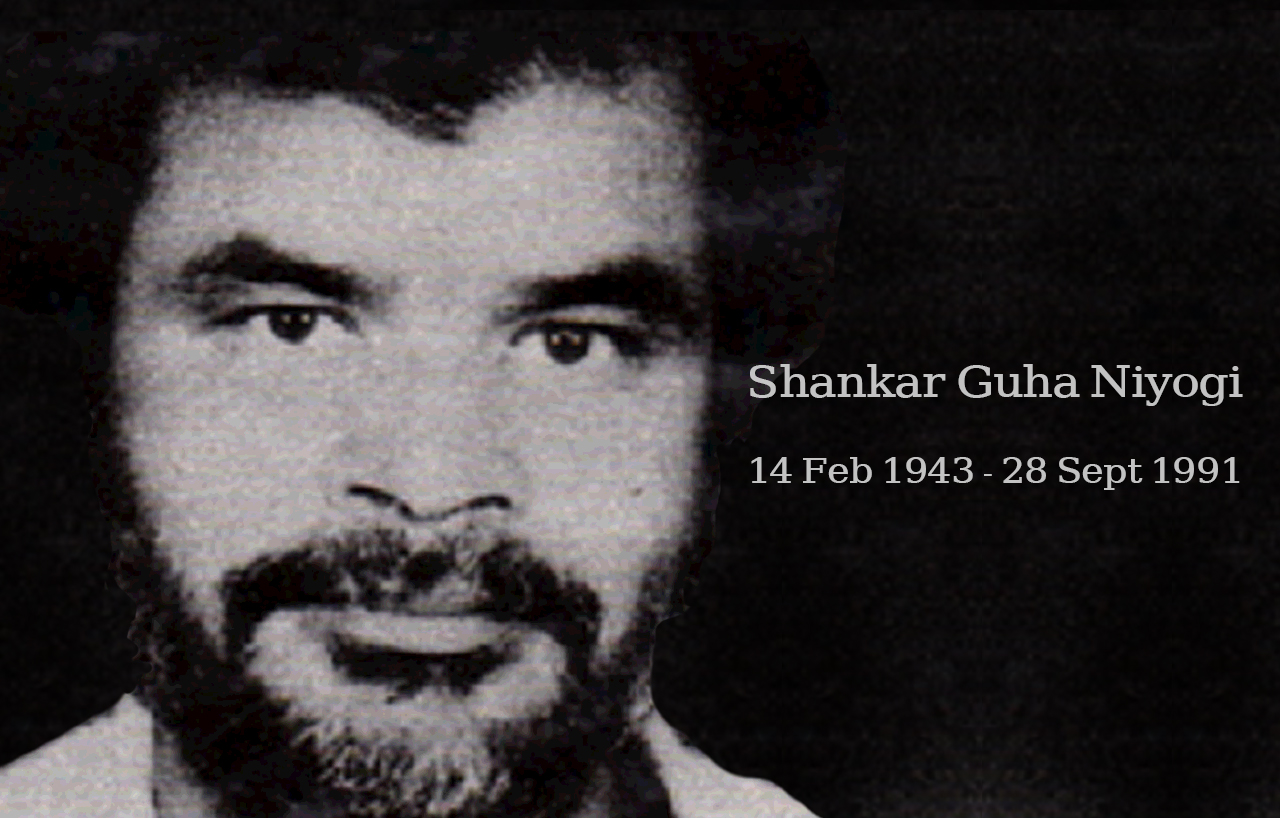

On Com. Shankar Guha Niyogi’s 29th martyrdom day, an extract from Dr Punyabrata Gun’s memoir “Struggle And Create: My Days With Com. Shankar Guha Niyogi”, translated from Bengali to English by Anirban Biswas.

An extract from NIYOGI AND HIS MISSION (Chapter 1) by Dr Punyabrata Gun’s memoir “Struggle And Create: My Days With Com. Shankar Guha Niyogi”.

I first came to know of Shankar Guha Niyogi and the Chhattishgarh movement in 1979, when I was a first-year student of Medical College. As far as I can recollect, my source of information was a journal named Curtain. In 1982, when I was studying in the third year, a senior in my organization told me of the ‘safai’ (cleansing) movement of the Chhattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh, the Shaheed Dispensary and the dream of building the Shaheed Hospital. He was Dr. Pabitra Guha, who had worked for a few months with the CMSS in 1981. (After the martyrdom of Niyogi, he resigned his job in 1992 and went back to the Shaheed Hospital, and remained there till 1994. He lives in Dalli-Rajhara as yet.) That tale made Dalli-Rajhara a dreamland of mine, and I began to dream of working with the CMSS.

