How durable is the foundation of faith of an institution that was willing to abandon its creed on such flimsy grounds as a dispute with its employees and how strong morally are those who defend it today with ostentatious valour?

Nilanjan Dutta

May 22, 2024

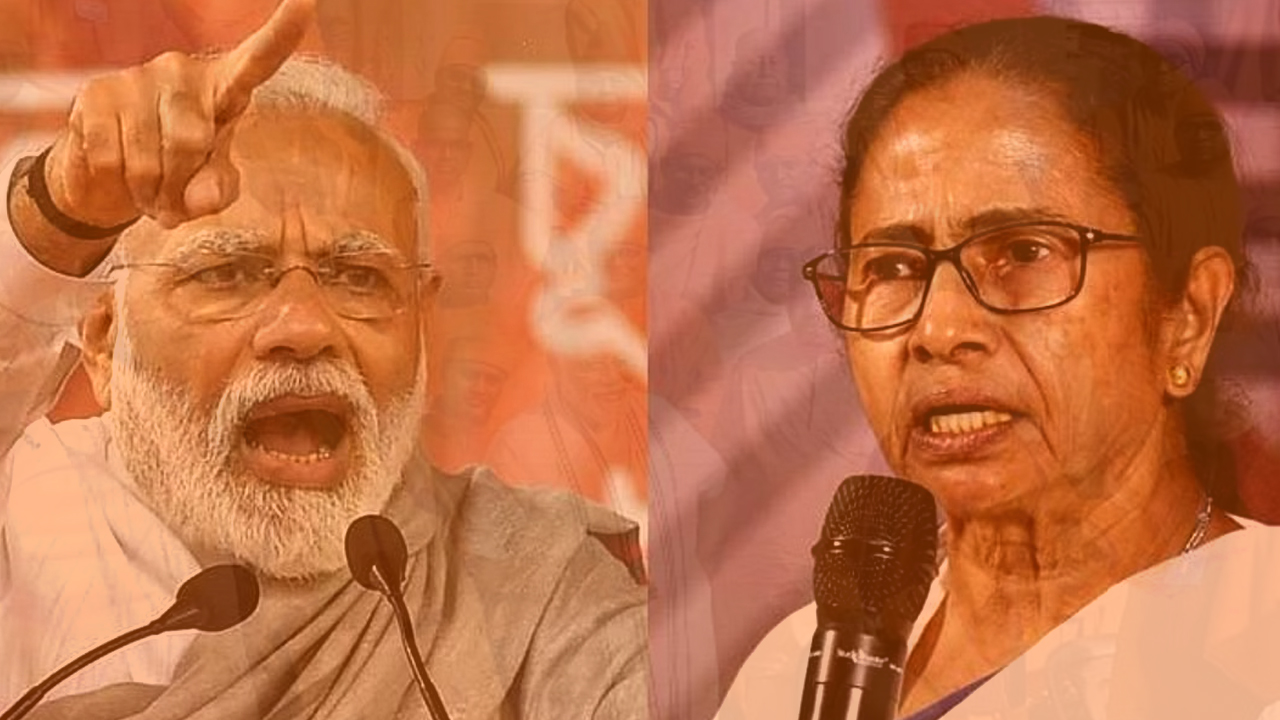

Recent utterances by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee decrying the alleged activities of monks of Ramakrishna Mission, Bharat Sevashram Sangha and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in favour of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2024 parliamentary elections have stirred a hornet’s nest.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi thundered at more than one election rally while visiting the state that “It is shameful that the TMC has taken up the onus of hurting the religious faith of Hindus in Bengal.” He accused that “The chief minister herself has been threatening the Hindu monks.”

Amit Malviya, “In-charge of BJP’s National Information & Technology Dept. Co-incharge West Bengal”, wielded his X handle to give out the call, “All Hindu organisations must come forward against Mamata’s open anti-Hindu rhetoric.”

Leaving aside the other two for the moment, let me say that I find it somewhat ironic that this controversy has made Ramakrishna Mission a sanctum of the Hindu faith and the BJP leaders have so earnestly taken upon themselves the sacred duty of saving it from sacrilege. The reason is, the Mission had long ago declared that it did not belong to the Hindu faith and fought a protracted legal battle to extricate itself from its fold. It is a different story though that it did not succeed in the end, but there is nothing on record that it has ever gone back on its claim.

To freshen up memories, I would like to place for the present readers’ perusal a report I wrote in the issue dated March 22, 1986 of the Economic and Political Weekly:

Religious Privilege vs Academic Freedom

A court case involving the Ramakrishna Mission has recently caused turbulence in academic and legal circles in West Bengal. Not only that, the judgments of the Calcutta High Court has taken even the ordinary devotees of the Mission by surprise. The surprise came in two phases. First, Justice BC Roy declared that the followers of the Mission are not Hindus, but constitute, under article 30(1) of the Indian Constitution, “a minority religious sect”. Later, Justice Chittotosh Mukherjee and Justice Bhagabati Prasad Mukherjee, comprising a Division Bench of the High Court, upheld the judgment. The Division Bench also opined that the Mission enjoys protection under Article 26 of the Constitution to preach and practise its religious faith in the educational institutions run by the Mission and to orient the courses of study, including science courses, taught in these institutions, in accordance with their religion.

