A hundred years to this day, the British massacred unarmed people in Jalianwalla Bagh, in undivided Punjab. From today’s critical juncture, Nilanjan Dutta looks back at the significance of 1919 for an articulation of civil liberties.

One hundred years ago, India stood at a critical juncture. The end of the First World War, with its accompanying social and political shake-ups, the prospects of political change looming with the introduction of the Montagu-Chelmsford scheme in 1919, mass unrest, as well as severe state repression epitomised by the Rowlatt Bills, military rule in Punjab and the Jalianwalla Bagh massacre – all contributed to the building up of a high tension. At the same time, the civil society was becoming more and more aware of its rights, and more and more eager to claim them. Indeed, the previous year (1918) saw the formation of the Civil Rights Committees in Madras and Bengal.

Even before this situation became full-blown, Pandit Jagat Narain, in his welcome address to the 31st session of the Congress at Lucknow on 26 December 1916, had observed:

The last decade has witnessed the birth of a new nationalism in India. The efforts of the other generation to awaken the consciousness of the people have produced their inevitable result. A new generation has arisen with new thoughts and new ideas, impatient of its dependent position and claiming its rights as free citizens of the British Empire.

The ability to conceive themselves not as subjects of a colony but as free citizens of the empire was a necessary precondition for the members of the Indian civil society to claim their rights. The bearers of this thought were, of course, constrained by their ‘elite’ character, numerical minority and propensity to compromise with the colonial interests because of professional/business compulsions. However, it should be noted that a large number of members of this section did not have a necessarily antagonistic relationship with the masses. They were socially mobile and flexible in their outlook, and their talk about civil liberties had a responsive audience as it was compatible with the contemporary social demands.

The libertarian ideals of the “new generation of nationalists” were rooted in the emerging class structure and the popular mood in India, as well as the tumultuous global situation, marked by the Russian Revolution and the Irish struggle for self-determination. The War period was a time of growth for the bourgeoisie in India. With their growing economic and social influence, they began to make their presence felt in the nationalist movement, both physically and ideologically. But if they were not willing to go far to press for civil rights, the middle classes were. The reasons for their discontent were explained vividly by lawyer Alfred Nundy in 1919 in his book, The Present Situation with Special Reference to the Punjab Disturbances. Nandy, a former public prosecutor of Rawalpindi, was the first to conduct a detailed independent inquiry into the Jalianwalla Bagh massacre of 13 April 1919. The book was a compilation of his inquiry reports, appearing in 15 installments between 28 April and 5 July in Leader, a Moderate daily published from Allahabad. First published on 5 August 1919, it became highly sought after, and a second edition appeared on 20 November the same year. Though the lawyer’s faith in the “good effects” of British rule was apparent, he was one of the new rights-conscious citizens of India and had a strong power of observation. He could accurately express the sentiments of the members of his class, in a language that is strikingly modern. If we abstract it from the colonial context, we would find it highly congruous with our contemporary discourse.

As a result of the war, famine prices are ruling as regards articles of food, of clothing and other necessaries of life…. While crores of rupees have been appropriated for the extension of the railways, which it is supposed, and perhaps wrongly, will mainly serve a military purpose, even a paltry sum is not available for free and compulsory education, on which, good many believe, depends the advancement of the country. Nor, in spite of profuse professions and promises, is any serious effort being made to promote the industrial development of the country, which all are agreed would be conductive to its material prosperity; and the irritation is natural in view of the prospect of India becoming the dumping ground for the goods of the rest of the world in return for its raw materials taken at a low price.

The public discontent had spread beyond the middle classes. The period of 1918-20 was also a time of rapid growth for the trade union movement in India, and of the entry of the working class into national-level politics. The working class was not only staging economic strikes but also political ones, as it did in protests against the Rowlatt Bills in Bombay and other industrial zones. The participation of the peasantry, especially its poorer sections, in ‘modern’ politics had been held up until this period for various reasons. In the first Non-cooperation Movement and No-tax Campaign of 1919, their presence was felt across the country, and their organisations – the Kisan Sabhas- proliferated within a short period.