I first met the architect of my dreamland in the first week of July 1985 in Bhopal. The gas victims of Bhopal laid the foundation stone of a people’s hospital on the premises of the Union Carbide factory. The work for the people’s health centre began with the help of junior doctors from Kolkata and Bombay. There the gas-affected people were administered the sodium thiosulphate injection, an antidote to poisonous gas, and the improvement in their symptoms was registered. Improvement in the symptoms of the gas-affected people with thiosulphate implied the existence of cyanide in poisonous gas, which enhanced the criminal culpability of the Union Carbide. Hence, the state launched its terrorizing operation on the night of 24 June. The doctors, health workers and organizers were arrested. I went, along with my junior friend Dr Jyotirmay Samajdar, from Kolkata in order to resume the functioning of the closed health centre. The day when the prisoners were to be released on bail—the sun was setting over a hillock behind the Bhopal Jail—the assembled people were responding to a slogan raised by a tall man dressed in shabby pajama and kurta “Jail ka taala tutega, hamara sathi chhutega”(locks of the prison will be smashed and our comrades will come out). That person was Shankar Guha Niyogi, leader of CMM. I approached him and informed him of my dream of working in his movement. He said in Bangla with a Hindi accent, “Come, we are thinking of setting up another hospital in Rajnandgaon…”

In December 1986, I finally decided to leave Kolkata for Dalli-Rajhara. While at college, I was involved in pro-change students’ politics and dreamt of getting integrated with workers and peasants. But my theoretical knowledge of the politics of social transformation was almost zero. When I met Niyogi, who was always busy, I looked at him, listened to his words and tried to comprehend them. It is Niyogi ji who was the principal teacher of politics in my life.

It was 1st or 2nd January 1987. Workers of Dalli mines were on a strike. The management of the Bhilai Steel Plant took this opportunity to violate the agreement of not pushing mechanization and to run dumpers. While trying to resist it, 21 workers or worker leaders were injured by the CISF’s lathi-charge. Some received wounds on their heads and some had their hands fractured. They were writhing with pain when they were brought to the Shaheed hospital. Pain-killing injections did not produce the desired result. Hearing the news, Niyogi came rushing to the spot, gnashing his teeth in anger. He caressed the wounded with affectionate hands. I saw with wonder that the touch of Niyogi’s hands did what the pain-kiling injections had failed to do; the wounded persons forgot their pain and quietened. (The spectacle seemed to be like that of a child, taken in his mother’s lap, forgetting its stomach-ache.) Then he, with swift steps, came out of the hospital and drove his jeep towards the mines. Later we heard that Niyogi, bursting with anger, seized the commandant of the CISF by his collar and the CISF jawans pointed their guns at him. Perhaps Niyogi would have been shot but for the intervention of a high-level police officer who came in between. That day, I could fathom the depth of his feeling towards his comrades, his extraordinary courage and class-hatred. I also realized the intensity of love of the people for a real leader.

Niyogi did not write any autobiography, and it does not seem probable that he would have written anything like that even if he had found time for it. He never told anybody about his past life in a way that would enable the listener to write his authorized biography. But I heard many times, as did others, tales of various phases of his life, fragments of various episodes from 1969 to the end of the Emergency in 1977

Shankar Guha Niyogi (his original name is not Shankar, but Dhiresh) was born in a middle class family. His father’s name was Heramba Kumar and mother’s name Kalyani. He received his primary education in the village of Jamunamukh of Naogaon district of Assam, and the beautiful natural scenario of Assam made him a lover of nature. He received his high school education when he was living with his uncle in the Sanktoria coalfield area near Asansol. Looking closely at the lives of the coal-miners, he began to understand how the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. While studying the Intermediate Science Course in Jalpaiguri, he got involved in the student movement and became a devoted worker of Students’ Federation of India. The wave of the food movement all over Bengal in 1959 swept him away. He got the membership of the undivided Communist Party of India as a skillful student organizer. As he was intensely involved in student politics, his results in the examination were not good. Yet he was allotted a seat for studying engineering in Jalpaiguri on the strength of family recommendation. But he considered it an undue privilege and deserted his home.

