A war is going on in the field of American education. Is education a fundamental human right, or just another commodity? While virtual reality steps out of science fictions to threaten the world with fundamental changes in the very nature of education, the current state of students, researchers and adjunct professors are no less like dystopian novels.

Dennis Redmond

These days, I feel like a refugee from one of the biggest self-inflicted disasters of modern US history. In some ways, it’s even worse than the frenzy of deregulation which led to the 2008 Wall Street securitization bubble and crash, because its after-effects will last for decades rather than years. This disaster is called the US war on its own public education system.

The most powerful weapons used in this war aren’t bombs and bullets, but buzzwords and boosterism. The war began in the mid-1970s, when the ruling elites of my country, the United States, declared war on the very existence of public education. The point of this war was to convince Americans that education wasn’t a fundamental human right of every citizen, but just another commodity, something you can buy like a cellphone.

Their motivation was simple. A tiny group of billionaires wanted to steal trillions from the American workers who created those trillions. The ideology they invented to justify this theft has many names, ranging from Thatcherism to neoliberalism, but its core belief is the primacy of plutocracy over democracy.

Those billionaires spent a tiny sliver of their fortune to purchase major media outlets as well as the politicians of both US political parties. Cheered on by pro-plutocratic pundits broadcast on this media outlets, these politicians proceeded to slash funding for public primary schools, secondary schools, colleges and universities.

All this had terrible effects on students and on education as a whole. Teacher wages fell like a rock, tuition skyrocketed, students were judged by test scores instead of their ability to think and create, and institutions were judged by the size of their financial endowments rather than the quality of their research.

Today, growing numbers of teachers and citizens are denouncing the damage this war has done to America’s primary and secondary schools, which is a story for a different time. But what I can talk about is what I saw during my five years as an adjunct lecturer in American’s public universities.

From Cold War To Debt Boom

But before I talk about adjuncts, it’s necessary to step back for a second to consider the history of the US educational system. In 1945, the United States became the world hegemon. It produced half of the world’s GDP, it had the world’s most advanced technology, and it deployed the planet’s most powerful military. Part of its vast imperial surplus was used to build and construct one of the most comprehensive systems of higher education on the planet.

This wasn’t due to the generosity of American elites. It was the result of the central class compromise of the Cold War — the Wall Street plutocrats continued to rule, but invested heavily in the military-industrial complex, creating lots of middle-class jobs (annual US military spending averaged about one-tenth of its entire economy between 1950 and 1970). Military funds flowed into universities in order to train the scientists needed to build the latest super-weapons, while the soldiers who had served in the US empire’s incessant wars were given low-cost educational loans.

Community colleges were a crucial part of this story. They delivered high-quality post-secondary education to tens of millions of Americans, many of whom were ex-soldiers, who had never had the chance to go to college before. Even today, decades after the end of the Cold War, many of my students were former members of the military who drew on their veteran’s benefits to help pay for tuition.

The plutocratic war changed this in two ways. First, the public spending on education dropped. The reason is that a consumer debt-financial services complex (a.k.a. Yanis Varoufakis’ financialized Global Minotaur) began to replace the military-industrial complex as the main engine of the US economy. State support for universities and scholarships was cut back, forcing colleges to increase tuition and compelling students to take out loans.Many people still want to believe that America is the land of opportunity, and that if you work hard enough as an adjunct, eventually you'll find a full-time job. But it's just not true.

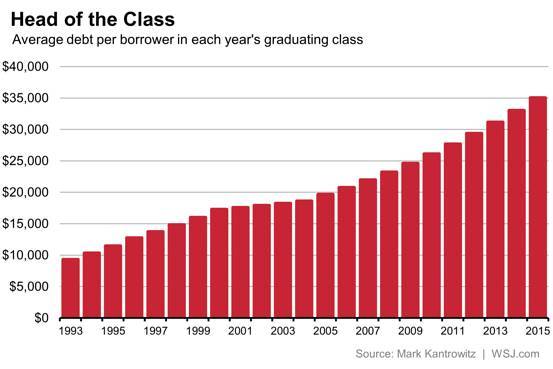

Forty years ago, most US college students graduated with no educational debt. Today, US Federal Reserve statistics show college students owe an astonishing $1.45 trillion, an astonishing 11% of total US consumer debt (for the sake of comparison, the entire US economy produced $18.6 trillion of GDP in 2017). This student loan debt is rising at an exponential rate, tripling in size between 2005 and 2017.

