Approaching the documentary as a sociological text, Zeeshan Husain discuss what he found to be the most important facets of the Dalit movement portrayed in the film.

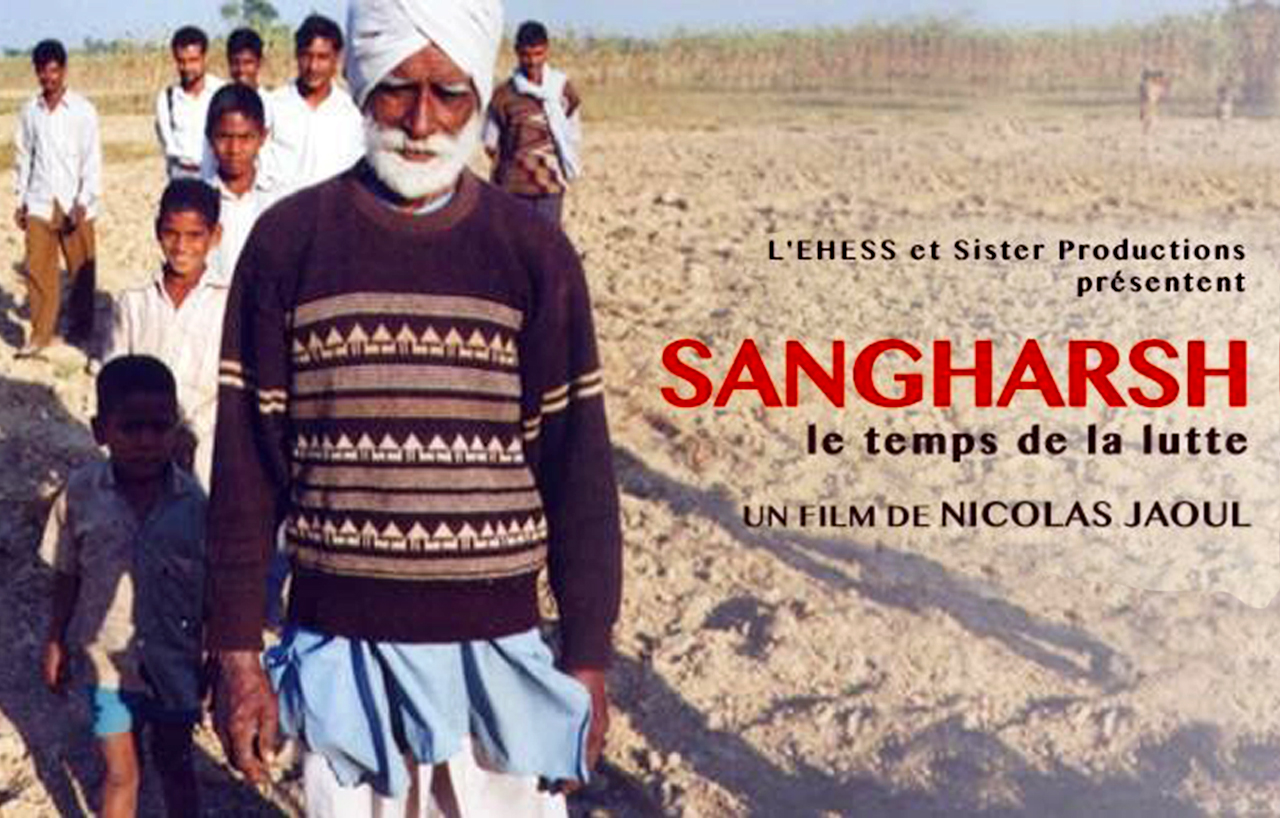

Sangharsh, meaning strife, is a film which deals with the Dalit movement in the late 1990s. The film takes place in Kanpur city and nearby villages. The film was made by French anthropologist Nicolas Jaoul, while he was doing fieldwork for his PhD between 1997 – 2001. The protagonist of the film is a Dalit activist named Dhaniram, an active member of the Dalit Panthers who was in his thirties at the time. The film revolves around his activities, but is not limited to just him. It takes us to the activities of few other activists, who are friends of Dhaniram. All his comrades-in-arms would call him ‘the Dhaniram Panther’. Jaoul uses the lives and work of these activists as an entry point to investigate the activities of the Dalit Panthers of Kanpur and teases out the most poignant contributions of the Dalit Panthers of Kanpur in particular, and the Dalit movement in Uttar Pradesh (UP) in general. Being a student of the Dalit movement in UP, I found the film to be fresh in its arguments, which are often glossed over by many social scientists. I approach the film as a sociological text. In this essay, I will discuss what I found to be the most important facets of the Dalit movement portrayed in the film.

The key point which the film makes is that the Dalit movement does not exclusively revolve around the activities of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). That which has been going on at the grassroots-level is much more complex than any simplistic understanding of the BSP would lead us to believe. One shot in the film shows us Dhaniram listening to Subhashini Ali, a former Member of Parliament from Kanpur, criticising the BSP’s electoral calculations for securing votes which restricts it from truly acting in favour of Dalits. What the film conveys is the idea that the Dalit Panthers are working for the upliftment of the Dalits at the grassroot-level without getting any limelight or recognition from the corridors of power. Like Waghmore (2013), Jaoul also tells us that the defeat and victory of the BSP does not affect the local-level small-group or individual-centric Dalit movements continually happening across Kanpur city and its surrounding districts. The Dalit Panthers kept on working for the upliftment of Dalits, unconcerned with the rise and fall of the BSP.

