking politically?

K: Politics – see – I had a notion that Communists are good people.

A: Why did you have such a notion?

K: Given what I have seen, I have seen some men. They were in CPI, in Varanasi … There we knew one person called Rustom Satin [later elected MLA for South Varanasi in 1967]. … Later I saw that there were many problems with him too. But even so I would think that they are honest … and the communists stood apart from all these Congress types, or others who were political socialists of other kinds, or people of different political parties. … But no one ever tried to persuade me to become a communist … I used to pay donations etc. The first Lok Sabha elections after I turned 18, I was an election agent in it, for CPI. I had never voted myself, having seen all the theft and robbery perpetrated by the Congress, and I came to see that there was no point to doing this.

A: After that, after CPI, you started thinking differently?

K: I actually became politically conscious after Naxalbari. From ’65 we started Amukh. Before that I ran a monthly magazine called Maral, means “duck” in Hindi. They started it as a commercial magazine but failed. There was a press called Eureka Press, they launched it with much fanfare. But they couldn’t choose an appropriate editor. Ramchandra Verma was an established writer of dictionaries, but he couldn’t run a literary magazine like that. So then one of the younger brothers in the family that owned the publication, came to me and asked to take on the editorship of Maral. So I told him I could run it as a little magazine, but not as a commercial magazine. Then he said ok, you do it. … I said I have one condition, that you won’t interfere in the magazine’s matters. So he said no, there will be no interference in matters of editorial decision making over literary matters. Amar Dutta said this to me … Paresh Dutta was the publisher. Amar Dutta was his younger brother. … During my editorship Maral was a very dynamic publication … It created a storm. Because those who were the established writers then, such as Mohan Rakesh[xi], Rajendra Yadav[xii], Kamleshwar[xiii], I started by criticising their manipulation (laughs) …

A: As in politically, their …

K: Yes, about their writing. Launched attacks on their control over the domain of writing. And they had developed like a gang. In Hindi literature this kind of gang-ism was always there. One Hindi poet, Shrikanta Verma, said to me, “We await your magazine to see which writer you will go after this time.” … A promising writer then was Ravindra Kalia[xiv], he was an upcoming new writer. He used to write a regular column, as “Karbi,” called Maurice Nagar se Maurice Nagar tak (From Maurice Nagar to Maurice Nagar). There was a bus route from Maurice Nagar to Maurice Nagar, would go around all of Delhi, he would write about that. It became very popular. … I used to attend to two priorities. On the one hand I attacked the godfathers who practiced a pseudo modernism … On the other hand, parallel to it, those who were writing good new literature [I created space for them], such as Vishnuchandra Sharma[xv] … his memoirs … then Madhukar Singh[xvi] … later he became an established short story writer … then as poets Dhumil[xvii], Vijay Mohan Singh[xviii], and many others. Rajkamal Chaudhari[xix], was already an established writer, he would write regularly in our magazine. … In January 1965 we brought out the last issue. And that issue was a collection of new writing in Bangla – “Bangla Navlekhan Ank” (Bangla New Writing edition) … In that Phanishwar Nath “Renu”[xx] wrote a long essay called Ram Pathak ki diary (Ram Pathak’s diary). In that he discussed the literature from Krittibash to the Hungry Generation[xxi]. Sharad Deora wrote a novel about the Hungrys, titled College Street ka messiah (Messiahs of College Street) … I supported the Hungry Generation for one reason, the police arrested them at that time for obscene poetry, and that … we would not tolerate any police interference in literary matters … Rajkamal was the co-editor of that issue, with me. And this was Maral’s last issue.

Issue 6 of “Amukh” (probably around 1969), front cover. Art: Karunanidhan Mukherjee.

Amukh

A: Why did it [Maral] stop?