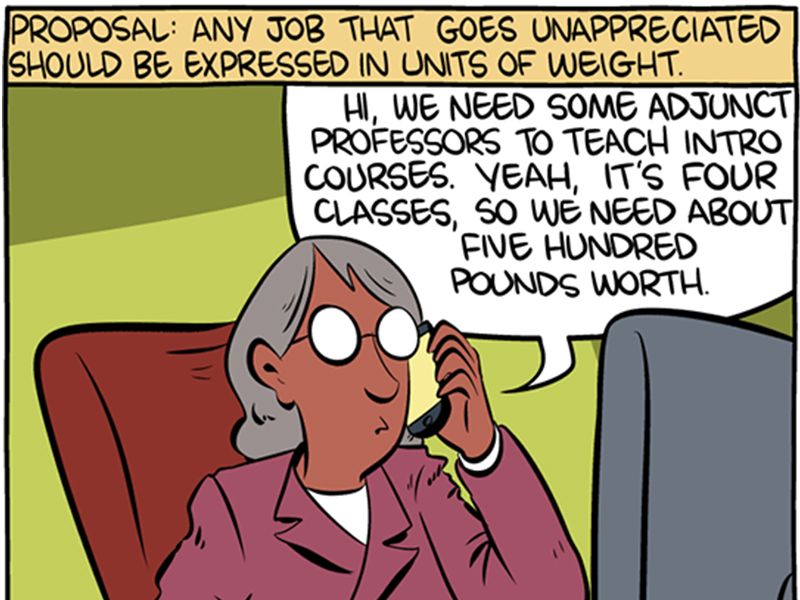

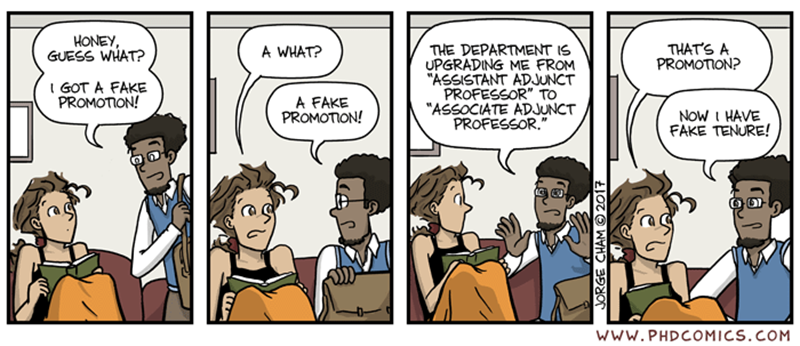

Second, universities cut back on expenses by reducing the number of full-time professors. Back in 1969, most college classes were taught by full-time professors. By 2014, a US Congressional report found three-quarters of all college classes were taught by 1.3 million adjuncts, highly skilled workers with advanced degrees who work for pitifully small wages and no benefits.

This is a story I know well, because I was one of those adjuncts. For five years, I was an adjunct lecturer in America’s public universities. I hugely enjoyed teaching and will be forever grateful for the chance to inspire — as well as learn from — today’s young people, who are amazing in so many ways. But the working conditions of adjunct laborers are straight out of a Hollywood dystopia.

Bodies for Hire

To be an adjunct in America is like being a replicant in Blade Runner. For those who haven’t seen the original 1982 movie or last year’s sequel, Blade Runner is a science fiction franchise about slavery. The films depict a dystopian future where profit-hungry galactic corporations colonize the galaxy by producing genetically-engineered human beings called replicants. These replicants are superworkers with amazing skills, but they are treated as cheap and disposable chattel, because it’s profitable to do so.