The ‘Declaration of Rights’

All these classes and sections constituted the emerging civil society in India, with a broadening social base, and its members constructing for themselves a ‘citizenhood’ in place of ‘subjecthood’. “The stage was set,” as A.R. Desai remarks, “for a nationalist movement with a mass basis.” The common aspirations of the people were reflected in the resolution on ‘Declaration of Rights’, adopted at the special session of the Congress held at Bombay in September-October 1918 and endorsed by the All India Muslim League. The Declaration was the first comprehensive document produced by the Indian nationalist movement on the issue of civil liberties. It envisaged a formal contract between the colonial state and the people of the colony, allowing the Government of India to have “undivided administrative authority on matters directly concerning peace, tranquility and defence of the country”, subject to the inclusion of “the rights of the people of India as British Citizens” in a statute to be passed by Parliament. The statute should state:

That all Indian subjects of His Majesty and all the subjects naturalized or resident in India are equal before the law, and there shall be no penal or administrative law in force in the country, whether substantive or provisional, of a discriminative nature; that no Indian subject of His Majesty shall be liable to suffer in liberty, life, property, or freedom of speech or in the right of association, or in respect of writing except under a sentence by an ordinary court of justice and as a result of a lawful and open trial; that every Indian subject shall be entitled to bear arms subject to the purchase of a licence as in Great Britain, and that the right shall not be taken away, save by a sentence of an ordinary court of justice; that the press shall be free and that no licence nor security shall be demanded on the registration of a press or a newspaper; and that corporal punishment shall not be inflicted on any Indian save under conditions applying equally to all other British subjects.

With a view to incorporating it in the new Constitution of India to be introduced under the Montagu-Chelmsford scheme, this charter was submitted to the British Parliament. The move, however, yielded little response from the latter. On the other hand, in the opinion of activist journalist B.G. Horniman, the colonial government’s answer to the demands expressed in the Declaration of Rights was the introduction of the Rowlatt Bills. The Rowlatt Bills sought to make permanent the repressive provisions contained in the Defence of India Act of 1915, which had outlived its term. The Bills were explained succinctly in a contemporary popular saying: “Na dahil, na vakil, na appeal” (No defence, no counsel, no appeal).

The movement against the Rowlatt Bills was a landmark in the history of civil resistance in India. Earlier, protests against repressive measures took the form of resolutions, petitions, meetings, etc. But, for the first time, a country-wide mass agitation was launched demanding the withdrawal of the Rowlatt Bills. The movement, known as the ‘Rowlatt Satyagraha’, was the most destabilising experience for the Raj since the Revolt of 1857. Three years later, leftist leaders M.N. Roy and Surendra Nath Kar reflected on these events:

In fact, the Rowlatt Bills were formulated only to continue the state of affairs obtained under the Defence of India Act. But the latter, enforced with an iron hand in the years immediately preceding, did not provoke any serious popular opposition. This goes to show that a new force had come into being around 1919. It was the awakening of mass energy, brought about by economic exploitation intensified during and immediately after the war.