K: … Actually there were many who did not like this … So there was this proof-reader, and one person who worked for the radio, and they said we could run this too. … One person went and showed some words used to the owner, claiming they were obscene … And that apart there was an economic reason too. The person who used to arrange for the advertisements from Bombay, he got a good job elsewhere, and didn’t need to do the job that got us advertisements any more. As a result that magazine financially … I felt that, at that time what was most needed was a magazine, because we had already lit up the Hindi sphere in a big way … Then in Connaught Place, in Delhi, there was a restaurant called Tea-House, and they had a book store. And that was the biggest adda of people associated with literature. I have never seen a great place like that … there our magazine sold the most … for almost two years … Before that, at first, I used to run a Bangla magazine called Ahoban (Call), for almost two years. Then I did a magazine called Nagfanni (Prickly Pear) … there were three issues of that one … Police (later) took away all of these. Nagfanniwas a satirical paper … Even that didn’t work out. Then came Maral … and when that ended we felt, we have to do something ourselves. Then we thought of Amukh. Among the Amukh group, I was the only writer. The other four were artists. Amongst them Anil Karanjai (later) also got Akademi awards etc. He was a very diligent and great artist … Amongst them another person was Bibhas Das. He used to work in the Air Force, left it and came … Another person was Karunanidhan, and then Subir. … Bibhas Das had great potential, but he could not cultivate that as an artist. Which Anil could do. … All of them had to fight for a commercial existence, even Bibhas had to do that. Yet Bibhas had a new kind of vision, exceptional! You can see some shadows of that in Amukh. … Anil Karanjai lived on as an artist, he has now passed away. At one point it happened such that we were all in Delhi, except Subir. Subir (Chatterjee, but would write only “Subir”) later started a homeopathy wholesale shop. … In Delhi the financial concern is a big one, you need a lot of money for your existence … In Kolkata its possible to some extent … you can struggle and get by … as a result the commercial needs wrung him out dry. Anil had an advantage – both his first and second wife – they were earning the money. …

A: As a result he was able to experiment more with his art?

K: Yes he was able to. And he had this other thing, he wouldn’t make any compromises … Otherwise after getting an Akademi award, those who make compromises, they never have to turn backwards. But he didn’t do that. … All of them in some way or the other remained supporters of the revolution.

A: Even though not directly?

K: No. Though at one time, when they were in Varanasi, they did plays … posters … At the point when the party wasn’t pursuing any open activities, and when RWA (Revolutionary Writers Association) writers were arrested, we arranged the biggest protest in Varanasi. We took out a huge rally with big images of people such as Subbarao Panigrahi, Saroj Dutta[xxii] – Saroj Dutta had already been murdered by then. We took out the rally and [after a short while] disbanded in a flash … After the rally reached a certain point we held a meeting, and then went out through small lanes … before the police could do anything. It takes the police some time to get the news and act on it. As a result in Varanasi the police knew only my name. They didn’t know of any of the others who were involved. So we did all this. … In the Russian revolution, the way Mayakovsky and others did workshops … we didn’t do that kind of work anywhere. But it’s happening now, in Dandakaranya. It’s there in this book [Three Decades of Dandakaranya Literary and Cultural Movement 1980-2010, published in Telugu in 2010; English translation by N Ravi, and Bangla translation by Kanchan Kumar, forthcoming then, and published in 2017], how they are organising workshops, and how they are benefited by them. While working on Amukh we did not conduct workshops about writing, but we should have I think … But we discussed each other’s writing, it was a collective endeavour.

A: What would you describe as your first organisational experience?

K: … Amukh itself can be described as a kind of organisation. Even Maral … art and literature of course does not develop by itself in a different way, it is a like a bunch of grapes, many things together … We had one advantage that during our time [the famous American poet] Allen Ginsburg came to Varanasi. For over one year he and Peter Orlovski were there. We had the privilege of reading many avant-garde magazines … he used to give them to us. There was one exceptional magazine called Evergreen Review – later it started publishing pictures of naked women – but in the earlier phases they published a lot of the new writing that was starting to come out worldwide. … It was there that I first read an interview with Fernando Arrabal[xxiii], and a play by him. Like that, we proceeded with Amukh, trying to develop it as an avant-garde magazine. … For instance you will see in the early issues of Amukh, we did not quote any major authors. Those of us who were writing for it, would quote each other. In the first issue we published an interview of the young artists amongst us – Anil and Karuna gave a joint interview about their lives, and stated some of our views. …

A: How did you get interested in theatre?

