After two freezing nights of open-air dharna outside the Alipurduar collectorate, women tea workers from seven Merico-run gardens in the Dooars forced the company to issue a written assurance on clearing long-pending wages. The struggle, led overwhelmingly by women, exposed the exploitation of tea gardens workers, administrative apathy towards their plight, and the political party affiliated union–management collusion.

Groundxero | January 7, 2026

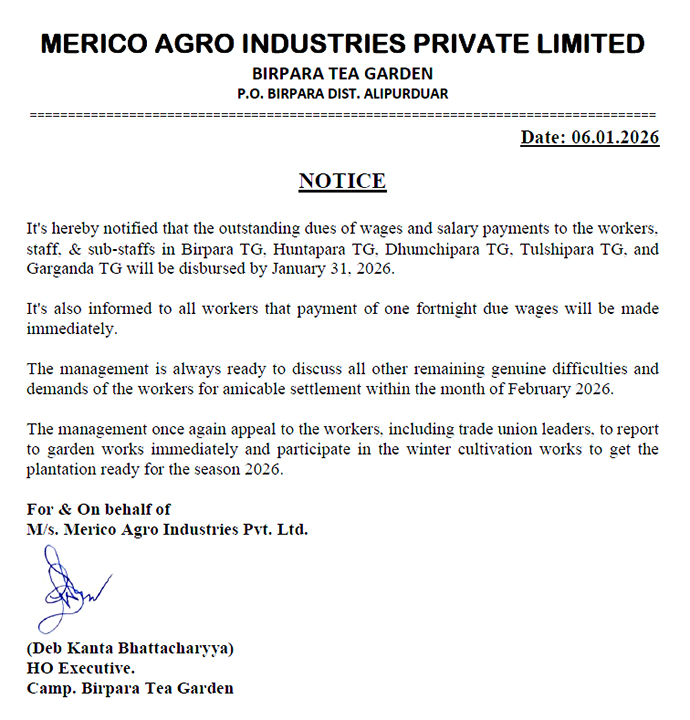

After two freezing nights of protest under open-sky outside Dooars Kanya, the district collectorate of Alipurduar, tea garden workers, most of them women, from seven Merico-run estates finally forced a partial breakthrough late on Tuesday night. At around 11 pm on January 6, nearly 200 women workers sitting on dharna received a written assurance from their employer, Merico Agro India Industries Limited, committing to clear all outstanding wages and salaries by January 31, 2026, with one fortnight’s payment to be made immediately.

The assurance came after sustained struggle of the workers, organised under the banner of the Chai Shramik Ekta Andolan, and following a late-night intervention by Trinamool Congress Rajya Sabha MP Prakash Chik Baraik, who arrived at the protest site along with Gopal Biswas, Joint Labour Commissioner (JLC), Alipurduar.

A written notice from the company was shown to the workers sitting at dharna, and the administration also assured a second meeting in February to discuss the workers’ remaining demands, including provident fund, gratuity, bonus etc.

After discussion among themselves, the workers agreed to lift the dharna by 12 noon the next day (on Wednesday)—but only after receiving an officially signed and sealed copy of the notice from the Joint Labour Commissioner, underlining the deep mistrust on management bred by months of broken promises.

Unpaid Wages, Broken Promises

The core issue that triggered the agitation is unpaid wages—ranging from three to seven fortnights—across seven Merico-run tea gardens in the Dooars. With no income for months, workers were pushed to hunger, debt, and despair. The current phase of the struggle began on December 29, when around 300 workers, a majority of them women, held a peaceful “Dooars Kanya Chalo” march and sat on a dharna through the night, demanding that Merico issue a written, time-bound commitment to clear at least the outstanding wages.

Workers pointed out that denial of wages is not only illegal under labour laws but a constitutional violation, striking at their right to life and dignity. Yet, when workers delegations sought to meet the District Magistrate and the ADM (LR), Alipurduar, both officials refused, citing preoccupation with an Election Commission of India visit. The Deputy Labour Commissioner (DLC) met the workers but expressed helplessness and offered no concrete assurance. This reflected the administration’s unwillingness to act against a powerful employer.

