The poor health of asbestos factory workers highlights the need for health examinations of workers to be conducted by occupational disease health specialists from outside the factory. After bone-breaking hard work and risking their lives, the workers earn a paltry 6000-8000 per month. They are trapped in economic slavery.

By Nadeem Ansari, an Independent Journalist.

Dec 5, 2023

Maun Village in Mohanlalganj tehsil of Lucknow district, Uttar Pradesh, is home to the U.P. Asbestos Limited factory, which was established in 1973 on lands seized from local farmers to produce asbestos sheets.

Shatrughan Singh (68 years old), a resident of Darzi Tola in Maun village, worked in this factory from 1975-2009. He recalls that when land was acquired for establishing the factory in 1974, his five acres of agricultural land was also taken, and in return, he received a meagre compensation of only Rs 8,000.

During acquisition, he was assured that, in exchange for the seized land, he would be provided with a stable job and a good salary. Shatrughan’s father was a farmer, and he used to assist his father in cultivation before their land was acquired.

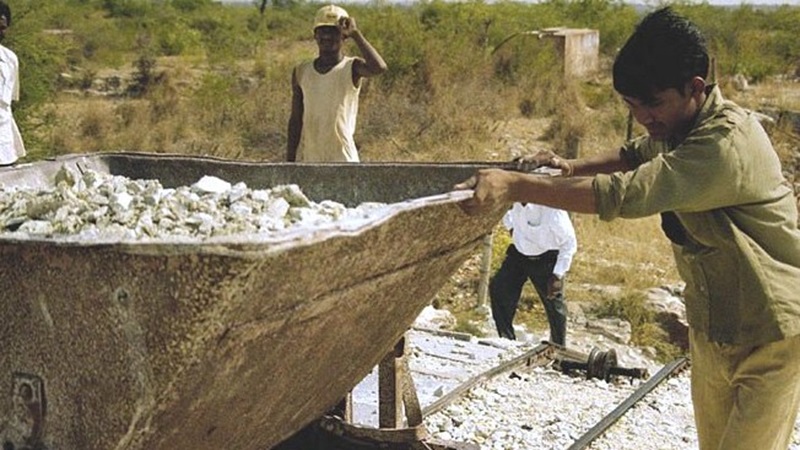

When he started working in the asbestos factory in 1975, he was assigned the task of loading asbestos-laden wagons with his hands, earning a monthly wage of just Rs 104. With deductions for every holiday, he struggled financially. After six months, his wage increased to Rs 250 per month. Later, he was assigned to operate machines and then to cut asbestos sheets.

In 2009, at the age of 54, as his health deteriorated, and work became challenging, the factory authorities pressured him to take voluntary retirement. To entice him, they offered a good severance package.

During retirement in 2009, Shri Shatrughan’s monthly salary was Rs 1,800. He received Rs 2 lakh as compensation for voluntary retirement. After that, he receives a pension of only Rs 975 per month.

An elderly person now, Shatrughan said, during those days, all work in the factory was done with hands. He started to suffer from respiratory problems and chest pain.

Later that pain spread all over his body. Now, he is dependent on medications for pain relief and breathing trouble.

Throughout his service years, he faced financial difficulties, and his health deteriorated. He mentions that even today, the roof of his house is covered with a pile of asbestos dust.

Jamuna Prasad (name changed) states that exposure to pressure gas has adversely affected his health. He uses a mask to protect himself from pressure gas. He has been working in the asbestos factory for 18 years. For 15 years his job was to throw cement in the kiln. For the past three years he has been grinding asbestos fibre. His daily wage is Rs. 250, and for every holiday, including Sundays, wage is deducted. Till ten years ago, the workers used to get jaggery daily to eat, after which it was stopped. For the last three years, only on Tuesdays, they are given chickpeas and jaggery.

Similar stories are shared by all the labourers who are working or have worked in the UPAL factory for a long time. Now the majority of the labourers in the factory are from Dalit community and landless workers.

Almost all the workers are suffering from breathing-trouble, chest pain and body-ache. Currently, the majority of the workers in the factory are temporary, earning around Rs. 200-250 per day. Most workers live under roofs made of asbestos sheets from the factory.

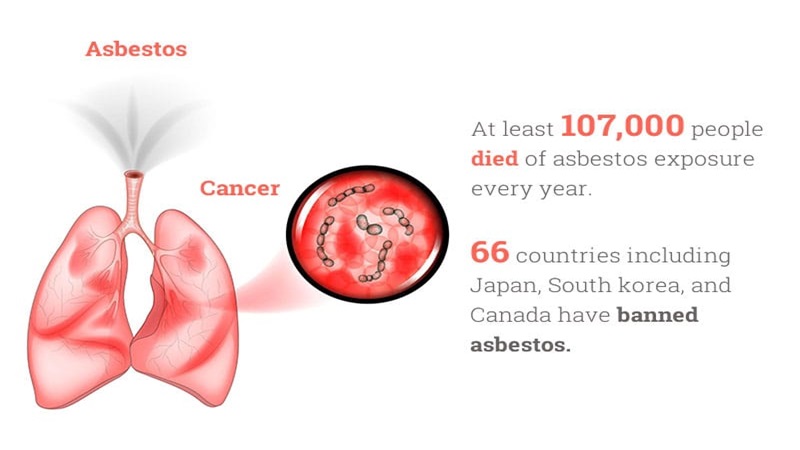

Every year, more than one lakh person die

Diseases affecting workers and their causes: The illness affecting these workers in the form of respiratory trouble and chest pain is not a common disease but it has devoured the lives of many labourers. Workers in the factory said that by the time the workers retire or shortly after retiring from the factory, they experience difficulty in breathing. Many complain of chest pain, have fever, vomit blood, and die.