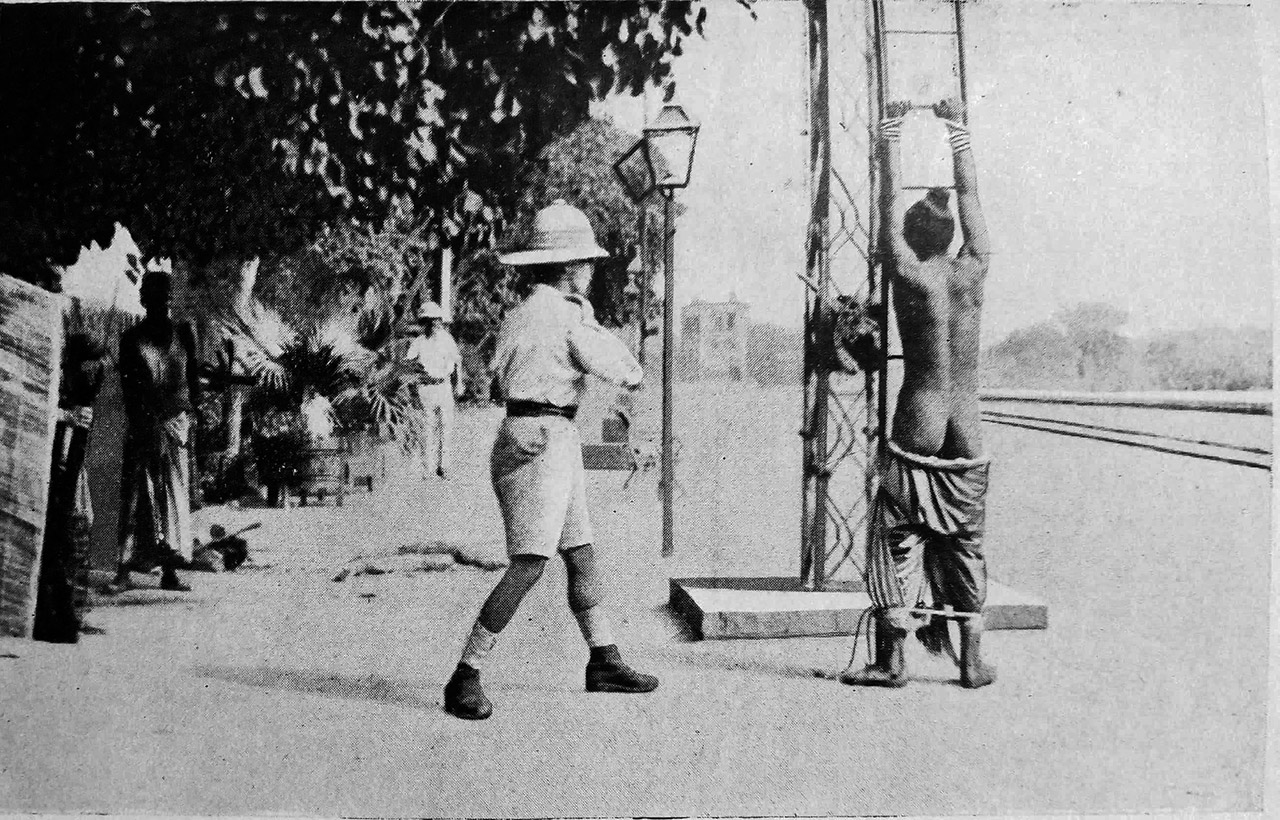

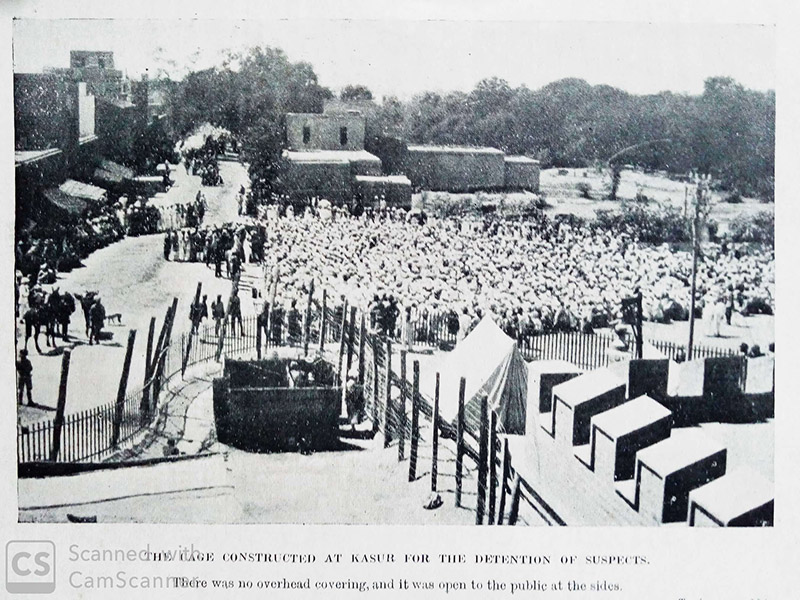

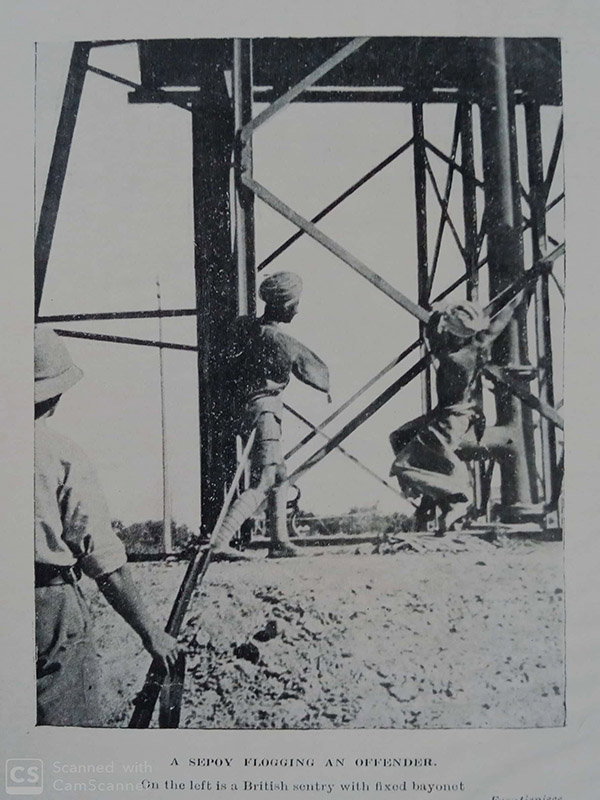

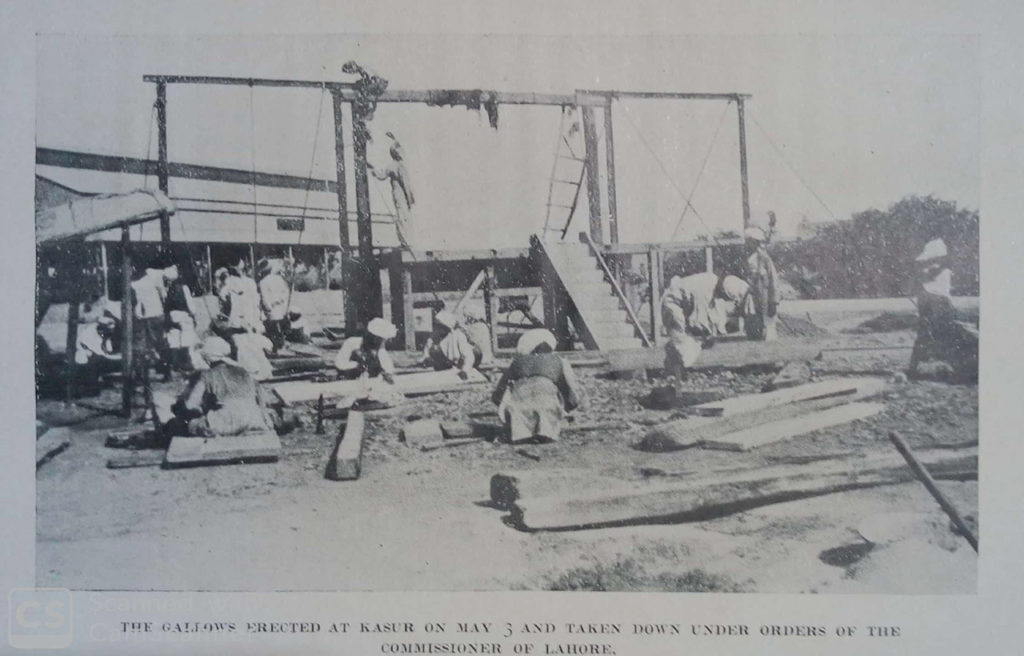

The imposition of martial law in Punjab and an all-out assault on civil liberties, including public floggings and many other forms of degrading treatment, characterised the colonial state’s policy towards this “awakening of mass energy”, culminating in the Jalianwalla Bagh massacre. The repression evoked strong condemnation from the Indian liberal intelligentsia. Well-known instances are the renunciation of Knighthood by poet Rabindranath Tagore and the resignation of Sir Sankara Nair from the Governor General’s Executive Council protesting against the Punjab firing. The Congress, expressing lack of trust in the official probe on the incident, appointed a parallel enquiry committee. Late Marxist intellectual Gopal Haldar has reminisced in his memoir:

The day Rowlatt Act was passed – it was observed as a protest day in Calcutta – there were no trams and cars in the streets (buses had not yet been introduced). A public meeting was held at the Monument Maidan – probably the first meeting to be held there… it was a seething multitude.

Alfred Nundy observed that the protests also brought the religious communities in India on a common platform. “Perhaps the severest blow” to the Raj, he said, was that the two communities– the Hindus and the Muslims were not only “fraternalising” in political matters, but were also “exchanging social amenities” and even “relaxing their religious prejudices for political ends”. Indian Christians, too, sympathised with the cause and they organised a dinner in honour of Sir Sankara Nair after his resignation.