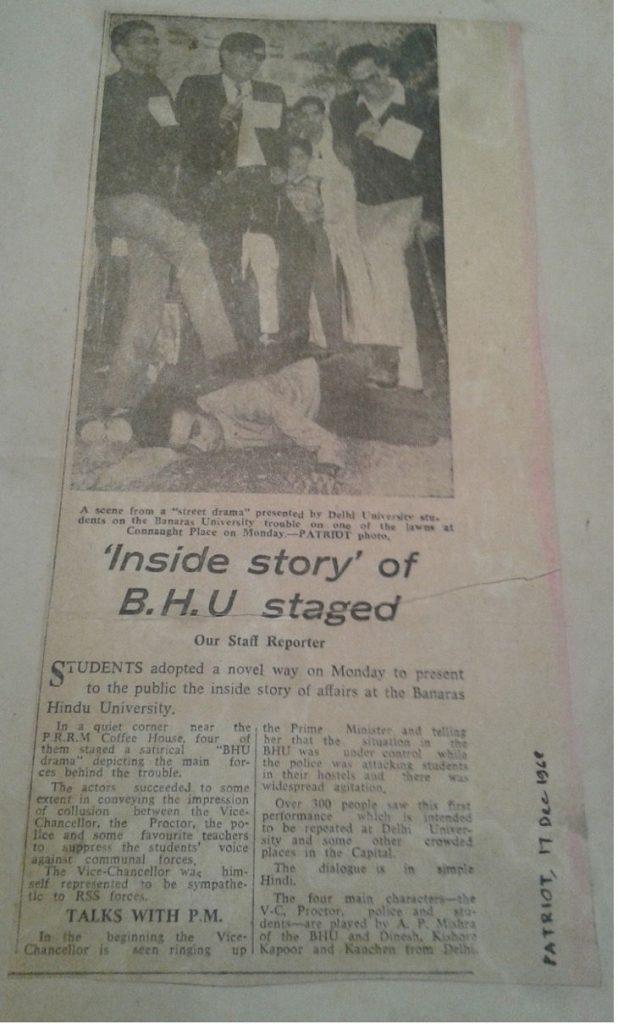

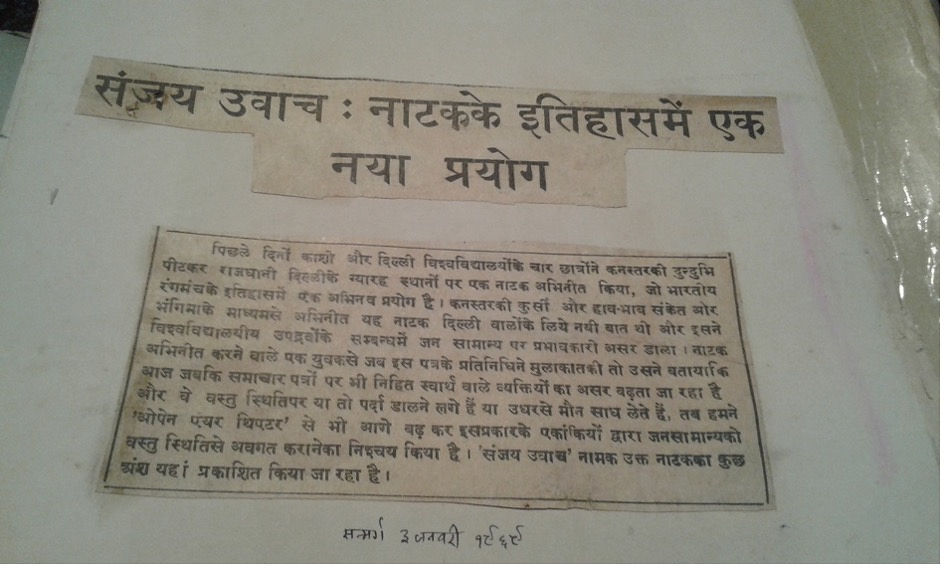

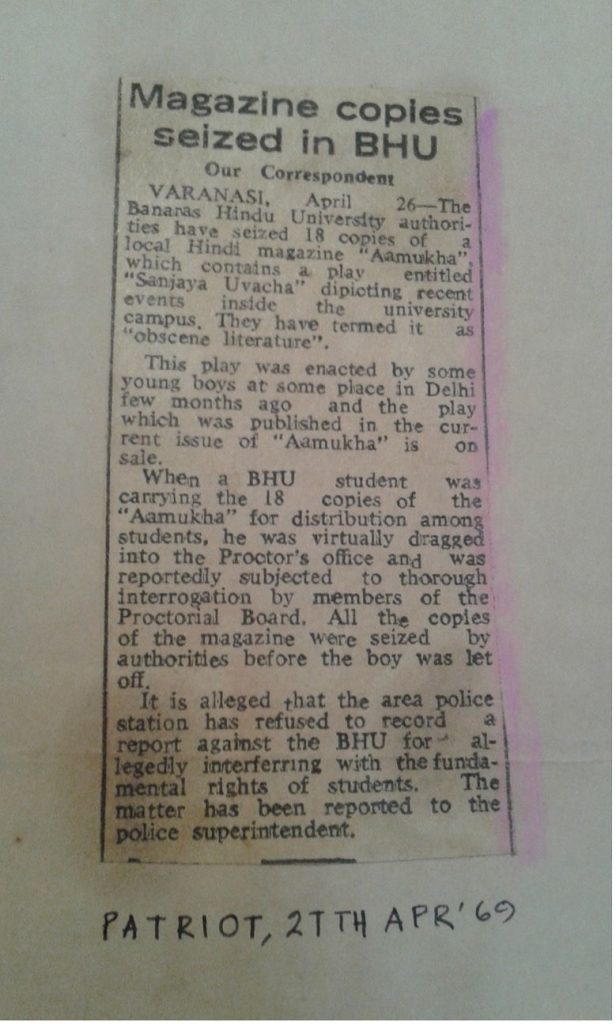

K: I used to act in plays there. I used to act in a Bangla theatre group called “LolitChokro”. … I had just left school at that point. … Then I thought they were of an older sort. In general they were doing good Bangla plays. … But most of them were old … they would frame things to the convenience of their characters … young people had no space. Then I thought … we have to think about this. I couldn’t immediately find a Bangla theatre group. Then this new (Hindi) group had started, called “Natya Parishad” – some postal workers used to run it. I joined that as a translator. I translated a play by Narayan Gangopadhyay called Agontuk (One who has come). It was a very good play, modern too, in the contexts of the time. And another play by Shibram Chakraborty called Jokhon Tara Katha Bolbe (When they will speak). It was an exceptional play. … That man was very talented … He has a book called Moscow theke Pondicherry (From Moscow to Pondicherry), with debates around Marxism. Like that I did some (translation) work. We also produced a play called Ladai ke maidan mein picnic (Picnic on the Battlefield, by Fernando Arrabal). We staged it at their Nagri Natak Manch, which was the biggest stage there, and won the first prize. There were plays from all the big groups in Varanasi. But their thing was they were very traditional … So against us, there was this evening daily called Banaras, it’s editor was Rajkumar, he used to think I was a communist (laughs) … and thinking I was a communist he would target me. So there was a scene with alcohol consumption on stage. But a picnic in a western context, its not unusual to