The following article is a response to an article by Prof. Avijit Pathak, published in the Indian Express on January 6, 2021. While this article is technically a response to the published views of one academic, the editorial collective at Notes on the Academy believe that his article echoes a sentiment shared by many in academia. Groundxero is republishing their response:

Liberalism is alive and well in the academy. In a recent article prompted by the protests that erupted following the inauguration of a statue of Vivekananda on the campus of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Prof. Avijit Pathak bemoans the collective failure to cultivate an “epistemological pluralism”. He writes:

“[G]iven the dominant political discourse prevalent in the country, some might think that the unveiling of the statue of Swami Vivekananda at the JNU campus is just a beginning; it is a step to “purify” the “Left-Ambedkarite” university, and bring it closer to our “nationalist” aspirations. However, as a teacher/wanderer with some sort of intellectual and emotional affinity with the campus, I seek to reflect on the ideal of a university beyond the much-used prism of the “left” vs “right” discourse.”

The suggestion here is that the dichotomy of left and right is a “prism” which refracts reality and occludes our vision; it follows, then, that we might see something more true about recent events in JNU if we set down this prism. Often, we have heard a similar sentiment echoed by our colleagues, especially in the sciences, where it takes a slightly different form: that our analyses and opinions should be unbiased and not infused with or infected by political ideology.

We disagree.

Have Gandhi, Tagore, and Aurobindo Been Sidelined?

Pathak writes:

“[I]t evolved some sort of intellectual snobbery and lost its connectedness with local intellectuals and diverse knowledge traditions. Moreover, at times, its radicalism became somewhat intolerant, or suspicious of all those who saw the world differently.

For instance, I have no hesitation in saying that the ideas of Gandhi, Tagore and Aurobindo didn’t get adequate importance; and any reference to texts like the Bhagavad Gita or the Upanishads was often condemned as “Brahminical”.”

We find it a bit absurd to suggest that Gandhi, Tagore, or Aurobindo are merely local cultural figures. All three occupy prominent positions in the dominant cultural imagination in the country, and their influence both within and without university spaces is palpable. There are, on the other hand, plenty of oral traditions in India – performers, writers, poets, and thinkers – that haven’t yet been introduced into the academic framing of Indian culture. The academic discourse often only takes them as examples and does not confer upon them the status enjoyed by these dominant figures.

This problem of representation manifests both in the syllabus, as we have just described, and also the university space itself. The fact remains that JNU, with all its claim to progressiveness, is heavily criticised even to this day by anti-caste activists for its lack of inclusiveness. We would understand if these facts were offered up as examples of academic elitism – this is, however, not done.

It is in fact the nature of the dominant sections of society to cry foul when any other perspective displaces their own central themes. It also performs the function of shifting the goal post to accommodate the existence of conservatives, to make any imaginations of the university palatable to reactionaries. The idea that fundamentally (often violently) contradictory positions can be accommodated and discussed without bias or preference, and that this demonstrates the virtue of tolerance, is paradigmatic of liberalism. It is also not new: privileged spheres have replicated this strategy, without showing any hints of fatigue, whenever the opportunity arose. To give the reader a sense of just how jarring these contradictions can be, observe that Prof. Pathak writes:

“I look at Swami Vivekananda. I begin to hear the marvellous speech he delivered at the Chicago Religious Congress — the Upanishadic message of fundamental oneness amid differences […] with Ambedkar, I open my eyes, and give my consent to the project of annihilating caste.” (Emphasis ours.)

This is usefully contrasted against this excerpt from Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste:

“The Hindus hold to the sacredness of the social order. Caste has a divine basis. You must therefore destroy the sacredness and divinity with which caste has become invested. In the last analysis, this means you must destroy the authority of the shastras and the Vedas.” (Emphasis ours.)

If liberal professors can accept these two ideas simultaneously, and assign equal value to them both, they are demonstrating a plurality of thought that is unattainable – indeed, undesirable – to us. Indeed, we cannot help but feel that a bias in this context is not a bad thing for a university, provided the bias is dictated by firm ideological and methodological choices, as we believe the case is with JNU.

For these reasons, we believe it is not the time to cry foul that the Vedanta or the Upanishads or Kalidasa aren’t studied. Rather, we believe that we stand more to gain by understanding why it is that entire departments dedicated to the study of philosophy, science, society, politics, and economics, relegate these texts to the status they currently enjoy in academic discourse.

The Political Context for Plurality

We believe that it is important to place the demand for “plurality of thought” in the broader context of the political atmosphere outside university campuses. Prof. Pathak’s op-ed was written in response to popular resistance to a religious statue placed in a bastion of left-wing and Ambedkarite political engagement. We can’t help but wonder: is this really a good example of the psychology of revenge? For contrast, there were so many activists arrested in the last year that one has to consult a list to keep track. Isn’t the vindictiveness with which the government has targeted activists, scholars, and lawyers fighting for the rights and dignity of common people more deserving of this characterisation?