It was the year 1961, when it was not difficult to find employment in the Bhilai Steel Plant (BSP. I heard from Niyogi that the recruiting officer of the plant used to sit at a table on the Durg railway station platform, the purpose being to recruit for the plant those who had come from outside to seek employment. Dhiresh’s age was then a few months less than eighteen, which was the minimum age for employment. So he had to wait for some time. Then he underwent a training course, after which he was employed as a skilled worker at the coke-oven department of the plant. He had nursed a desire for higher education, and hence began to study the BSc and AMIE courses at Durg’s science college as a private student. Dhiresh gave leadership to the student movement of that college. Sweepers of the Durg municipality, informed of this skillful leader, came to him, and realized their demands after a successful strike under his leadership. The recognized union of the steel plant was affiliated to the INTUC. The next largest union was that of the AITUC. Niyogi, while remaining with the AITUC, went on organizing the workers independently for the solution of their various problems.

In 1964, the CPI split into two, and Dhiresh joined the CPI (M). At that time, he studied classical Marxism-Leninism under the guidance of Dr BS Yadu, a veteran communist physician. The Naxalbari uprising of 1967 created a stir in Madhya Pradesh too, and almost all the CPI (M) activists of this province were influenced by it. Dhiresh came in contact with the All-India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries. After the formation of the CPI (M-L) on 22 April 1969, he was associated with it for some time. But failure to adapt his own activities to the party line of boycott of mass organizations and the mass line led to his expulsion from the party. (It may be mentioned that the decision to expel Niyogi was taken in the presence of an elderly leader and subsequently, that leader too opposed the party line on the same question.)

Meanwhile, some events had taken place. Dhiresh lost his job after leading the first successful strike in the BSP. On the other hand, the police, having branded him a Naxalite, was looking for him. At that time, he went underground and began to take his thoughts to the ordinary workers by means of a Hindi weekly. Inspired by Lenin’s Iskra, he named the weekly Sphulinga (Spark). Side-by-side, he began preparations for going to the villages. During this period, he came to the realization that for the victory of the working class movement, it was essential to form a bond between this class and the exploited Chhattisgarhi nationality. He wrote a booklet on the nationality problem of Chhattisgarh, which was proscribed by the police just as it was coming to Chhattisgarh after getting printed in Maharashtra.

In order to know Chhattisgarh and its people and to be integrated with them, Niyogi, since 1968, had traveled and lived incognito in the villages. Sometimes he assumed the identity of a seller of goats, buying goats in the villages and selling them in Durg and Bhilai. He could in this way maintain his contacts with his comrades there. Sometimes he was a peddler, sometimes a fisherman or a PWD labourer. Alongside, he continued the work of organizing the people through movements, e.g. movement for the construction of the Daihan dam, movement of the peasants of Balod for irrigation water, movement of the adivasis against the construction of the Mongra dam.

In 1971, he got employment as a contract labourer in Danitola Quartzite mine of the BSP; the skilled worker of coke-oven was now grinding stones, wearing shorts. This is the period when he assumed the name Shankar by which he became known widely. Here he made his acquaintance with his future wife Asha, daughter of his co-labourer Siyaram. The first miners’ union organized by him was also located in Danitola, although under the banner of the AITUC. Before his arrest under the MISA during Emergency in 1975, Niyogi’s organizational activities were in Danitola.

The largest iron ore mines of the BSP were situated in Dalli-Rajhara. When Niyogi was imprisoned in Raipur Jail, contract miners of Dalli-Rajhara were vigorously engaged in a spontaneous movement. The leadership of the INTUC and the AITUC entered into an unjust agreement with the BSP management, according to which, permanent workers and contract labourers were to receive Rs 308 and Rs 70 per head respectively, although both categories of workers did the same type of work. Workers came out of the two unions in protest against this unjust agreement. It was the last phase of the Emergency. On 3 March, workers stopped work and started an indefinite dharna in the Lal Maidan. They were looking for an able commander who could lead them. Seeing the militant attitude of the workers, no union leader belonging to the CITU, HMS or BMS—dared to face them. A few days later, as the Emergency came to an end, Shankar was released from prison. The distance between Dalli-Rajhara and Danitola is only 22 kilometers. Some workers, who had come out of the AITUC, knew Niyogi as an honest, fighting leader. Hence a team of representatives of Dalli-Rajhara workers went to Danitola in order to request him to give leadership to their movement. Niyogi, at their invitation, came to Dalli-Rajhara, and the independent organization of contract miners, Chhattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh (CMSS) was formed. The flag of the new union was red-green, red standing for workers’ self-sacrifice and green for the peasantry.