The dominant narrative formed by Savarnas (Hindu upper castes) claims that Dalits have been instigating caste consciousness among Hindus. The film, rightly, portrays Dalit Panther activists fighting against casteism, which is not only rampant at the level of physical assault, but also of structural exclusion. We see how some landlords physically assaulted Dalits when the latter refused to serve the former without being paid, a state of servility in which they have remained for generations. Historical research by Irfan Habib (2007) and others show that most of the present Dalits were slaves since at least early-medieval times. Abuse, be it physical, verbal, or even sexual, were common in UP until the 1980s. Indeed, caste(ism) as a problem does not remain limited to society, it equally penetrates polity. We see, at various instances, poor Dalit men telling us that even the police side with Brahmins and Thakurs who have been landlords since British times (Hasan, 1988). In one shot we see that although the Panthers were marching peacefully, police personnel tried to stop the march. This is not easy to infer when Jaoul shows us Dalits voting freely from the influence and fear of the dominant castes. The Panthers were encouraging Dalits to leave the Hindu fold and all the social evils associated with it. All the activists favour a conversion to Buddhism as a journey from humiliation to dignity. The camera moves to a Valmiki basti where various superstitious Hindu rituals are being carried out, when a child comes and says coyly, “I won’t do such rituals. I am educated.”

I would urge the reader to watch the film for two very important reasons. The Dalit movement is not only against caste(ism), but also against communalism and patriarchy. Casteism, communalism, and patriarchy might appear independent of each other but, as I understand it, these are three sides of a triangle we call Indian society. Dhaniram Panther understands this very well. His supporters tells us, “Dalit Musalman karo Vichar, Kab tak sahoge atyachar? (Dalits, Muslims, think a little! For how long will you suffer injustice?)” which signifies Dalits and Muslims must unite to fight against atrocities and injustice.

The film has two instances where the Panthers take a strong stand against communalism by Hindutva forces. At one moment in the film a boy in his late teens tells us how Brahmins and Thakurs have looted Dalits for centuries. The boy lives in the Dalit Panthers’ headquarters, in a slum inhabited mostly by Dalits and Muslims, something which is common across Indian cities. The teenager describes his version of communal riots happening in the background,

‘They even demolished the temples. The police, or maybe the Brahmins themselves. Just to frame the Muslims. So that the fight between Hindus and Muslims starts again. See our neighbors, they are Muslims. We eat at their place and they also come to eat at ours. There is no such hate between us… Because we are Buddhists’.