The case concerned was in fact, a sequel to a long strife between the teachers of the Vivekananda Centenary (VC) College, Rahara and the authorities of the Ramakrishna Mission, spread over more than a decade. The VC College was established in 1963 with financial aid from the Central and state governments as a government-sponsored college. Initially, it was governed by an ad-hoc body. In 1969, a constitution came into force, according to which, the Mission had no other privilege than having three representatives in the governing body. But the Mission authorities were not quite satisfied with the arrangement. A service rule was introduced in 1975 which made the teachers employees of the Mission, and empowered the authorities to transfer them to any institution under the Ramakrishna Mission’s Boys’ Home or to terminate their service with three months’ notice. Besides these, the teachers required permission from the authorities to become members of any association or organisation. The governing body was virtually made a subcommittee under the Ramakrishna Mission Boys’ Home. The teachers of the VC College were able to get these regulations withdrawn on May 20, 1978, not before three years of agitation and having to counter threats and physical attacks.

The term of the old governing body expired on October 21, 1978, but it was never reconstituted according to rules. Instead, in 1980, Swami Sivamayananda was nominated to the post of Principal of the college by the Mission. Earlier, he had served in the Belur Vidyamandir, a branch of the Mission. The teachers looked upon this action as a gross violation of the West Bengal College Service Security Act, 1975 and the West Bengal College Service Commission Act, 1978. This again gave rise to a prolonged agitation by the teachers; In the face of a fifteen-day strike, the authorities closed down the college. But the teachers took over and ran it for 139 days from September 11, 1980. During the movement, the state government failed to spell out its stand on the matter. The state-wide organisation of college and university teachers, WBCUTA, too, remained silent. Only the Scientific Workers’ Forum, West Bengal, submitted a memorandum signed by 67 teachers, researchers and other science-workers to the chief minister on December 15, 1980. It supported the demands of the teachers of the VC College and called for a “science education free from religious control”.

On December 18, 1980, the teachers filed a petition in the High Court of Calcutta demanding the removal of the nominated Principal, reconstitution of the governing body, implementation of the West Bengal College Teachers’ Service Security Act, provident fund, pension, etc. The Mission authorities realised that the only way to claim immunity from the government rules was to establish themselves as a minority religious group. They acted accordingly.

After the High Court and the Division Bench had issued their judgments, the teachers of the VC College filed a petition in the Supreme Court in the first week of November, 1985. The Supreme Court, in its interim order on December 16, 1985, asked to maintain status quo according to the college constitution and also ordered that no fresh post should be created without the Court’s approval and no action should be taken against any teacher.

Another interesting development has now taken place. Professor GC Asnavi (formerly in the United Nations Service) of Pune, after reading in press reports that the Ramakrishna Mission has opted out of Hinduism, sent a letter to Justice PN Bhagawati, the Chief Justice of India, on December 16, 1985. He stated that he was an initiated disciple of the Mission, and had been aggrieved by this action of the Mission authorities. According to him, it had affected “millions of Hindus in general and many Hindu disciples of Shri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda” in particular. He argued that the postulation that “Ramakrishnaism” is a religion different from Hinduism was incorrect.

Whatever comes out of the case in the end, would have far-reaching implications not only on the characterisation of the Hindu religion, but on the more general and grave issue of how far religious privilege should be allowed to act upon academic freedom. If one studies the problem in depth, it seems that the Articles 26 and 30, in this respect, come into conflict with the principle of secularism maintained in the preamble and the principle of legal equality upheld by Article 14 of the Indian Constitution. Can the Supreme Court sort out the tangle? (Dutta, Nilanjan. 1986, ‘Religious Privilege vs Academic Freedom’, Economic and Political Weekly, 21(12): 476.)

The Supreme Court unknotted the tangle finally by reversing the High Court judgement on 2 July 1995 and ruling that it was indeed a Hindu organisation. It based its jurisprudence on the logic that Hinduism was inclusive enough to be able to hold a variety of paths and practices in its fold. It asserted that “to say or to hold that there came into existence Ramakrishna religion-a universal religion, apart and distinct from Hindu religion would, again be travesty of truth and reality.” (AIR 1995, SC 2089)

However, it has not evaded the eyes of legal researchers and commentators that “Interestingly, it was a mundane and entirely secular matter that led to these rather profound questions regarding the nature of Hinduism and Ramakrishna Mission’s ideology being raised at court.” (Mukherjee, Sipra. 2012, ‘The Curious Case of the Ramakrishna Mission: The Politics of Minority Identity’, Minority Studies, OUP India.)

Putting it more bluntly, we may ask, how durable is the foundation of faith of an institution that was willing to abandon its creed on such flimsy grounds as a dispute with its employees and how strong morally are those who defend it today with ostentatious valour?

Nilanjan Dutta is a human right activist and an independent journalist.