The first struggle of miners under Shankar Guha Niyogi’s leadership was a struggle for dignity; they would not obey the agreement signed by the leaders who were lackeys of the management. They accepted financial losses and took Rs 50 each, instead of Rs 70, as bonus from the management and contractors of the steel plant.

In May 1977, began the movement for idle wage (the wage that a worker is entitled to, when the employer cannot provide him with work) and for Rs 100 as house repairing allowance. The pressure of the movement compelled the management and contractors to yield to these two demands in presence of the officers of the labour department. But on 1 June, when the workers went to take payment of the repairing allowance, the contractors refused to pay it. The workers again went on strike.

On the night of 2nd June, the next day, two jeeploads of policemen came to arrest Niyogi. They arrested Niyogi from the hovel of the union, and a jeep sped away with Niyogi. Before the other jeep started, workers, awakened from their sleep, surrounded the remaining policemen, demanding the release of their leader. In order to break the encirclement, the police opened fire, killing seven persons, including Anasuya Bai, a woman worker, and Sudama, a boy. But this did not prove enough for them to get out of the encirclement. Finally, on 3 June, a large police contingent arrived from Durg, killed four more workers and rescued the encircled policemen.

But police atrocities failed to put down the workers’ movement. After a continuous strike of as many as 18 days, the mine management and the contractors again agreed to the demands of the workers. Niyogi was released from prison.

The enthusiasm generated by this victory led to the formation of branches of the CMSS in other captive mines of the BSP—Danitola, Nandini, Hirri. All the branches together launched another wave of movement with further victories.

Dalli-Rajhara falls within the district of Durg, and the neighbouring district is Bastar. The authorities took the initiative of full mechanization of the Bailadila iron-ore mines of Bastar, the inevitable consequence of which would be retrenchment of workers. On 5 April, 1978 the police of the Janata Government opened fire on the workers struggling under the leadership of the AITUC to resist mechanization. Workers of Dalli-Rajhara stood by these struggling fellows. Side by side, Niyogi made Dalli-Rajhara workers aware of the impending danger of mechanization. The workers started the movement against mechanization, and compelled the management to accept the proposal of semi-mechanization, which would raise the quantity and quality of output without retrenching workers. They resisted mechanization till 1994. (In 1994, one section of the leadership behaved treacherously with the workers and handed over the Dalli mines to the management for full mechanization.)

Successive victories of the union in economic movements led to large increases in the daily wages of the workers of Dalli-Rajhara. But that scarcely had any impact on their standards of living. Rather the adivasi workers increased their expenditure on alcohol. Niyogi asked, “Should the blood of martyrs then go down the drain of the wine shop?” The union initiated a novel sharab bandi (anti-liquor) movement, which freed about one hundred thousand persons from this intoxicating habit. However, while continuing this movement, he was imprisoned under the National Security Act.

Niyogi gave the trade union movement a new dimension. So long, no established trade union did anything except demanding higher pay or bonus or replying to charge-sheets. In other words, trade union activities covered only those subjects that were related with the work places of the workers. Niyogi held that a trade union’s activity should not be confined to eight hours’ (work time’s) issues, it has to deal with ‘twenty-four hour’ issues. With this idea, the new union launched many new experiments in Dalli-Rajhara.

Mohalla Committes were set up in order to improve the housing conditions of the workers. In the schools run by the BSP, there was no provision for education of the children of contract labourers. Six primary schools were set up for these children under the leadership of the union, and an adult education programme for illiterate workers was undertaken. The pressure of the movement for education compelled the management to set up a number of primary, secondary and higher secondary schools. The health movement started in the form of cleansing (safai) movement. On 26 January 1982, the Shaheed Dispensary started functioning. On the Shaheed Divas (martyr’s day) of 1983, the Shaheed Hospital was inaugurated. For the pastime of the workers and for the expansion of a healthy culture, naya anjor (morning sunshine) cultural troupe was set up. The Shaheed Sudama Football Club and the Red-Green Athletic Club were formed for the cultivation of health. The Mahila Mukti Morcha was formed for women’s liberation movement. The CMM was built up with the aim of freeing Chhattisgarh from exploitation and for setting up the worker-peasant raj in Chhattisgarh. A model afforestation programme was implemented behind the union premises as a challenge to the anti-people forest policy of the government.