He considers Muslims as his closest allies against the forces of Brahmanism. Similarly, another comrade of Dhaniram named Dev Kumar has launched a protracted struggle against communalism in the Valmiki neighbourhoods, a caste to which he also belongs. He speaks to them of Hinduism as a garb adopted by Brahmanism to hide itself. Explaining the anti-Muslim riots, he says:

“Why should we fight against the Muslims? They’re not responsible for our present situation. The upper caste lobby doesn’t allow the Muslims to prosper. Nor does it want the Untouchables to rise. Therefore they interfere between the two so that Untouchables and Muslims fight among themselves. This way they are sure to keep on making profit.”

The reader may be aware of the fact that Dalits (Buddhists) and Muslims are two of the poorest groups in India (Thorat and Ahmad 2015) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) always pits Hindu Scheduled Castes (SCs) like Khatiks and Valmikis against Muslims in urban UP. Dhaniram and all his associates tell us unanimously that Ambedkarism is necessarily against communalism. (Jaoul, 2012).

Another point which is not well known is that the Dalit movement’s commitment to women’s liberation from ‘Brahmanical patriarchy’, that is, sexual subjugation of women to maintain caste purity and reproduce caste hierarchy. We see in the film many (Dalit) women attending processions and meetings by the Panthers with hand-drawn blue coloured fans with the picture of an elephant, the BSP’s electoral symbol. We know how Brahmin women sympathetic to the RSS are compelled to marry within their own Brahmin gotra (sub-caste) as a religious obligation (Bacchetta, 1999). One of Dhaniram’s comrades is sharp enough to understand this and articulate enough to say as much. “Ambedkar gave women the right to education; whether Brahmin or Dalit women”, he tells a crowd. This statement itself is extremely radical within the Hindu social order as women and Shudras (lower castes like SCs and Other Backward Castes) are not allowed to pursue education as per the Manusmriti, a canonical text of Hinduism. The Kanpur Panthers convinces us that the issue of casteism cannot be solved without solving the associated issues of communalism and patriarchy.

Sangharsh as a film and Jaoul as a film-maker succeed in showing that the Dalit Panthers movement of the late 1990s in Kanpur was meant not only for the Dalits of Kanpur but also for Muslims and women, and for that matter, everyone across India. There was just one thing missing – the position of backward classes in the worldview of the Dalit Panthers movement. Considered as Shudras (signifying low social class in the Hindu order) and victims of Brahminism themselves, they are also an economically backward section of the Hindu social order. There is a passing mention of a landlord from the Kurmi caste physically assaulting Dalit agricultural labourers. Until Mulayam Singh was active in politics, many backward classes were part of the lower caste assertion but now the winds are, sadly, blowing in favour of the BJP (read Brahminism). Nevertheless, the film convinces us that the question of caste is not a hurdle merely for Dalits but also an impediment to peace, harmony, and development in India. It is a hurdle for humanity as a whole. And the Sangharsh is still on to achieve that end.

Works Cited

Bacchetta, Paola. “Militant Hindu Nationalist Women Reimagine Themselves: Notes on mechanisms of expansion/ adjustment.” Journal of Women’s History, Vol 10 No 4 (Winter) 1999: 126-147.

Hasan, Zoya. “Power and Mobilisation: Patterns of Resilience and Change in Uttar Pradesh Politics.” In Dominance and State Power in Modern India: Decline of a Social Order Vol. 1, by Francine F Frankel and MSA Rao, 133-203. New Delhi: Oxford Univerty Press, 1988.

Jaoul, Nicolas. “The making of a political stronghold: A Dalit neighbourhood’s exit from the Hindu Nationalist Riot System.” Ethnography (Sage) 13, no. 1 (2012): 102-116.

Thorat, Sukhadeo, and Mashkoor Ahmad. “Minorities and Poverty: Why some minorities are more poor than others?” Journal of Social Inclusion Studies, 2015: 126-142.

Waghmore, Suryakant. Civility against Caste: Dalit politics and citizenship in western India. New Delhi: Sage, 2013.

Zeeshan Husain is an independent researcher working on society and politics in Uttar Pradesh.