This piece discusses the recent sexual harassment allegations against a popular political figure in Kolkata’s student-youth spaces of activism. Engaging with the political concerns which came up in the context of this event, Jigisha Bhattacharya addresses the gendered nature of Kolkata’s universities and activist cultures, while focusing particularly on Presidency University. Simultaneously, she explores the relations between the digital social media, institutional forms of redressal, and the struggle for gender equality and justice in the context of today’s India.

The worldwide #MeToo moment of 2017 did not touch Kolkata’s youth as scathingly as did its own #MeToo moment in April 2019. Before this, there had been many isolated instances of harassers being publicly called out, of which the allegations against several members of the youth theatre group MAD (Mad About Drama) demands special mention: multiple survivors as well as erstwhile participants of the group came out with their stories of being bullied and harassed. However, the two faces of Kolkata’s student/youth politics remained largely out of this loop – Presidency University and Jadavpur University. As multiple survivors from Presidency University spoke out this April on Facebook about their experiences of sexual harassment, many others soon followed suit. Many popular faces of Kolkata’s political youth have since then faced allegations of multiple episodes and types of harassment. Mainly outed on social media websites like Facebook, the allegations of their crimes varied from verbal abuse to bullying, gaslighting, manipulation, physical molestation, and rape. Here I should mention that the terminology repeatedly used in these testimonies is of “forced oral sex/forced intercourse.” However, I will adhere to the terminologies of molestation and rape, for sex cannot exist in a binary of ‘forced’ and ‘consensual’ – let me state in clear terms that sex without consent is a form of rape. This is precisely the ludicrous false binary on which the state’s legal paradigm effectively sanctions marital rape, and which spurs on the self-appointed moral vanguards of our society to unleash survivor-blaming.

To make my position as a stakeholder in this entire scenario clear: I write this piece as an alumna of Presidency University who has seen the absolute lack of gender-sensitivity on my hallowed campus; I write this piece as a part of the student-activist circles in Kolkata and in Delhi and someone who has experienced several forms of these harassments first-hand; I write this piece in solidarity with the movement that was started in Presidency by the present students who were so courageously fighting against all odds.

What happened in Presidency?

Even though there had been multiple narratives about students and/or activists in the popular “Presi-JU” circles that circulated widely on social media after #MeToo went viral, things never took as much of a definitive turn then. Brishti Sen Banerjee, a final year student in Presidency University, was the first to initiate the discussion anew earlier this year when she wrote about her harrowing experience of sexual harassment, making allegations against a popular face of student activism on the Presidency University campus, Ayan Chakraborty. Brishti’s account informs us with clarity and resilience how she was forced to perform oral sex, and later how intercourse was forced on her by Chakraborty. Even when she tried communicating with Chakraborty about the violation of her consent, Chakraborty was quick to brush it aside, thus trivializing Brishti’s allegations by claiming that her actions proved a lack of discomfort, and therefore acquiescence of the sexual act. While she considered making the incident public for almost a year, Brishti only took to social media when she heard of a similar experience of harassment faced by another woman peer of hers at the hands of Chakraborty. “I needed to put my narrative to the public domain to make individuals aware of the person in question and to encourage others to come out with their stories if they are afraid to do so,” her Facebook post read. Brishti thus clearly narrated that there was a pattern to Chakraborty’s exploits, and it was time to put an end to them. Soon a number of narratives variously resonant with hers were shared – all involving the same perpetrator.

Sparked by one social media narrative, many erstwhile and current students of Presidency (and later of Jadavpur University) soon broke their silence about the ‘culture of fear’ which has been dominating these seemingly elite campuses. While their experiences encompassed many degrees of harassment, all of their narratives underlined the hypocrisy perpetuated by the progressive student groups on campus. How is there such a predominant culture of fear in these seemingly progressive spaces? How is it that in the wake of this movement, many batches of students from Presidency voiced very similar experiences they have faced over the years? How is it that a gender sensitization body, which is (barring ideological necessities) a NAAC necessity for university accreditations, is so dysfunctional when an elected non-parliamentary progressive body is running the Presidency University Students’ Union (Council)?