have alcohol! [But to that they were like] – Drinking alcohol on stage! On the holy stage! So like that. Then there was a big debate about this. In this debate Dr. Bhanushankar Mehta[xxiv]wrote an essay pseudonymously in our support. … At that time there was also a student movement in Banaras Hindu University. There was a man called A. C. Joshi, from an RSS background, who became Vice Chancellor. And at that point the Naxalite movement hadn’t yet issued the call for election boycotts. Then we formed a United Front, and supported a student organiser from CPI, N. P. Singh, for the Secretary position in the student union elections. And he won the election. One of the main factors behind his victory was an engineering student, A. P. Mishra, who was from an RSS background, but moved to the left. … Then RSS people beat up A. P. Mishra and N. P. Singh with iron rods. … A movement grew out of that. The university (adjourned) sine die. Earlier BHU had 10,000 students, and [after the protests] they cut it down to 5,000. The situation became such that one couldn’t say anything about the university in Varanasi. There was Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) all over the city, they tried to send students home. At that point our house was a shelter for the students. … At that point an engineering student, Satrajit Majumdar (now an astrologist), wrote a play called Sanjay Ubacho[Thus Spoke Sanjay; Sanjay – a character from the Mahabharata, figured as a war-reporter for the unseeing, speaking about the developments in BHU]. The night before we had performed Ladai ke maidan mein at the Nagri Natak Mandali, and then I translated Sanjay Ubacho into Hindi [from Bangla] overnight. We decided we will go to Delhi and stage the play.