Even as the women workers sitting on dharna shivered outside Dooars Kanya, the administration was busy, preparing for the Dooars Utsav, a festival meant to showcase the “culture and beauty” of the region, ignoring the injustice faced by hundreds of tea workers.

The December 29 dharna was temporarily lifted around 11 pm after intervention by Labour Minister Moloy Ghatak, who announced that a tripartite meeting between workers, management, and the labour department would be held to the resolve the issues. The minister assured that Merico would be compelled to present a schedule for clearing all wage arrears by February 2026. He also assured workers of initiating legal action under the Payment of Wages Act, including possible cancellation of garden ownership, if the company failed to comply.

The Failed Triparite Meeting

The immediate trigger for the renewed dharna from Monday was the collapse of a promised tripartite meeting between workers, management, and the labour department.

Despite repeated scheduling, the meeting was postponed three times (December 31 → January 2 → January 5) as the management failed to appear. On January 6, barely an hour before a scheduled 1:30 pm meeting, Merico sent a letter refusing to negotiate with the protesting workers’ representatives and stating it would speak only to TMC- and BJP-affiliated unions, while asking for yet another 15 days to “arrange funds” for wages long overdue.

Significantly, those very unions had earlier written claiming they were too busy to attend the tripartite meeting, exposing a clear nexus between the management and ruling-party-affiliated unions. Representatives of the CBMU (CITU), though formally invited, were barred from the meeting.

During the aborted talks, the Deputy Labour Commissioner admitted that non-payment of wages constitutes a criminal offence, yet refused to initiate action, shifting responsibility to the District Magistrate—who, in turn, declined to meet the workers.

The consequences of this apathy were immediate and devastating. As news of the failed talks spread, Mahakal Oraon, a worker from the Tulsipara Tea Estate who had come for negotiations, allegedly attempted suicide by jumping from the fifth floor of Dooars Kanya. He survived but the incident starkly exposed the psychological toll of prolonged wage denial.

Later that night, as temperatures dropped to around 12°C, Migni Oraon, a woman worker from Hantapara Tea Garden sitting on dharna under the open sky, fell seriously ill and had to be rushed to hospital.

“The worker had come for negotiations. When the talks failed, he tried to take his own life. This is unfortunate. The administration should act against the management for its negligence,” said a workers’ organiser.

Solidarity Across Political Lines

Throughout the protest, CITU provided sustained logistical and organisational support, alongside activists such as Abhijit Rai of AIUTUC. Solidarity also came from a Congress councillor and the Youth Congress district president, as well as activists from other Left unions. Workers from Raimatang, Chinchula, Madhu, Majherdabri, and Madhu Tea Gardens joined the protest in solidarity.

This rare convergence across political affiliations demonstrated the strength of worker unity beyond party lines. As workers pointed out, it was precisely this collective pressure—from below and across organisations—that forced the administration and management to respond.

Women at the Forefront of the Struggle

The struggle has been led overwhelmingly by women workers, who sat through their dharna despite freezing temperature for two days and nights, and their participation in all decisions showed that women workers can lead union struggles. It is their determination that forced the administration to finally respond.

Yet women who spoke up also faced targeted retaliation.

On the morning of January 6, Apsara, a permanent worker at Birpara Tea Garden, was removed from work without any written order or notice—solely for participating in the protest. When she questioned this illegal action, the garden manager allegedly sexually harassed, assaulted, and humiliated her, even abusing her deceased son. With no POSH committee or Internal Complaints Committee in the garden, Apsara was left with no option but to approach the police and seek registration of an FIR under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS).

Her case underscores the everyday violence and intimidation faced by women tea workers who dare to organize and resists exploitation.

A Partial Victory

The late-night assurance marks a hard-won but partial victory. Wage payments have been promised before—and broken. That is why workers insisted on written commitments with official seals before agreeing to suspend their protest.

What remains undeniable is that the struggle has already rewritten the script. Through two days and nights of open-air dharna in freezing temperatures, women workers led discussions, made collective decisions, and forced accountability where administration had failed.

The sit-in has been lifted temporarily, but the fight is far from over. Workers’ slogans echoing outside the Alipurduar Collectorate today afternoon reiterated their resolve: wages delayed are wages denied; workers’ dignity cannot be postponed, and the struggle will continue till all demands are met.