The glorified and combined halos of merit and progressive politics which have surrounded the political dadas (honchos) in these campuses for decades have been nurtured by political organisations and platforms of all stripes, their varying levels of toxicity depending on their political power at the time. As the received stories would have it, the masculine nature of progressive-left political spheres even plagued women activists in the 70’s and 80’s in Kolkata. In the very different historical context of the present, the political resolve of these leaders has become dubious, but their masculinity has only gained strength. Now the dadas can speak the select rhetoric of feminism (sometimes, if the situation so demands), and keep propagating their toxic masculine hold over political spaces. Slowly, and especially over the last decade, the remnants of democracy died one-by-one in Presidency, and progressive political alliances aided this change. First the student bodies accepted the Lyngdoh Commission guidelines; after scattered protests, they gave in to the hitherto unprecedented rules making attendance compulsory; finally, they passed by majority vote the administrative decision to transform the Students’ Union to the Students’ Union Council (one must give credit to JU students for resisting this move on their own campus). No final nail was needed any more as the possibility of progressive politics at the university was obliterated by then. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to uphold the idea of a Presidency which once existed and is now dead – the point, rather, is to understand the productive political possibilities which could have existed but did not.

Special mention needs to be made of the atmosphere of ‘apolitics’ in Kolkata’s activist circles and specifically on the Presidency University campus. Up until this point in time, the only election held on the concerns of gender was for the Girls’ Common Room Secretary post. The harrowing stories of violence unleashed by the Students Federation of India (SFI) on female (and male) activists from alternative left organisations were common news on campus, as the student front of the then-leading political party was thoroughly backed during their 34-year-old state-sojourn. In the absence of right-wing forces like the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) or the Trinamool Chhatra Parishad (TMCP) on campus, the alternative left groups based their critique of the SFI on the recent memories of sexual assaults by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) in Singur, Nandigram, and other places – and rightly so. Yet as the memory of Tapasi Malik and Radharani Ari started fading from collective memory, these political organisations too sidelined their critiques except on the occasional (working) Women’s Day celebrations. The annual festival organized by the Students’ Union, and run by one of the campus’ progressive political platforms went ahead with their paid endorsement of Tata Nano – hinging on which the battle of Singur was fought. When one probes into the rationale behind current events, these seemingly disparate incidents make up a narrative of a slow but consistent decay in even the minuscule potential of progressive politics which a campus like Presidency seemed to inherit. Beyond the occasional issues like fees hikes or a TMCP attack, Presidency has not seen a political consolidation beyond its regular activities of solidarity demonstrations in decades now.