Just replace “DNA” with “semester contract”, and you may begin to understand what it’s like to be an American adjunct. We lecturers have degrees from some of the best universities in the world — half of all adjuncts have PhDs and a third have MAs, making us one of the most skilled workforces on the planet. Yet we teach classes for $12 to $15 per hour, a fraction of what full-time faculty make. We receive no sick leave, no dental insurance, no medical insurance and no pension. We work at these jobs because there are literally no other teaching jobs available.

Our wages are the equivalent of 800 to 1,000 rupees per hour, which may sound like a lot of money to readers who live in India and other industrializing nations. But America has some of the highest prices in the world. Currently, rice costs about 400 rupees per kilo in major US cities, compared to 15 to 20 rupees per kilo in India; a US smartphone costs a minimum of 4,000 rupees/month, whereas the same smartphone can be recharged for 199 rupees/month in India; and rent for a US flat averages a colossal 44,000 to 60,000 rupees/month.

Many people still want to believe that America is the land of opportunity, and that if you work hard enough as an adjunct, eventually you’ll find a full-time job. But it’s just not true. Over the past four decades, the pool of qualified teachers has expanded, while the number of full-time positions has been shrinking. Even worse, if you aren’t one of the lucky few hired during the first two years after you earn your PhD, your chances of getting a full-time job drop to zero.

There are two main reasons for this. First, adjuncts spend all their time teaching and are given no research support, making it almost impossible to keep up with the latest developments in their field. But even if you somehow maintain your productivity as a scholar, you will run headlong into one of the most vicious aspects of US academia, the dirty secret all academics know about, but rarely discuss.

How the Authoritarian Kleptocracy Rules

This is the fact that US academia is an authoritarian kleptocracy. This kleptocracy runs much deeper than the structural forms of oppression at work in US society, namely racism, sexism, homophobia, class privilege, etc. In fact, it would be a fatal mistake to assume that the academic kleptocracy could be overthrown by just getting rid of these latter inequalities, i.e. that hiring more women and faculty of color would magically solve the problem. The reason is that structural unfairness isn’t a bug in our system of plutocratic misrule. Rather, it is is most constitutive feature.

It’s a painful irony of history that the Far Right revanchists understood the nature of this kleptocracy far better than the academics themselves. If you listen to the revanchists denounce public universities, you will hear the same Big Lie repeated over and over again: supposedly, all professors are “out-of-touch liberals”, all students are “lazy kids who party all day”, and all college degrees are “useless paper”. These are despicable lies, but we should ask ourselves why tens of millions of Americans find these lies to be convincing. They are convincing precisely because the rhetorical framework of the lie contains a nugget of truth: it accuses the US academic system of being an elitist kleptocracy — which it indeed is.

Ivy-League Institutions

Personally, I never understood just how entrenched this kleptocracy was until I became an adjunct. While there are a lot of moving parts to the system, I’ll focus on just one element, namely the process of teacher selection. Here’s how the selection system works: the newest university graduates with degrees from Ivy League institutions are the first to be hired as professors. This isn’t because they’re the smartest folks around, but because they come from obscenely wealthy institutions with well-funded brand names. This obscene wealth also encourages structural nepotism in academic hiring and promotion. Well-heeled, expensive mediocrities with lengthy resumes get hired instead of hard-working, innovative thinkers.

The next to be hired are the newest graduates from the top-tier state schools, who are as a rule far more competent than their Ivy League peers, but don’t have the power of an Ivy brand name to back them up. Last to be hired are the newest graduates from the non-Ivy League private schools or lower-tier state schools, who are also more competent than most Ivy Leaguers, but have even less name recognition than the major state schools.

