The Global Climate Risk Index 2019 ranks India as the 14th most vulnerable country to the impacts of climate change. According to a recent government study, every year in India around 5,600 people die as a result of extreme weather events. A country faced with impending climate catastrophe, instead of taking emergency damage control measures is going ahead with the rapid expansion of Petroleum Industry which created the climate crisis in the first place. A discussion by Siddhartha Dasgupta.

Devastating new reports on climate crisis

A shocking new report found that at least a third of the Himalayan ice cap will melt by the end of this century due to anthropogenic climate change, even if the world’s most ambitious environmental reforms are implemented. The report, released on February 11 by The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment, is the culmination of 6 years of work by over 200 scientists, with an additional 125 experts peer-reviewing their work. The report warns that rising temperatures in the Himalayas could lead to mass population displacements as well as catastrophic food and water scarcity.

The Himalayan glaciers are a vital water source for the 250 million people who live in the Hindu Kush, a part of the Himalayas which runs from Afghanistan to Burma. This is the home to the third largest mass of ice in the world, after Antarctica and the Arctic, and is often referred to as “The Third Pole”. Over 1.5 billion people depend on the rivers that flow from this region, including huge swathes of the Indian subcontinent. Experts have said that at the current rate of warming, the planet could potentially lose all its glaciers by 2100.

Another alarming new report has found that more than 40% of insect species around the world may become extinct in the next few decades. Although the authors conclude that industrialized agriculture is the main culprit, they also assign blame to climate change. They cite rising temperatures that have led to sudden decreases in insect population in places like Puerto Rico, where nearly all the ground rainforest insects have disappeared in just 35 years. This devastating news should be understood in conjunction with the finding that 2018 was the fourth-warmest year on record. The last five years have been the five warmest years since reliable measurements began more than a century and a half ago.

Human-kind is driving the Earth towards a catastrophe unlike anything that we’ve ever seen. If all countries managed to achieve all their climate commitments, the earth will still get 3°C warmer by 2100, twice the 1.5°C limit agreed upon in the Paris Agreement of 2015, according to a report released by Climate Action Tracker in December 2018.

From the falling biodiversity in the Amazon, to the loss of ice up in the Alaskan Range, to accelerating rise of sea levels, to the certain death of the Great Barrier Reef, the alarm bells are ringing all around us.

How is India’s climate and environment doing?

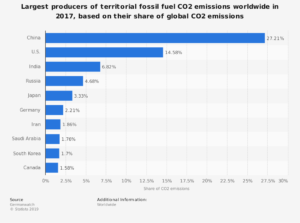

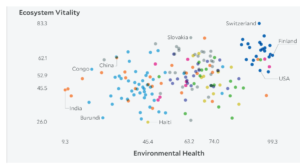

India is one of the worst-affected nations in the world, while also being one of the biggest emitters of carbon. A biennial report by Yale and Columbia University along with the World Economic Forum released in 2018 ranked India 180th out of as many nations in the environmental health category. India ranked 178 out of 180 as far as air quality was concerned.

According to the Global Climate Risk Index 2019, India is the country 14th most vulnerable to impacts of climate change; each year in India around 5,600 people die as a result of extreme weather events, according to a recent government study. These are the official numbers and they do not count the huge number of unreported deaths. A 2018 World Bank report titled “South Asia’s Hotspots : Impacts of Temperature and Precipitation Changes on Living Standards” estimates that around 44.8% of India’s current population lives in locations that could become moderate or severe climate hotspots by 2050 if efforts to fight climate change continue as planned. India will increasingly witness the irregular trends of extreme rainfall leading to floods in some regions, and weaker monsoons leading to droughts, according to a report by Climate Trends. In a country where 56% of the farms are unirrigated, this means serious threats to food security for the entire nation.

An 1°C rise in temperature reduces farmers’ kharif (winter) incomes by 6.2% and rabi (monsoon) by 6% in unirrigated districts, according to an IndiaSpend report. For every 100 mm drop in average rainfall, farmer incomes fall 15% during the kharif season and 7% during the rabi season. The 2016 World Bank report predicts that by 2030, the income of the bottom 40% of people will reduce in comparison to scenarios without climate change. Economic losses from the 2018 floods in the Indian state of Kerala alone exceeded damage from all flooding in India in 2017, and reduced real GDP growth in the state by 1%.

We must also note that such risks and casualties are not going to be evenly distributed. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that it will “disproportionately affect disadvantaged and vulnerable populations through food insecurity, higher food prices, income losses, lost livelihood opportunities, adverse health impacts, and population displacements.” A Climate Trends report looks into the relations between climate crisis and poverty. “Without intervention, India will be a main location of extreme poverty by 2030,” the report says.

What steps has the Indian Government taken and how far have we progressed?

As a signatory to the Paris Climate Accord and other such international agreements on climate change, the Indian government had announced a “special focus on renewable energy” and promised legislative and fiscal measures towards the same. Accordingly, a Council on Climate Change was set up, headed by the Prime Minister. The National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) was announced, and the National Adaptation Fund on Climate Change (NAFCC) was set up. The erstwhile “Ministry of Environment and Forests” (MoEF) was renamed to “MoEF & Climate Change”. Several missions were announced under this Fund, such as National Solar Mission, National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture, Mission for the Himalayan Ecosystem, etc. A State Action Plan on Climate Change were also announced to take the agenda to the state level. However, a mere Rs 10 lakh was given to each state to set up their respective nodal agencies.

Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a method of quantifying and numerically marking the environmental performance of a state’s policies. A low score indicates poor performance.