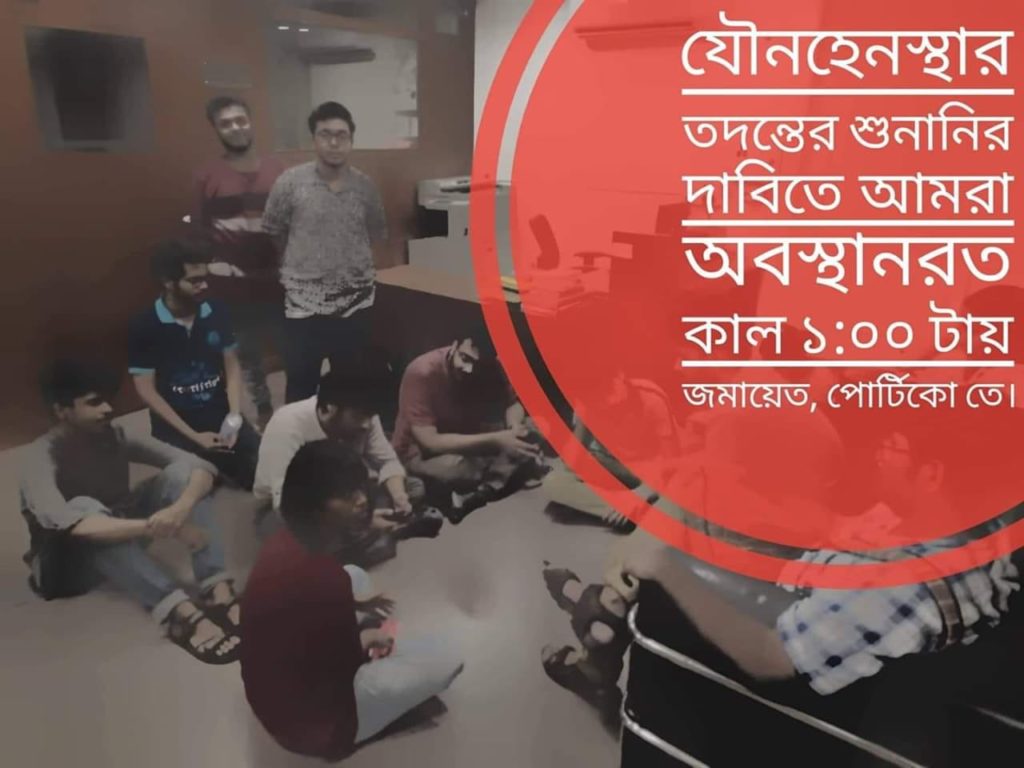

In the present scenario political parties, albeit with the help of informal but effective mechanisms, have only systematically shielded the miscreants, spread misinformation, and helped breed a toxic culture of fear and forced silence. These leaders seem to assume such power in the eyes of undergraduate and graduate students that a culture of silence continues to dominate the campus. And no one can possibly undermine the material manifestations of the power of slut-shaming, of survivor-blaming, of vitriolic casteism and classism. In a personal conversation with Brishti, she commented that the stories of the “misconduct” of certain leaders were common knowledge in these campus spaces, and the culture of fear is so overpowering that she too needed almost a year to pluck up the courage to publicly voice her story. A lot of friends advised her against this, citing the power-imbalance between her and the political collective to which the alleged perpetrator belonged. When she finally filed a complaint at the PUCASH (Presidency University Committee Against Sexual Harassment), all her efforts were time and again resisted by the authority, resulting in several protest demonstrations by the students. After repeated efforts the Presidency administration was finally ready to take cognizance of the case, yet their delay tactics continued, Brishti confirms. Manashi Sarkar, a peer of Brishti who has also been sexually harassed by Chakraborty, also expressed her discontent over the functioning of PUCASH in her social media posts. Following the protests, and citing concern over their safety, the Presidency administration, in a deeply insensitive move, issued a notice (via e-mail, after office hours) to the complainant (who is a final year student with impending semester exams, soon to leave campus) postponing the dates of hearing indefinitely. As per the latest available information, they have finally agreed to an alternative date of hearing following a mass sit-in demonstration by the students.

What about Kashmiri Pundits? What about Malda? What about?

It is important to engage with the popular and common responses which have emerged in political circles in the context of this movement, and more broadly with the trends of its methods. There are a couple of questions which need to be addressed here, all of which relate to the larger question of why this movement is important, if at all. Firstly, one of the most common and unquestionably counter-productive response has been, “How far would this naming and shaming take us?” More often than not, this question is raised publicly by our cis-male ‘comrades’ with an immediate addendum that the due course of law should be followed – thus denigrating the sharing of experiences as something purely anarchic or individualistic. Herein also lies the irony of alternative left-progressive politics, which keeps on packaging its politics in statist terms of legality, forgetting the reality of how the state usually deals with instances of sexual violence – by very often by assuming the role of the worst perpetrator itself. In the wake of #MeToo, it has become especially important to locate how young women from across sections have found a new medium of expression with their social media posts, comments, and shares. As proclaimed by many on social media platforms, these posts are useful as rapid circulation of ‘caution’ amongst potential future victims who more often than not belong in similar circles within reach. For a section of young women, social media platforms have provided an enabling space to share their experiences, and thereby a space for forging solidarities.