Thus, the events of 1919 challenged two fundamental assumptions of the Raj: first, that it was not possible for a real mass movement to rise against the state in the colony; and second, that the religious divide in India was insurmountable. A situation that would prove either of these assumptions to be false had always been a nightmare for the colonial rulers. For the civil society in the colony, though, such a situation could act as a rejuvenator. And it did.

The Rights of Citizens

In June 1919, S. Satyamurthy, a young Congressman from Madras who later became a martyr in judicial custody in 1943, wrote a book titled The Rights of Citizens. The book found a wide readership in India and abroad (it was included, along with the Congress report on Jalianwalla Bagh, in Lenin’s personal reading list on India).

Satyamurthy not only provided a critique of the British government’s attitude towards civil liberties, but also a positive foundation on which the struggle for these rights could be constructed. He classified and defined the “rights of citizens” in six categories – “the right to personal freedom, freedom of judicial trial, freedom of the press, the rights of public meeting, freedom to bear arms, and to serve in the army and the navy, and freedom to enter the public services” – defending each of these and examining how far these were available in India, liberally citing the opinions of British legal experts as well as Indian public figures.

The author first gave a negative definition of the right to personal freedom as the right against unlawful arrest, detention without trial, or “other physical coercions not having legal jurisdiction”. Then, following British jurist A.V. Dicey’s Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1885), he suggested a set of positive rights which could enable a citizen to seek remedies for the violation of this right. These were: 1) the right of prosecution against the person responsible for illegal arrest; and 2) the right to a writ of Habeas Corpus.

While dealing with the freedom of judicial trial, Satyamurthy cited Ambica Charan Mazumdar’s speech at the Lucknow Congress of 1916. The latter said it was the administration of justice, more than anything else, which had “laid broad and deep the foundations of British Rule in India”. And “anything which tended to undermine that foundation is therefore fraught with danger to the superstructure”, he warned.

For freedom of the Press to be fully operative in India, the Indian Press Act of 1910 should be repealed, said Satyamurthy. The Act was framed on the basis of the Press and Registration of Books Act, 1867, with clauses providing for declaration security and penalty of additional security or forfeiture in case of sedition charges.

What Satyamurthy called ‘the right of public meeting’ was essentially the right to assembly. In India, though in theory the rules governing the use of force to disperse ‘unlawful assemblies’ were largely similar to those in Britain, incidents of shooting on demonstrators in Calcutta, Madras, Ahmedabad, Amritsar, Lahore, Delhi and other places during the 1919 agitations showed that these rules were often violated. The remedy, Satyamurthy said, lay as much with the government as with the people. While the former must take “scrupulous care” to see that the “well-known limitations on the exercise of such extraordinary powers” were not transgressed by subordinate officials, the latter must “bring all exercises of arbitrary powers by the police or by the executive before the courts of the law in the land, who may be trusted to uphold the rights of the subjects”. Thus, almost presciently, he emphasised the role of public-interest litigations in the protection of civil liberties, which has become a well-established tradition in post-Independence India.

Satyamurthy was in no way bound by a mere legalistic framework and attempted to demystify law itself. In fact, he showed that repressive laws not only curtailed civil liberties, but crippled the very consciousness of liberty among the members of the civil society.

Accustomed as we are to live under laws and regulations restricting our freedom in various ways, we have, especially in India, come to hold the belief that these laws are part of the scheme of nature and that we have nothing to do with them, but to obey them…. Thanks, however, to the political awakening in the country, a different attitude is beginning to be assumed towards these man-made laws.

The “different attitude” was manifested in Resolution No. XVI adopted at the 34th session of the Congress at Amritsar in December 1919. It sought to add an additional safeguard clause to the statute proposed in the Declaration of Rights. The clause said that all laws, ordinances and regulations now or hereafter in existence, that were in any way inconsistent with the provisions of this statute, “shall be void and of no validity whatever.”

In other words, laws must be made compatible with people’s rights; rights cannot be tailored to fit the laws. This was the quintessential demand that the emerging Indian civil liberties movement raised in 1919, the year of “the awakening of mass energy” in India. A century has passed, but its relevance has only increased.

Cover Image: Tied to Ladder – picture of an Indian tied to a ladder at Kasur railway station being flogged.

All images including cover image used in the article taken from Amritsar and our duty to India by B.G. Horniman.