One of many newspaper reports in English and Hindi about the play’s performances, that Kanchan Kumar had collected. Kanchan Kumar is to the right, holding a cane, placing one foot on the prone body of a student.

A report on the play in the “Sanmarg,” which registers the surprise of the form of street theatre. This was a decade before Safdar Hashmi and Janam would do their first street play in Delhi. Compared cross regionally, this was also before Badal Sarkar would start performing outside proscenium stages.

One of several reports I photographed from Kanchan Kumar’s collection in 2015, about copies of “Amukh” being seized on BHU campus. This issue had included the publication of “Sanjay Uvach,” making it a target.

Cover Photo: Kanchan Kumar photographed by me on January 16, 2024, outside the apartment in Jadavpur that he rented, and where he was based for most of the last two decades. He moved to a home for the elderly later that year.

Author Bio: Abhishek Bhattacharyya is an academic based in New York. His research is on cultural and political trajectories of the left in South Asia in the late twentieth century.

End Notes:

[i] Gummadi Vittal Rao, better known as Gaddar, was a revolutionary Telugu balladeer, who passed away in 2023. Gaddar started getting involved with revolutionary politics and culture-work from the 1970s (in 1979 he had already performed in a movie, Gautam Ghose’s Maa Bhumi), and it was in the 1990s that he emerged as a towering figure. He was a core member of the cultural troupe “Jana Natya Mandali,” and his book Tharagani Gani(Endless Mine of Songs) was published in Hindi translation in Amukh starting in 1994.

[ii] His songs also figure in Anand Patwardhan’s Bombay and Jai Bhim Comrade. In January 1998 Amukh published a special issue in his memory.

Throughout this essay different prominent cultural workers are referenced, who people unaware of the literary histories of the languages/regions concerned may be unaware of, but people engaged with those contexts would find very familiar. I have tried to briefly contextualise such figures in footnotes, without providing extensive references for each.

[iii] Laal Singh Dil (1943 – 2007) is one of the most prominent dalit revolutionary poets of Punjab – Nirupama Dutt’s English translation of his work was published some time back by Penguin. Kanchan Kumar’s Bangla translation of this book was serialized by the little magazine Ikkhon, and will be published posthumously as a book.

[iv] For a review of the book by Shoma Sen: https://thepolisproject.com/read/viyyukka-women-revolutionaries/

[v] For Bangla readers curious to read poems by his father and learn more about him: https://www.milansagar.com/kobi/kanakbhushan_mukhopadhyay/kobi-kanakmukh.html

[vi] In 1930 Tagore wrote an English poem called “The Child,” later translated into Bangla as “Sishutirtha”, which features a similar line (later made famous by Ritwick Ghatak’s film Subarnarekha, 1965): “Joy hok oi manusher oi nobojatoker oi chirojibiter.”

[vii] Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899 – 1976) was a famous poet and song-writer (Nazrul Geeti), also nicknamed “bidrohikobi” (rebel poet). In the Indian Office collection of literature proscribed by the British raj, he is the most frequently recorded individual poet. He was later feted as the national poet of Bangladesh.