We have all engaged in various capacities with the experience-sharing norms that #MeToo (following African-American activist Tarana Burke) provided a space for – especially for today’s digitally equipped youth. However, the binary which has been created around #MeToo and its various moments, pitching it against the “older” trends of the gender rights discourse, obfuscates the fact that neither our society nor our politics function in terms of such binary divisions. As we are taken aback with the sudden surprise of #MeToo and its political strategy, we also recognize the difficulties that lie ahead for institutional mechanisms to begin addressing gender-justice on an everyday level – informally and structurally. The overall political picture – both institutional and colloquial – fails to systematically address women’s issues, offering us a gloomy vision of our future as proclaimed feminists. In such a scenario, not only has #MeToo been intrinsic to imagining a feminist-solidarity across class-caste sections because of the utilization of social media; this naming and shaming has also resulted in institutional action. Following several allegations, MJ Akbar was forced to step down recently, probes were initiated against several journalists on the national level, and the International Relations professor at Jadavpur University, Kanak Sarkar, was suspended on the basis of sexist remarks he made in a Facebook post.

As a student in JNU who was involved in the pro-GSCASH (Gender Sensitization Committee Against Sexual Harassment) movements, I have seen how the due course of law sanctioned by UGC-led Saksham Guidelines jeopardized an already established, democratic, more functional, and progressive GSCASH, by completely bulldozing student agitations in support of the existing GSCASH over the center’s dictates of a uniform Internal Complaints Committee (ICC). The movement also engendered legal and political battles over the Saksham vs. Vishakha guidelines which continue to inform the core of institutional mechanisms in our political circles. The crucial differences between the GSCASH and the ICC pertain to the methods of its constitution, the policies of redressal, and the manner in which the ICC body was imposed on a functional GSCASH. The JNU GSCASH was a body which was constructed through years of debate, development, and struggle in which the teachers and students alike were stakeholders. Unlike the ICC in which the election of its constituent members is optional, in the JNU GSCASH the students as well as the faculty and staff members were elected, ensuring that the manner of its constitution remained democratic. In contrast to the ICC – solely a complaint redressal cell – the JNU GSCASH was a body which functioned as both a redressal and sensitization cell. However, for campuses like Presidency, Jadavpur, and many other colleges and universities in Kolkata at large, a functioning GSCASH does not exist. In such a scenario, the instructions of the ICC itself prove useful in laying out a functional mechanism to tackle the rot at an institutional level. Beyond the solidarity building garnered by the sharing of experiences by many students, the recent incidents in Presidency University also cast a harsh light on the failure of the existing PUCASH as a redressal body. As Brishti herself pointed out, even when she did not endorse the politics of naming and shaming, she was bound to take recourse to the same, for the existing institutional mechanisms failed her, and indeed failed many like her before. That PUCASH has, on multiple occasions, threatened disciplinary action against (presumed false) complainants is common knowledge on campus. The PUCASH representative members are not public knowledge, which is compulsory under the present ICC guidelines. Nobody in the university seems to know how the students/teachers/legal representatives are selected to constitute the PUCASH, if at all. There have been multiple intimations on behalf of PUCASH where they have refused to reveal who the student representatives are, forcing the students to submit a formal note of dissent regarding the PUCASH procedures. Similarly, the PUCASH has intimated the post-facto inclusion of members in the committee to conduct inquiries on the allegations made by Brishti, Manashi and others. The survivors have been able to garner the support of the majority of the student body as they conducted general body meetings on campus between the existing political organisations, and other students. The student body to which Chakraborty belonged has suspended him over a social media post, and has extended its support to the survivors formally; the other majority student body (the SFI) has also extended full solidarity with the demands raised by the survivors. The survivors, along with politically dedicated students (many of whom are beyond the folds of the two dominant student organisations), have been relentlessly organizing protest-demonstrations in the face of their end-semester exams, have been demanding a complete overhaul of the PUCASH towards a more accessible and better sensitized campus.