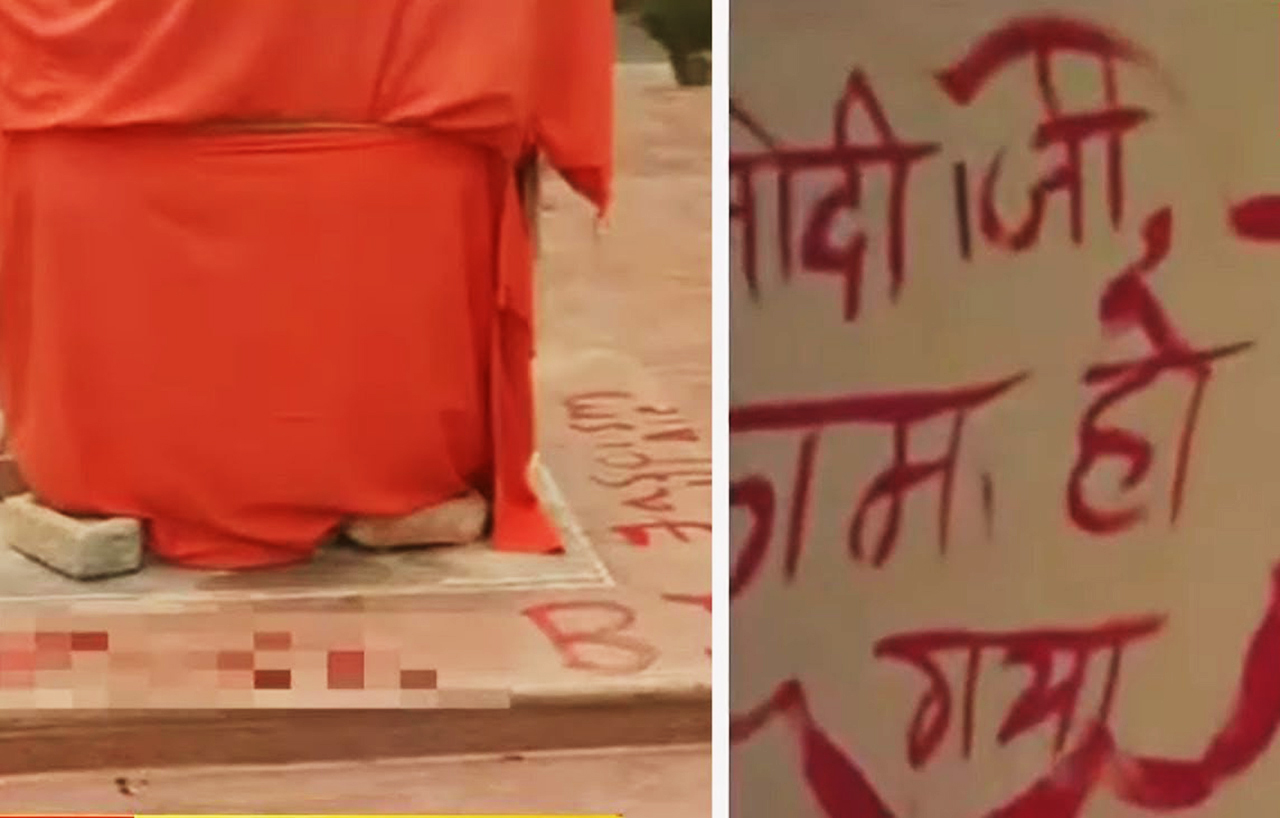

The protests following the installation of Vivenkanada’s statue in JNU are not the issue. The issue is, rather, the intent behind the decision to place this statue here. As the author mentions in the end – the ideal of a university being a place where one has the freedom to learn about different/opposing points of view is destroyed by the “psychology of revenge”. JNU is being bullied by the central government, with the powers that be hell bent at framing the students as the principal antagonists of Indian society.

In a political atmosphere that embraces and mythologises reactionaries, that takes a leaf out of the fascist playbook by resurrecting fever dreams of a return to a glorious past, to constantly emphasise the importance of listening to both sides often leads to radical and emancipatory thought being sidelined in favour of the dominant Hindu ideology, which already finds ample support in the society.

Here we face the most significant problem with the ideas that Prof. Pathak’s op-ed. Taken without reference to the sociopolitical reality we occupy, it is perfectly uncontroversial to ask that we collectively reclaim the spirit of “seekers and wanderers, continually learning and unlearning with openness, fearlessness and a dialogic spirit.” In the space of ideas, it is likely that these exhortations are acceptable to all. Once we return to reality, however, we find that really existing anti-caste and anti-capitalist activism faces extraordinary challenges: a reactionary public stirred into a frenzy by a majoritarian right-wing political party and crony-capitalist industries that enjoy the full support of a violent and vengeful state. In this context, that JNU supplies a countervailing tendency should be celebrated and bolstered, not knee-capped by demanding that it be more accommodating of “those who saw the world differently.”

Further, even if we are interested in finding an authentic form of intellectual wandering, it is counter-productive to frame it in terms of giving equal weight to both sides of a left-right binary. This binary is socially constructed, a reality we have all been witness to over the last decade as figures like Gandhi went from the established centre to its left. What is considered “left” and “right” depends on the society we live in, on the predilections of the ruling class and the intelligentsia and driven home by corporate-owned mainstream media. Why, if we are interested in being intellectual wanderers, should we yoke our thoughts to these forces?

Wandering and seeking does not become any less free if one doesn’t walk into the ocean, no matter the strength and extent of the moneyed and feudal interests insisting that the ocean is as solid as land.

Notes on the Academy is a magazine that attempts to critically evaluate academic institutions and culture. You can follow them on Twitter @notesacad and on Instagram @notacademy.in.