Adjuncts are the lowest tier of this kleptocracy. They are where the vast majority of all new graduates — including increasing numbers of Ivy Leaguers themselves, because not even that Yale degree guarantees that you will get a job anymore — end up. If you’re still an adjunct during your third year after graduation, most hiring committees will toss your application for a full-time position in the trash.

Given these hiring practices, the slow-motion implosion of US academia suddenly makes sense. The Ivy Leagues will tend to produce elite-level discourses consumed by nobody but a few elite think-tanks. The state schools will produce more general and useful forms of knowledge, but will be constantly hampered by the lack of resources available to the Ivies to disseminate their work (e.g. the state-school academic presses were among the first institutions to be gutted by the plutocrats). Over time, the result is the phenomenon of the “theory ghetto” — small networks of scholars working on esoteric projects in obscure journals, without any connection to larger social struggles. Finally, the adjuncts who do most of the teaching are structurally blocked from accessing the circuits of knowledge-production, through overwork and lack of local resources (community college libraries are underfunded, research support is zero).

Virtual Reality and the Digital Commons

I said earlier in this essay that Blade Runner is about us adjuncts, but I left out one other crucial detail. This is the fact that adjuncts, like replicants, are being hunted by by one of the most powerful productive forces of 21st century capitalism: the field of interactive media.

There is a real possibility that within five years, significant numbers of us 1.3 million adjuncts — followed shortly thereafter by most full-time professors — will be fired. There will still be universities and students, but the teachers will no longer be located in the United States.

You may have heard stories about the latest developments in artificial intelligence, everywhere from self-walking robots to self-driving cars. While robots aren’t going to replace teachers any time soon, there is a major media revolution occurring which will fundamentally change the nature of education in the 21st century.

This revolution is the spread of virtual reality (VR) platforms, which generate remarkably immersive experiences of virtual world for the price of a laptop computer ($600 or less). VR is already beginning to change videogames and other forms of interactive media. However, it will have a truly seismic impact on the profession of teaching.

Within two or three years, it will be possible for a teacher to don a VR headset and interact in a virtual classroom with VR-equipped students from all over the world. In effect, VR will fuse the physical experience of classroom interaction with the flexibility of online learning platforms such as Google Classroom and Canvas. Just as projectors supplanted chalkboards in universities around the world, VR learning environments will begin to supplant physical classrooms.

You may have heard stories about the latest developments in artificial intelligence, everywhere from self-walking robots to self-driving cars. While robots aren't going to replace teachers any time soon, there is a major media revolution occurring which will fundamentally change the nature of education in the 21st century.

VR has the potential to unleash amazing new forms of long-distance education and new types of collective learning. However, it all depends on who controls this new technology. If the plutocrats get their way, all 1.3 million US-based adjuncts — followed in due course by most full-time US professors — will be replaced by highly-skilled professors either fluent in English (or utilizing AI-run digital translation software) from all over the world, who can work for 70 rupees an hour instead of the 4000 per hour Americans get.

That said, there are also reasons to be hopeful. There’s another side of the VR revolution, a story that the Blade Runner films, because they are politically reactionary Hollywood blockbusters meant to sell tickets and dissuade us workers from rebelling against our masters, are not interesting in telling.

This is the story of the immense potential of the digital commons. In the next essay, I’m going to talk about some of the ways young Americans have been creating their own digital networks, and fighting back against the plutocratic war on education.

__________________

Note

[i] In Florida, where I worked as an adjunct for four years, adjuncts do not qualify for Social Security. The funds normally deducted for Social Security are routed into a retirement fund, which sounds fair, but isn’t, because nobody gets Social Security benefits without paying a minimum amount into the fund at the beginning of their career. Because of the years I spent getting my multiple advanced degrees, I do not qualify for Social Security, and in all likelihood never will. I will literally have to work until the day I die.

[ii] It’s worth mentioning that something similar will begin to happen to other high-wage First World service professions which involve face-to-face interaction rather than the delivery or handling of physical commodities, e.g. accountants, legal professionals, therapists, advertisers, and medical diagnosticians.