What needs to be mentioned here is the role political groups on campus have played vis-a-vis the functioning of the PUCASH. Before this incident, no public statement was issued by any of the political organizations pointing out the malfunctioning of the existing PUCASH, or demanding changes in or accountability for its mechanisms. In my experience, the conversations around the GSCASH body at JNU, despite its limited capacity, did ensure certain forms of sensitization within the general student body. At the least, the students coming to the campus would know what constitutes sexual harassment and violence, and what does not. The absolute lack of any conversation regarding a CASH or its functionality ensured a culture of chest-thumping and fear-mongering on behalf of the political leaders, as the assumption was always that they would get away scot-free. Riding on the high horses of their class, caste, and gender privileges as they ruminated on politics, they demonstrated in their behaviour the very concerns they were rhetorically fighting against. Even in the larger discourse of activist spheres in Kolkata, the demands for a better sensitized campus have been insistently raised by only a few. It would not be a gross understatement to say there is a massive lack of redressal in incidents related to sexual harassment in Kolkata’s activist spheres. This is especially true because the Nirbhaya moment, that watershed moment in the national history of gender movements in India, never became as much of a public spectacle in Kolkata as it did in Delhi. The tumultuous movement of Hokkolorob which started off with the demand for the redressal of an incident of sexual harassment on the JU campus only achieved its peak political momentum when police brutality was involved. Undoubtedly, the Hokkolorob movement fought against the state-police-administration nexus which positioned itself against the student body. Yet, the very fact that the redressal of sexual harassment failed to gain adequate grounds in the movement speaks volumes about the gendered nature of the activist spheres. After all of their otherwise-justified demands like the removal of the Vice Chancellor were met, the primary demand of ensuring justice for the survivor, and the demands for establishing a GSCASH never reached fruition. Even though a few activists kept voicing the demand for a GSCASH in JU, all the student body was left with was a malfunctioning ICC in its place.

Are Molesters Beyond Political Parties?

Another recurrent set of responses raised in the context of this movement broadly allege that the entire movement is nothing but the result of long-standing personal grievances. Let me start by asking, what if it is about settling personal scores? As fashionable phrases like “the personal is the political” turned into oft-quoted axioms in activist rhetoric, reality demonstrated something completely different. In the absence of institutional mechanisms allowing for gender sensitization in these campuses, the political had surreptitiously turned personal. The student elections increasingly depended on individual charisma, on one-to-one networking, and less and less on political and ideological battles. In such murky terrain, it was evident that the gendered nature of the society would hardly ever be contested. The attempts at trivialization endorsed by these responses fail to recognize the political nature of what they deem “personal scores.” Years and years of personal experiences of abuse, bullying, harassment, violence, and trauma are what forms the core of feminist assertion, beyond all its different political strands. The fact that there can be such an attempt at trivialization, and that too along the lines endorsed by political leaders, only reveals the bankruptcy inherent in these groups’ functioning thus far.