The Government of India allocated a mere 350 crore rupees ($52.8 million) to the Climate Change Fund, intended to cover expenses for two financial years 2015-16 and 2016-17 — a sum which environmental experts say is woefully inadequate given the size of the country and the challenges it faces. After cyclone Aila (2009), which affected 100,000 people, the Indian part of the Sunderbans was allocated 500 crore rupees ($75 million), a sum that pales in comparison to the damage done. In the last couple of budgets, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley maintained total silence on environment and climate change. According to the MoEF’s annual report of 2017-18, only Rs 263.31 crore has been sanctioned for projects out of the initial outlay of 350 crores.

A Climate Change Action Program was also approved by the Modi Government in 2014, with a budget of 290 Crore rupees for five years. Coupled with the allocation to the Climate Change Fund, the total amount of money allocated over the last five years by the Modi government to study and combat climate change amounts to Rs 640 crores. We will come back to this figure once again in the report.

A ‘Green’ Prime Minister rolls out the Red Carpet for Petroleum

The recent visit of Saudi prince Mohammad Bin Salman (MBS) right after the Pulwama incident has been criticised across sections of the media. Many watched in disbelief as red carpets were rolled out for a dictator, who only the previous day announced major economic deals with Pakistan – accused by the GoI of being behind the Pulwama incident.

But ever since coming to power, the Prince – known for his ruthless ambition and dictatorial agenda – made headlines after torturing domestic dissidents and upping the illegal Saudi invasion of Yemen. These problems were exacerbated when the Prince was accused, even by American intelligence agencies, of executing the brutal murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi who worked with the Washington Post. A drugged Khashoggi was cut up into pieces using a chainsaw by a group of Saudi hitmen in plainclothes inside the Saudi embassy in Istanbul. The group was allegedly directly recruited by MBS himself. The G20 Summit where Modi and MBS made their business deals took place within a month of Khashoggi’s murder. Business, however, went on as usual at the summit. The two leaders talked about setting up “a mechanism at the leadership level to scale up the oil-rich kingdom’s investments in energy, infrastructure and defence sectors in India”, as reported by MoneyControl.

What was relatively under-reported about this particular visit of the Saudi prince was the business deals he signed with Narendra Modi. Much was made of the $20 billion investment deal that was signed with Pakistan, not much has been said about Saudi investments in India.

Saudi Arabia is India’s 4th largest trade partner and a major source of our energy. We import around 19 per cent of our crude oil requirements and 32% of our LPG requirements from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

ARAMCO

Earlier in April 2018, Saudi King-owned petroleum company ARAMCO, one of the largest in the world and the main historical axis of the US-Saudi relations signed a deal with a consortium of Indian refiners to build a $44 billion refinery and petrochemical project with the Ratnagiri Refinery and Petro-Chemical Project Ltd. in Maharashtra. The huge project was touted as a “game-changer” for both parties – offering India steady fuel supplies and meeting Saudi Arabia’s need to secure regular buyers for its oil. Jobs were promised and “development” was guaranteed for everyone. But the proposed refinery, ever since its announcement, has been opposed by local farmer’s groups, environmental groups, NGOs as well as various political parties including the Shiv Sena. The project would jeopardise not just the interest of the farmers, but also destroy the ecology of Ratnagiri district in the bio-sensitive Konkan coastal region.

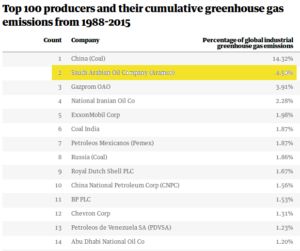

According to a 2017 report released by the Carbon Disclosure Project, ARAMCO is the second largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (the chief factor behind the present global climate catastrophe) in the world, second only to the Chinese coal mining industry. ARAMCO was among the 100 companies that account for 71% of the total global emissions, according to the report. In February 2017, Forbes magazine announced “The markets are awaiting what is expected to be the biggest public offering in history. An IPO so big it will likely make any Silicon Valley unicorn look like a blip in the market.” Saudi-owned ARAMCO was going public, valued at $2 trillion, making it the largest IPO ever, even bigger than Exxon Mobil or Apple. Public listing of ARAMCO is linked to the fact that faced with global political movements on the issue of climate change, the Saudi regime has decided to diversify their economy out of petroleum in a phased manner. Global confidence on the stability of the petroleum market is becoming shaky, the Saudi state wants to outsource its risk in case the oil market takes a hit in the decades to come. Indian, Pakistan and other third world countries are their targets, given mounting pressures in the ‘developed world’ for shifting to renewable sources of energy.

During his latest visit, the Saudi prince is reported to have signed several new deals with the Indian PM, including military and defence collaboration. The Saudi monarch expressed interest in investing more than $100 billion in India over the next 2 years, in various fields. We should recall that Narendra Modi’s budget for combating climate change for 5 years was Rs 640 crores, roughly $90 million.

Conclusion

When a nation faced with impending climate catastrophe, instead of entering into emergency damage controlmode, decides to expand business with the same petroleum industry that created the crisis in the first place, while at the same time striking a fatal blow to millions of its forest-dwelling, forest-protecting people with the stroke of a pen, it seems reasonable to conclude that the current government is not going to do anything about the environmental crisis. Our climate agenda has been sabotaged by our political elite, who have chosen to prioritize personal short-term monetary gains over the health and well-being of its citizens. Instead of decisive action and comprehensive overhauls of our energy policy, we are being patronised with pledges, ‘action plans’, jumlas like ‘Swachh Bharat,’ and corporate-funded prizes and awards.

Meanwhile, the Hindu Kush glaciers melt, the Sunderbans drowns, and the insects vanish, posing a major threat to the entire ecosystem. To remain inured to this degradation is to willingly become the boiling frogs in an experiment of our own design.

The author is a political worker and independent journalist.