[viii] “Sailajananda Mukherjee (1901-76): Bengali director born in Andal, Burdwan District. Noted Bengali novelist and contemporary of Kallol Group. Closely associated in early youth with writer-musician Kazi Nazrul Islam. Worked in Raniganj collieries, the location of his first major literary work, Koila Kuthi, … Directed works are early instances of a commercially successful cinema set among peasantry and urban working class” – from https://indiancine.ma/AKQA/info

[ix] “Kamal Mitra (1911-93): Bengali actor born in Burdwan. Started in amateur theatre. Film début with Gunamoy Bannerjee and in Debaki Bose’s Hindi films. First major hit: Sat Number Bari, coinciding with his successes on the professional Calcutta stage (Seetaram, Tipu Sultan, etc). Acted with Minerva, Star and Srirangam theatres and in jatra groups.” (from https://wiki.indiancine.ma/wiki/Kamal%20Mitra , accessed in 2015 – link does not work currently) He acted in numerous films, including Sabyasachi (1948), Thana ThekeAschi (1965) and Sabar Uparey(1955).

[x] When I texted his US based brother, Jugal Mukherjee, in January 2026, he offered some minor amendments to this account. He said he completed the Kashi Vidya Pith masters, but was in the BHU MA program (in the Indology department, on Ancient Indian History and Culture) for only one year, because he got a job offer in the US. He used to work as a tour guide in Varanasi for the Govt of India, before he was recruited by a tour company for a branch manager job in their New York office. Once in the US, he did a diploma in business administration. He worked in the hotel and restaurant business, and then at one point owned 8 restaurants, one night club and a gift shop. I should also note that his book, Room Service Mafias, was published in 2023.

[xi] Mohan Rakesh (1925 – 1972) was a prominent Hindi writer and playwright. His famous plays include AdheAdhure (1959) and Ashadh Ka Ek Din (1958). He won an Akademi award in 1968.

[xii] “Along with Mohan Rakesh and Kamleshwar, [Rajendra Yadav] was one of the pillars of the naikahani movement which ushered change in both the content and style of Hindi short stories. Yadav’s style was simple and direct; his stories often sought to capture the shifting sands of social and moral values in post-independent India. ‘Jahan Lakshmi qaid hai’ is one his most remembered short stories.” “And he penned the much-acclaimed novel Sara Akash, which later became a celebrated film.” From http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Eminent-Hindi-writer-Rajendra-Yadav-passes-away/articleshow/24887036.cms

[xiii] Kamleshwar (1932 – 2007) was a prominent Hindi writer and screenwriter. He won the Akademi Award in 2003 for Kitne Pakistan, and the Padma Bhushan in 2005. Some recordings are available here: https://www.loc.gov/acq/ovop/delhi/salrp/kamleshwar.html

[xiv] Ravindra Kaliya (1938 – 2016) was a noted writer and journalist, whose works include the collection of stories, Nau Saal Chotti Patni. He was also the director of Bharatiya Jnanpith.

[xv] A couple of his poems are available in English translation: http://lifeandlegends.com/vishnuchandra-sharma-%E0%A4%B5%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A3%E0%A5%81%E0%A4%9A%E0%A4%A8%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B0-%E0%A4%B6%E0%A4%B0%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AE%E0%A4%BE-translated-by-kalpna-s/

[xvi] While I could not find an English article about his work, here is a short piece in Hindi for the curious: https://www.forwardpress.in/2021/02/remembering-madhukar-singh-hindi/He is here mentioned amongst a series of Hindi writers who were born in the 1930s, same as Kanchan Kumar.

[xvii] “Sudama Pandey “Dhoomil” (1936 – 1975), most commonly called Dhoomil, was a renowned Hindi poet from Varanasi, who is known for his revolutionary writings and his “protest-poetry”, along with Muktibodh./ Known as the angry young man of Hindi poetry due to his rebellious writings, during his lifetime, he published just one collection of poems, Sansad se Sarak Tak, (From the Parliament to the Street), but another collection of his work, entitled Kal Sunna Mujhe was released posthumously, which in 1979, went on to win the Sahitya Akademi Award in Hindi.” From http://indicollect.com/sudama-panday-dhoomil/ (link accessed in 2015, currently no longer available)