Coupled with a continuous demand for ‘data’ to back up the allegations, such responses attack the heart of all remotely feminist conventions. The informal mechanisms through which lies, confusion, doubt, and false narratives are being propagated within campuses, as Brishti repeatedly mentions, are directly aided by responses like this. The demand for data on behalf of proclaimed radical/alternative left/progressive leaders is ironic at best, and reactionary at worst. The state is always demanding data whenever there are allegations of state-sponsored violence, while it simultaneously destroys all the evidence itself. At the same moment the state either does not allow the data to be revealed, or erases the evidence with utmost expertise, the discourse of the state dismisses all experiential and oral narratives as redundant – from Kunan-Poshpora, to Thangjam Manorama, to Tapasi Malik. In a very different context, within the murky sexualized and gendered public sphere which the Indian neoliberal economy has produced, the possibility of securing and establishing data and proof becomes increasingly arduous. For the all-pervasive nature of sexual harassment evades our common understanding of furnishing ‘data.’ If one were to furnish proof for every time a woman is catcalled, every time a woman receives lewd comments, every time a woman is touched inappropriately, it would require a change in our very understanding of what ‘data’ is. At the same time, the consistent need to furnish data also inspires a policing state, and a policing state of mind – we are always capturing photos, recording calls, videotaping our surroundings, so that we are able to secure ‘evidence’ worth furnishing. One side of the popular demands during Hokkolorob demanded the installation of CCTV cameras to solve problems of sexual harassment, whereas a popular political leader voiced the need of installing streetlights in Kolkata to ensure an end to sexual harassment while addressing the Hokkolorob crowd. CCTV camera installation ensures a mechanism of surveillance, propagating the idea that one is always potentially a victim, while effectively reducing the possibilities of everyday resistance. We feel safe that there is a CCTV installed. We feel safe knowing that someone is watching over us – even if it is only a machine monitoring us, and while in reality all these surveillance mechanisms have proved to be redundant in resisting possible acts of crime. Notwithstanding the need to guarantee women’s safety, the demand to increase security has voluntarily/ involuntarily supported surveillance at the same moment that the imperative of producing clear evidence of possible crimes is always put on the complainants – socially and institutionally. The demand for data to substantiate allegations, as opposed to the ‘personal grievances’ of experiential narratives, ends up as an extremely reactionary, staunchly vitriolic, and utterly counter-productive political position.

Let me now address another recurring response encountered in the otherwise barren ground of political responses in the wake of this moment in Kolkata political circles. This set of responses, circulating in everyday discussions as well as social media posts by individuals and political organisations alike, raised the point that “molesters are beyond political parties.” Needless to say, these critiques are coming from the members, associates, and cohorts of the political groups to which the alleged members belong(ed), and sometimes from other student groups as well. Now, it is undoubtedly true that these elite institutions too are a part of the society, and therefore all the societal vices would be present within the individuals who flock to these campuses. However, what needs pointing out, is how this opportune moment of allegations of sexual harassment is being seized to situate Presidency University as a part of the society. The irony is, for as long as public memory serves us, Presidency has been put on a pedestal as a liberated space, as a “bulletproof idea.” In the progressive political circles of Kolkata, the campus spaces of Presidency and Jadavpur have gained an alarming amount of political clout over other educational spaces. Even a cursory look at the propaganda posters within these campus spaces, or the circulation of political posts on social media will confirm how students boast of these campuses. Some of the common slogans which have dominated the political rhetoric in the Presi-Ju circles are, “Presidency shikkha dey aghat jodi nemei ashe palta aghat phiriye dao” (Presidency teaches you to resist in the face of attacks), “Ideas are bullet-proof. And Presidency is an idea”, and “Lathir mukhe gaaner sur, dekhiye dilo Jadavpur” (To sing in the face of blows, this is what Jadavpur shows).

How Progressive is Progressive Students Politics in Kolkata?

The understanding that Presidency and Jadavpur are spaces situated within society was side-lined into oblivion by these popular political assertions. Whenever there arose the situation of contesting mainstream political parties, that contestation would chiefly consist of the assertion that there is no presence of the student fronts of either the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or of All-Indi Trinamool Congress (TMC) within these campus spaces. Even though the organisations would keep the rhetoric of accepting/reaching out to the ‘masses’ beyond the boundaries of the campus life, it would always be a relationship of patronage, superiority, and oblivion. Not surprisingly therefore, such an outlook continued to propagate as deep a divide between the insider and the outsider as the question of what it meant to contest. Whereas it should be welcomed that Presidency students are (finally) accepting responsibility as societal beings, there has to be some reflection on the motive behind grabbing this precise moment to do so, i.e. after allegations of sexual harassment against their members. The intention of such a move has to be questioned too, especially as the usual response to complaints of harassment within or against these organisations is to brush it aside, sweep it under the carpet, or at most to suspend the alleged members. In the absence of any concrete mechanisms or means of sensitization within these campus and activist spaces, such decisions of suspensions/expulsions chiefly translates into political organisations disclaiming responsibility of the whole matter. The sudden claim that all the societal vices are also present on progressive campus spaces performs a similar function: that of absolving the organisations of their share of responsibility as spaces which claim to nurture political activism. Despite tall tales of progressive political vibrancy, the reality remains that these elite campuses have served as the breeding grounds of patriarchal vices that they otherwise vow to dismantle.