These are actually symptoms of a disease caused by prolonged exposure to asbestos fibres, known as asbestosis.

Asbestosis is a disease caused by prolonged exposure to asbestos fibres. Fibrous particles and dust containing asbestos, when inhaled, get trapped in small air sacs within the lungs, where they cause damage to the lung tissues by creating scars.

Since asbestosis is a progressive disease that develops over time, its symptoms may remain hidden for many years after exposure. During this period, asbestos pollution would have already caused significant damage to the lung tissues, making the lungs stiff and less capable of expanding and contracting normally. Smoking exacerbates the damage, accelerating the progression of the disease.

Continued exposure to asbestos is dangerous. All forms of asbestos, including chrysotile, have been proven to be carcinogenic to humans. Asbestos exposure is a known cause of mesothelioma, lung cancer, and cancers affecting the larynx, ovaries, and other organs. Mesothelioma is an aggressive cancer, and life expectancy after diagnosis is often less than 12 months.

International efforts to prevent asbestos-related diseases include regulations set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the United States. OSHA has established a standard for asbestos exposure, stating that the permissible exposure limit for asbestos is 0.1 fibre per cubic centimetre of air, averaged over an 8-hour workday.

The World Health Organization (WHO) categorises all forms of asbestos as harmful, meaning they are carcinogenic to humans. More than 50 countries, excluding some major nations like India, China, and the United States, have banned asbestos mining, manufacturing, and use due to the associated health risks.

According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), asbestos-related diseases cause nearly 90,000 deaths worldwide each year. Despite the alarming picture, the use of asbestos continues in India, which remains one of the leading importers of raw asbestos, primarily from countries like Canada, Brazil, Russia, and Zimbabwe.

In India, asbestos mining takes place in states such as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. The state government has formulated rehabilitation and compensatory policies related to silicosis/asbestosis and its associated risks. However, these policies often fall short in adequately addressing the treatment, rehabilitation, and welfare of affected workers and their families.

While states like Uttar Pradesh may not have asbestos mines, but have factories producing asbestos sheets. Workers in these factories are at risk of developing asbestos fibre related diseases. Workers in these factories, who are at risk of contracting asbestosis, often do not have access to comprehensive health check-ups, and the government’s focus on their well-being, rehabilitation, and compensation is limited.

Lack of specific policies addressing asbestosis in the country

Even the deaths of workers due to asbestosis and the resulting helpless condition of their families goes unnoticed. There is no policy for workers in such factories who are affected by asbestosis disease.

The question is that when it has been established that wherever raw asbestos is stored, and inhalation of dust from asbestos fibres cause killer diseases like asbestosis, why is there no policy to regulate its use in factories. It is essential for the state of India to participate in international efforts to ban all types of mining, manufacturing, and use of asbestos to prevent the spread of this deadly disease among its citizens, which is also its responsibility towards them.

Welfare schemes for workers : Most workers in the factories have been working for years but are employed on a contract basis. The responsibility of providing social and economic security under the Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESI) lies with the employer, but the management has completely absolved itself from the responsibility by hiring them on a contract basis. The nature of work in the factory is permanent, but due to the contractual nature of employment, the labourers are completely deprived of any social security or employee welfare schemes..

Health check-ups are conducted monthly in the factory, but the results of the tests and examinations are not communicated to the workers. Most workers in the factories suffer from coughing, chest pain, and fever in the evening, but there is no provision for any medical treatment from the factory.

No trade union in this factory

The majority of workers in the factory come from the Dalit community, and there is no presence of any social organisation or trade union in this factory. According to local people in Maun, there is no presence in this factory of any organisation or trade union claiming to work for the rights of Dalits or workers.

The factory is only 25 kms from Lucknow – the state capital. But on talking with trade union leaders there, I realised they are unaware of the working conditions in this factory.

The retired workers told me that there used to be a union of Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh in the initial days. But the union never initiated any struggle for the rights of the workers.

Conclusion

The poor health of asbestos factory workers highlights the need for health examinations of workers to be conducted by occupational disease health specialists from outside the factory. After bone-breaking hard work and risking their lives, the workers earn a paltry 6000-8000 per month. They are trapped in economic slavery.

The responsibility of proving the diseases lingering within the workers in this factory as occupational disease falls on organisations that work on occupational health, and it is the duty of trade unions claiming to speak for workers to ensure that their labour-rights are protected.

Thus, coordination between public health organisations and trade unions is needed to address the health issues of U.P. Asbestos Limited factory workers and free them from economic servitude.

The article was originally published at Workers Unity.

Read the original article.