[xviii] “Vijay Mohan Singh (1936 – 2015) began as a short story writer and soon came into prominence as part of the post-1960 crop of writers that tried to break free from the so-called Nai Kahani (New Story) promoted by the trinity of Mohan Rakesh, Kamaleshwar and Rajendra Yadav. Singh not only wrote short stories but also defined the new aesthetics of what he chose to term as “Sathottari Kahani” (“Post-1960 Story”). Gyanranjan, Doodhnath Singh, Kashinath Singh and Ravindra Kaliya were some of the notable short story writers who emerged on the literary scene after the Nai Kahani began to lose its steam. A common trait among all these writers was their search for a new style, idiom and language to express a new kind of experience. This was the experience of a generation that was facing the disillusionment of the post-Nehruvian era. Politically, this disillusionment found its expression in the comprehensive defeat of the Congress in North India in the 1967 elections.” From http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/society/fiction-writer-vijay-mohan-singh-dies/article7260947.ece

[xix] Rajkamal Chaudhari (1929 – 1967) was a Hindi and Maithili writer. Biswajit Sen writes: “He died early, at the age of thirty seven years and six months. During this short lifespan, he left, for the Hindi and Mathili readership, a great wealth of material—six short-story collections, six poetry collections and twelve novels. Alongwith this, he translated into Hindi the epoch-making Bengali novel Chowringhee by Shankar, the eminent Bengali novelist of considerable repute. He also edited the “complete short stories” of Pandit Bechan Sharma ‘Ugra’. / … In his political belief, he was a Marxist. Rajkamal applied for membership of the CPI when he was quite close to death.” https://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article3519.html

[xx] “Phanishwar Nath ‘Renu’ (1921 – 1977) was one of the most successful and influential writers of modern Hindi literature. … popularly known as Renu, is one of the great Hindi writers of the post-Premchand era. He is also a freedom fighter, memoirist, an active political and social activist, poet and lyrics. He is best known for promoting the voice of the contemporary rural India through the genre of ‘AanchalikUpanyas’ (Regional Story), and is placed amongst the pioneering Hindi writers who brought regional voices into the mainstream Hindi literature.” From http://www.pnrsssansthan.org/biography.htm (link accessed in 2015, not currently available)

[xxi] “The Hungry Generation poets and authors tried to explore how far their contemporary society would allow them to subvert the limits of established culture. / At the height of the movement in 1963, they delivered masks of animals, demons, clowns and cartoon characters to the homes famous and influential people. On the masks were printed: “Please take off your mask — the Hungry Generation”. / All hell broke loose! On September 2, 1964, Malay, Samir, Debi Roy, and associates Subhash Ghosh and Saileshwar Ghosh were arrested on charges of obscenity and criminal conspiracy. Malay was convicted and fined for his poem Stark Electric Jesus. It was only on July 26, 1967, that the Calcutta High Court exonerated him. / But he is still rebelling. Asked the reason for refusing the Sahitya Akademi Award, Malay said: “I do not accept any literary awards or prizes as they reflect the value judgments of the dispensation which bestows them.”” From https://www.telegraphindia.com/bihar/hungry-poets-ginsberg/cid/368996 There are various blogs dedicated to them that I could find online, including these two: http://hungryalistgeneration.blogspot.in/ and https://hungryalist.wordpress.com/

[xxii] Saroj Dutta (1914 – 1971) was the arch poet of the Naxalite movement in Bengal, and became the editor of Deshabrati, the Bangla organ of the West Bengal committee of CPI-ML. The 2018 film S.D.: Saroj Dutta and His Times, directed by Mitali Biswas and Kasturi Basu, can serve as a helpful introduction for Anglophone audiences as well.

[xxiii] Fernando Arrabal, born 1932, is a Spanish playwright, screenwriter, director, novelist and poet. For more: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fernando-Arrabal

[xxiv] Dr. Bhanushanker Mehta (1921 – 2015) was a prominent actor, director and writer based in Varanasi. He was the President of the Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi for six years. https://rajkamalprakashan.com/author/bhanushankar-mehta?srsltid=AfmBOorD_b5Cl4YP3qPc5776J10DScJg7A199bmrtiuHBeOLEXbcVtgM