Let us turn to how gender is formally placed within most of these political organisations. Women are in charge of the gender forums of these political outfits. Now at a cursory glance, this seems hardly problematic politically, because our common sense clubbed with our feminist ideas tell us women should and would represent their issues. The crucial double bind which exists here is how such gender-forums are placed structurally within the political activities of these student groups. As the left has traditionally seen anything beyond the economic/rights discourse as merely cultural, merely social, it has denigrated gender forums/organisations as something unworthy of serious political engagement, both internally as well as within the larger political culture. These sister-outfits that work on gender-related issues are assigned primarily to the women-comrades and function as work-bases one or two levels below the “core” organizational work. The functioning of the gender forum never becomes a part of the organisation’s core political duties. As our older women comrades screamed their lungs out about developing the crucial presence of gender in all our political activities (I’m not even including the category of caste here which leads to severe bullying in and outside youth spaces), what came out of it were gender forums as a space assigned for women. Most of these gender forums only dealt with issues of direct violence, or became an experience-sharing space for women, were never included in the everyday political functioning of the so-called “core” outfits. As the perception goes, the gender forums were not outfits to be dominated by women because women do understand gender better experientially, but as a forum to be managed by women so that the gender box of the organisation can be ticked off.

It is not an understatement to say that none of the youth political organisations seem to have a functional mechanism of gender sensitization within the organisational or activist spheres, as evident from the numerous allegations over time. There was hardly a need felt to organize gender workshops internally within the organizations, hardly a need ever felt to form redressal/sensitization committees regarding the issue of gender even when multiple complaints were received by the organisation in question. In the everyday functioning of these groups, there are fixed roles that women are assigned, and fixed performative structures for these roles. Women activists would carry out the cursory duties at political meetings, replicating how women have traditionally done so within their assigned spaces in the household. Almost in the same manner that a female student is believed to be a more meticulous note-taker than a male student, in a direct extension of their idealized classroom lives, these women would ferociously write down the minutes of political meetings as the dadas would continue to speak for hours. Especially at a time when the conceptual categories of mansplaining and manspreading were not a part of the political rhetoric of feminism, any attempt at rebuttal or refusal of their politics by women would be brushed aside and argued down. On a limited number of occasions – almost always on gender-related issues like (working) Women’s Day, for example — women activists would perform, but only after being groomed by the dadas. Women would hardly ever make the cut to the higher rungs of the core committee, and if they did, scintillating stories about their close sexual ties with the popular dadas would be the talk of the town. And when anything related to gender would come up in the discussions, the male comrades would deem it fit to take long smoke breaks outside as the conversation went on, claiming, “You people handle gender no! (We have better things to do.)” I see these not as one-off incidents but as symptomatic of the larger culture of harassment which has been promoted within and by these student outfits. Even the veteran leader Krishna Bandyopadhyay, in a recent discussion on the revolutionary women of Naxalbari, had to voice the need for women to occupy and transform the leadership of the political spaces of our times.