Attracted by the novel leadership of Niyogi, people inhabiting the vast stretches of Chhattisgarh began to take up the red-green flag. In those days Chhattisgarh was comprised of seven districts of Madhya Pradesh. In five among them, namely Durg, Bastar, Rajnandgaon, Raipur and Bilaspur, the organization and movement of the Mukti Morcha spread rapidly. Among those who fought under the banner of the Morcha were the workers of Bengal-Nagpur Cotton Mill of Rajnadgaon, the oldest factory of Chhattisgarh. On 12 September 1984, the police fired on them to put down their movement. Four workers courted martyrdom, but the movement was victorious.

The last struggle fought under Niyogi’s leadership was the Bhilai workers’ struggle. Bhilai was the centre of exploitation of workers in Chhattisgarh. The struggle started from there, and it drove the factory owners into panic. Yet the demands were apparently very ordinary—living wages (salaries for minimum livelihood), permanent jobs in permanent industries, right to be organized in unions. Chhattisgarh, which is rich in mineral, forest and water resources, was also the supplier of cheap labour. The upshot of acceptance of such demands was hence far-reaching and dreadful to the owners. So, the police, the administration and almost all the political parties joined hands to crush the movement.

The police and ruffians were employed to attack. Niyogi was kept in prison from 4 February 1991 to 3 April 1991 on the strength of various old warrants. Attempts were made to extern him from the five districts. But nothing could crush the movement. In order to mobilise public opinion in support of the movement, a large band of workers, led by Niyogi, went to Delhi and gave a memorandum to the President and the Prime Minister. A fortnight later, on 28 September, secret assassins hired by the owners murdered Niyogi.

Niyogi had come to know of the conspiracy to murder him much earlier. He noted it in his diary and told of it in a cassette. Yet he was resolute in the face of approaching and inevitable death. The reason was: “Everybody must die, so will I, today or tomorrow….I wish to set up a system on this earth where there will be no exploitation….I love this beautiful earth, and love my duty even more. I must fulfill the responsibility I have shouldered…. Our movement cannot be crushed by killing me.”

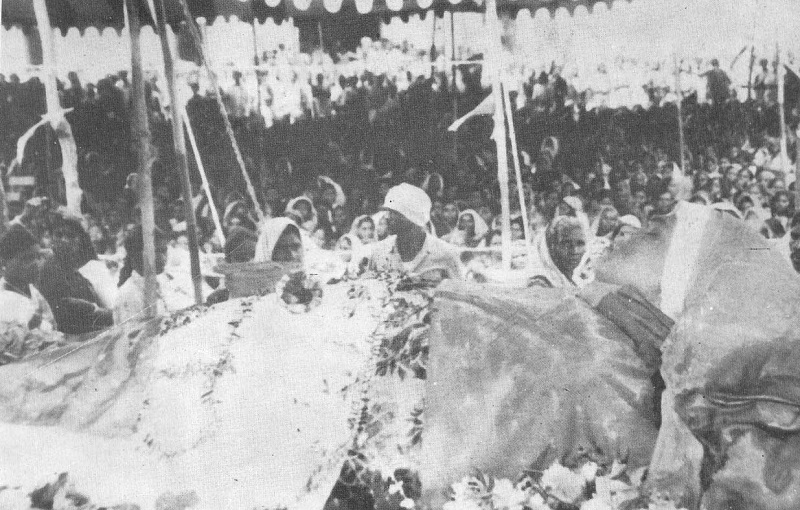

On 28 September1991, I, along with three worker comrades, brought down his blood-drenched corpse, from the table of the morgue of Durg. Nine hours after his death had already elapsed; yet fresh red blood was streaming from the bullet wounds on his back. Shankar Guha Niyogi, my leader, my comrade, my teacher, became a martyr. We covered the corpse of our heroic comrade with the red-green flags of the CMM.

I was with the corpse from 28 to 29 September. Six shots from an indigenous pistol pierced the back and went into the heart, but there was no sign of pain. The visionary, my leader was as if dreaming with a light smile. It seemed that if I called, ‘Niyogiji’, he would open his eyes and ask, “Doctor Sa’ab, what’s the news?”

- Link to the full chapter:

“Struggle And Create: My Days With Com. Shankar Guha Niyogi”: Chapter 1- Niyogi And His Mission

- To learn about Shankar Guha Niyogi’s life, his struggles and his theory of ‘Struggle & Creation’, you may read a book written and edited by Dr Punyabrata Gun.