Now, how does it happen that a gender forum – which essentially emerged out of century-old feminist movement – falls into such a domesticated, conventionally feminized space? And if it is indeed so, how do we engage with it as women who identify with the left-leaning political outfits, do not want to disown the history of its struggles completely, and yet strive to make a space conducive to women’s safe and healthy lives? In contemporary times, it has become increasingly difficult to initiate a conversation around the concerns of rights and choice, especially with regard to gender. These student groups have, on the one hand, played along successfully in foregrounding a dubious politics of an illusory choice, where the average (and therefore “apolitical”) woman student on campus is urged to join the women’s cause because they must stand up. On the other hand, these forums systematically contribute to the shrinking of space for a deeper political engagement with issues related to gender, as their members unleash the same kinds of harassment within these activist spaces as those which exist outside its peripheries.

It is hardly surprising, then, that there is an immense lack of proper measures for sensitization and politicization within these outfits in general, or after allegations are brought against their members in particular. Post facto suspension or expulsion of the alleged members from the organization, or a complete indifference to the allegations are, respectively, the formal and informal way in which the activist spheres usually respond. As the dominant trends of responses demonstrate, the intention still is to reject all responsibility on the part of the organisations themselves. How do we then engage politically with such a pervasive atmosphere of fear which is spread systemically, and for which hardly any redressal mechanism exists? Having been a part of the progressive left student circles in Kolkata myself, there are certain recurrent trends that the student outfits propagate systematically, irrespective of their minute internal political differences. Barring a handful, none of the political outfits (organisations and platforms alike) which operate in these university spaces (and I am still speaking of these elite universities) have sensitization committees. This is not to say that having formal committees within political organisations is going to solve all their problems. Especially if one imagines the political organisations/activist spheres to be spaces of transformation, there is little space left to imagine a statist paradigm of redressal committees. However, in the present scenario, we must take a step back and truly reflect on the possible mechanisms of dealing with the rampant atmosphere of toxicity, harassment, and the resultant vulnerabilities. Having sensitization committees within the fold of the political organisations could actually begin a conversation where a resolution to these problems can be imagined. We could begin with having sensitization committees that will conduct workshops and intervene in its semi-autonomous capacity within the gendered nature of the organisations. This measure should not be to kill spontaneity at the cost of surveillance, but to make sure that activist spaces are a spontaneous space for all – irrespective of their gender. This measure should be towards initiating real conversations around gender, and making real interventions beyond the rhetorical level.

In circumstances marked by an extreme lack of gender sensitivity, clubbed with malfunctioning institutional mechanisms, the student protestors in Presidency University have few options left. And yet, they have been remarkably vocal in arguing their case for a better and just CASH-body which, as they imagine it, would not only act as a punitive body, but will ensure an overall atmosphere of gender sensitivity. While commenting on the present situation regarding the movement, Brishti says, “There can be no gender-sensitized atmosphere in Presidency without a CASH overhaul. There have to be elected representatives in the CASH. Even if by sheer miracle I am able to receive justice, that would be a one-off incident. The real goal is to ensure a safe and sensitized campus for all.” Sukanya Bhattacharya, a fellow undergraduate student in Presidency and a protester, says that, “It’s not yet a defining moment for Kolkata if it only remains within our immediate elite universities of Presidency-JU. Kolkata at large still lacks a moment like this. A CASH is still a known concept in our political circles, but, if we just venture out of these two, three places, there is no such machinery in other educational spaces. As our friends repeatedly keep informing us, the student-politics beyond the Presi-JU campuses has a far more violent and precarious face.” She further adds that this moment has indeed been important in the context of these so-called progressive campuses because it was able to unveil in some capacity the inherent hypocrisy of these activist spheres as many woman called out people in power. She echoes Brishti in her reflection, saying that the aim really is to ensure a safe and just space for women and minorities across class and caste barriers, both within and beyond these campuses. As I write, many including Brishti, Manashi, and Sukanya are long-past their days of hunger strikes and agitations, and are waiting for a final hearing to take place.

[Jigisha Bhattacharya has been active in student politics in Kolkata and Delhi. Beyond her life in academia, she engages with issues of gender and education politically, and tries to imagine a better future. All accounts have been used with permission. The title alludes to Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Cover photo: Samir Jana/Hindustan Times. All other photos: From Facebook posts sourced by Jigisha]